Rachel Whitney, Curator, Sapulpa Historical Museum

Kim Shockley, Volunteer, Sapulpa Historical Museum

This week in Sapulpa history, Elizabeth Estelle Alliston was born to Sallie Elizabeth Alliston in Rankin County, Mississippi on December 18, 1880.

Sallie Alliston was married to Robert Ruci on May 15th, 1869. Sallie was listed in the 1880 Census as “white,” whereas Robert was not listed at all. Robert was more than likely an Albanian immigrant or of Albanian descent. Sallie had three children, Elizabeth, John, and Benjamin. It is unknown if Robert is their father.

The three children were listed in the Census with slight variations in ethnicity: “Freedman,” “Free Negroes,” or “Mulattoes.”

It is also unknown what Sallie’s economic status was during this time after the Civil War. The town of Brandon, the county seat in Rankin, MS, was a town with less than 1,000 people.

The early years: Brandon, Mississippi

“During the Civil War, Brandon felt the full wrath of the Union Army under the command of General Sherman as it marched through Jackson to Vicksburg. Most of the town was burned by the Union soldiers. At the center of Brandon stands a monument of a Confederate soldier placed there in 1907 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The site of the monument is believed to be where General Sherman had his soldiers stack arms while they occupied the town.

“There were bouts of massive yellow fever epidemics during reconstruction years (1871, 1878, 1888, 1893). In 1878 was the worst of it hit, and many schools and churches closed. Brave citizens continued to rebuild and educate their children as the 19th century ended. Streetlights were installed in 1911, and, in 1917, the City of Brandon allocated a $5,000 bond issue at 6% interest for paving streets.

“Tragedy struck again, in November of 1924, when a fire destroyed most of downtown Brandon, including the courthouse. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, times were hard in the entire country. Residents of Brandon, as well as of Rankin County, did not feel the hunger as desperately as others, because it was an agrarian society and the rich farmland provided enough for the local population to survive.”

After finishing high school, Elizabeth “taught in the public schools of her community for a number of years.”

Just after her 16th birthday, Elizabeth was married on January 21, 1897 to Augustus G. McCoy in Brandon, MS. Within a year or two, the McCoy family left Mississippi for Tennessee.

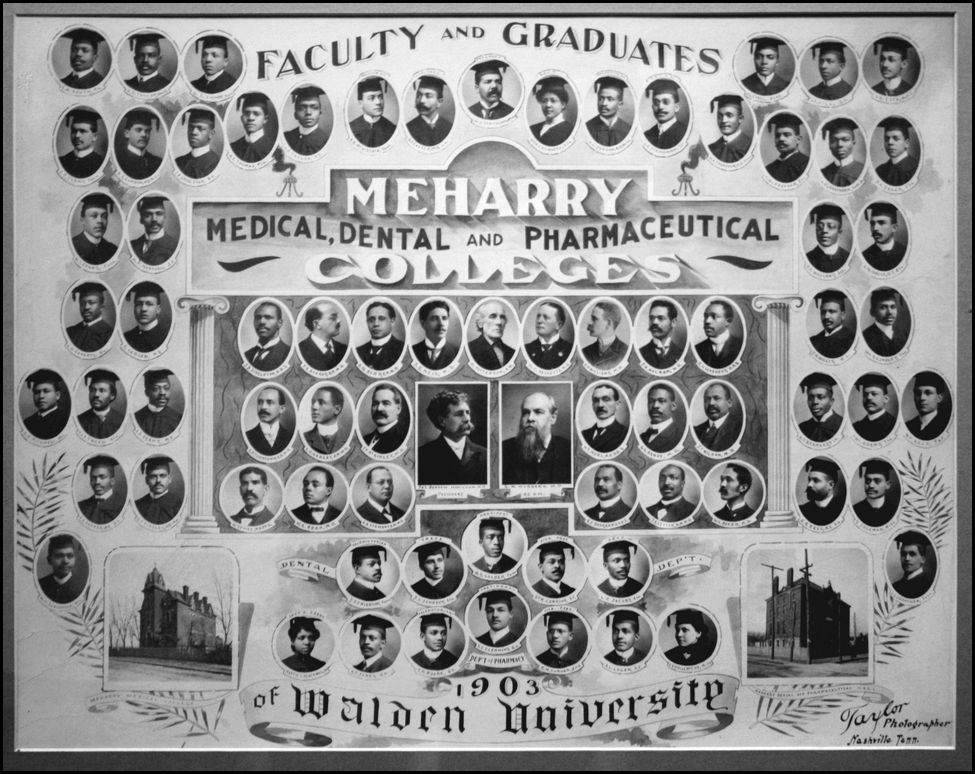

Augustus was listed as a sophomore at Meharry Medical College, Walden University in the 1900-1901 school year. Elizabeth was listed as a freshman that year.

Meharry Medical College

“In the 1820s, 16-year-old Samuel Meharry was hauling a load of salt through Kentucky when his wagon slid off the road into a muddy ditch. With rain and nightfall limiting his options, Samuel searched for help. He saw a modest cabin that was home to a black family recently freed from slavery. The family, still vulnerable to slave hunters paid to return freedmen to bondage, risked their freedom to give Meharry food and shelter for the night.

“At morning’s light, they helped lift the wagon from the mud and Meharry continued his journey. The black family’s act of kindness touched young Meharry so deeply that he vowed to repay it. I have no money now, he said as he departed, but, when I am able, I shall do something for your race. Tragically, history never recorded the name of the courageous black family, and perhaps their identity even receded in the mind of Samuel Meharry as he grew prosperous in the years that followed.

“Even so, 40 years later, as the Civil War ended and black citizens began their long struggle for rights guaranteed by the Constitution, Meharry seized an opportunity to redeem his vow. When leading Methodist clergymen and laymen organized the Freedmen’s Aid Society in August 1866, to elevate former slaves, intellectually and morally, Meharry acted. He and his four brothers Alexander, David, Hugh and Jesse, pledged their support to Central Tennessee College’s emerging medical education program. With $30,000 in cash and real property, the Meharry brothers repaid the black family’s Act of Kindness with one of their own. In 1876, they funded the College’s Medical Department, which evolved over time into what we now know as Meharry Medical College.”

In two years, Elizabeth McCoy graduated with a pharmacy degree in 1903. She was listed among the few graduates for the Class of 1903 in the pharmaceutical degree. “She took charge of a drug store and studied and finished medicine, organizing the East Side Infirmary, remaining in charge of said institution for nearly eight years. She held many creditable positions in keeping with her ability and profession, being Assistant Instructor in Meharry Medical College and also a teacher in Mercy Hospital for a short time.”

Augustus and Elizabeth welcomed three children to the world. While going to school, the pair raised their children: Eva McCoy, born December 27, 1897, a son born and died October 17, 1899, and Katye McCoy born February 28, 1901.*

*Note: A death record for an infant McCoy: black male, age zero, born and died 17 October 1899 in Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee. The child’s address was listed as 416 Fern Street, with the father unnamed but having been born in Mississippi, and the mother listed as Elizabeth McCoy, born in Mississippi. The child was not named and was shown as buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Nashville, TN.

Dr. Elizabeth McCoy and Dr. A.G. McCoy were granted divorce in July 1905 in Knoxville, TN. Dr. Augustus G. McCoy moved to Arkansas and died in 1924.*

*Note: the 1910 and 1920 Census records for Crittenden County, Arkansas showed Dr. A.G. McCoy was a “widower.” However, his death certificate in 1924 listed his marital status as divorced.

Dr. Elizabeth McCoy continued her education in Knoxville, graduating from Knoxville Medical College in 1908. Elizabeth was among the first and last graduating students from Knoxville Medical College.

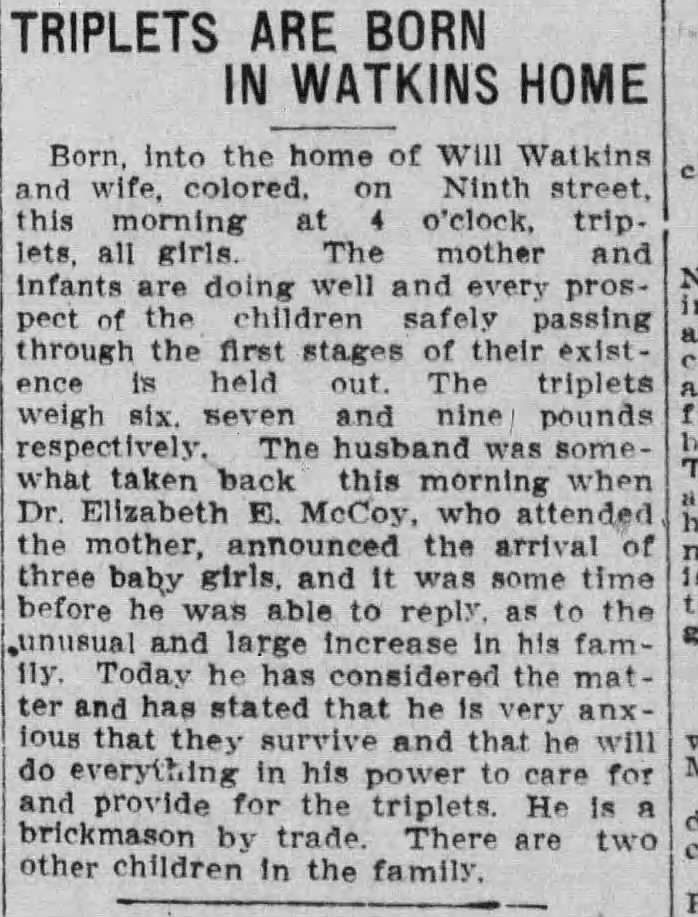

McCoy Delivers Triplets

“After the closure of the medical department at Knoxville College in 1900, Knoxville Medical College was organized as a replacement facility that opened on December 6, 1900 by the City of Knoxville. At the time of its opening, the only other Black medical school in the state was Meharry Medical College in Nashville. In January 1909, the school was visited by Abraham Flexner who authored the critical Flexner Report (1910) about the state of medical education. By 1910, Knoxville Medical College was forced to close, most likely due to the poor educational conditions and its reputation for ‘mediocrity’ in its training. The college had graduated 21 students in the 10 years of operations. After the closure of Knoxville Medical College, Lincoln Memorial University bought the college in 1910.”

Elizabeth took her Tennessee State Medical Exam in May 1908. And the following year, she applied for her physician’s license in Knoxville, June 1909.

One of her first recognitions in the medical world was within her first month after her license, she successfully delivered triplet girls. “Born into the home of Will Watkins and wife, colored…this morning at 4 o’clock, triplets, all girls…The husband was somewhat taken back this morning when Dr. Elizabeth E. McCoy, who attended the mother, announced the arrival of three baby girls, and it was some time before he was able to reply as to the unusual and large increase in his family. Today he has considered the matter and has stated that he is very anxious that they survive and that he will do everything in his power to care for and provide for the triplets. He is a brick mason by trade. There are two other children in the family.”

Dr. Elizabeth McCoy was found in the 1910 Census for Knox County, TN. She was a physician and was listed as “single.” At her home, it was listed that at least two others were living in the home: Sadie Browder, a nurse, and Erskin D. Johnson, a medical student.* Erskin Johnson was born in Jackson, MS on June 20, 1887. He took his Tennessee Medical Exam in June 1912.

*Note: Eva and Katye McCoy were not listed on the 1910 Census record, however.

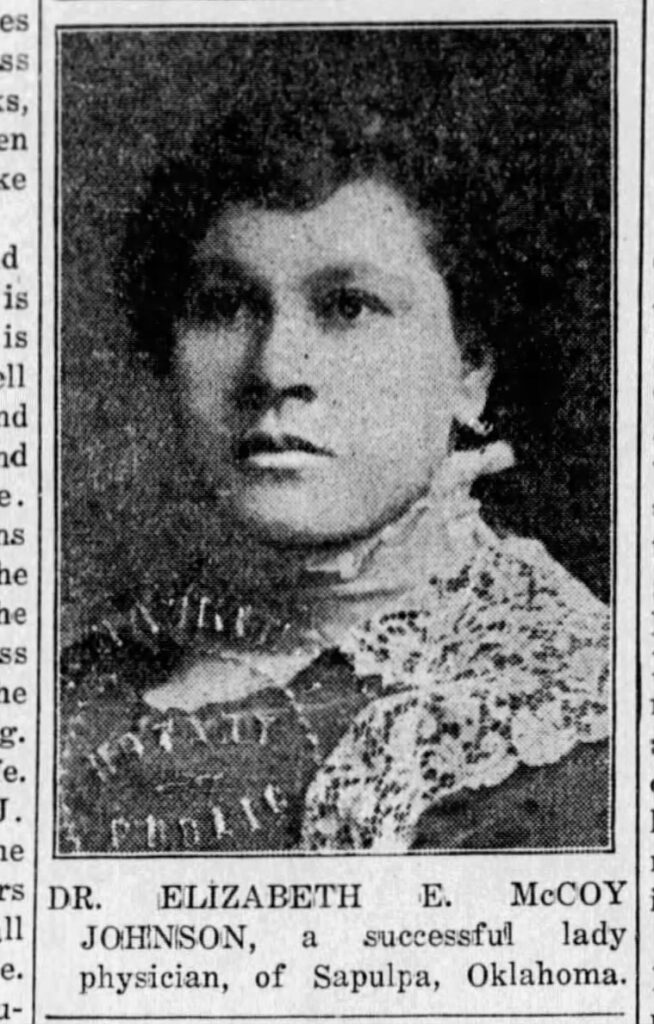

It is not known if Dr. Elizabeth McCoy and Dr. Erskin Johnson were legally married, but a handful of documents and articles mention Elizabeth as: “Mrs. Dr. McCoy,” “Dr. McCoy-Johnson,” or “Dr. E.E. Johnson.” However, most documents and articles name her “Dr. Elizabeth McCoy.”

Moving to Sapulpa

For reasons unknown, Drs. Elizabeth and Erskin moved to Sapulpa In 1913. Dr. Elizabeth McCoy Johnson is listed in the 1914 Sapulpa City Directory as residing at 319 Johnson (the address is also listed as 419 Johnson).

Dr. Erskine Johnson’s military draft card (1917) stated he was a physician and married, even though it did not list his wife’s name. However, the address, 419 W. Johnson was the one registered to Dr. Elizabeth McCoy. He also received a draft card during WWII. It is not known if Dr. Johnson was called to serve in the military.

The 1918 Sapulpa Directory listed both Elizabeth McCoy Johnson and Erskin D. Johnson, physicians, living at 419 Johnson. Elizabeth lived and worked out of the home address, while Erskine worked at 515 E. Hobson.

During the 1918 year, a divorce must have taken place; in August of that year, Dr. Erskine D. Johnson applied to practice medicine in St. Louis, Missouri. By 1920, Dr. Johnson had applied for a marriage license in St. Louis, and by 1942, he was living and practicing medicine there. He was found again in the 1950 Census for Missouri, where he was listed as a school doctor. Dr. Johnson remained in St. Louis for the remainder of his career, and died on March 14, 1964, at the age of 76.

Both daughters came with Dr. Elizabeth McCoy to live in Sapulpa in 1913. Eva would have been nearly 17, and Katye would have been nearly 13 years old.

Eva McCoy is listed as a teacher from 1914. It is possible she was a teacher at Booker T. Washington in Sapulpa. Katye was first listed in 1920 as a student. It is unknown where she received her education, however, it is possible either Eva and Katye joined the Oklahoma Baptist College, just blocks away from Booker T. Washington.

In the summer of 1917, a search for Dr. McCoy’s vehicle was added to the newspaper. “A Ford roadster was stolen on Wednesday night from Dr. McCoy’s private garage. The doctor’s name was painted on the right side.” Dr. McCoy also put an ad in the newspaper for a reward of $25 for the “recovery of car and arrest of thief.” About 3 weeks later, it was announced that someone was charged in the theft of the vehicle.

According to a February 2, 1918 article in The Tulsa Star newspaper, Dr. Elizabeth McCoy Johnson was reported to have been ill for the past two weeks due to nervous strain brought on by overwork. The story listed her extensive practice and extra time devoted to Red Cross work. Her strain may have also been due to domestic issues, as this was around the time Dr. Johnson left.

By the summer of 1918, Creek County Red Cross listed many workers for the districts’ women in the organization. “All of the members of the board with but two exceptions, were in attendance at the meeting also the following representatives, Mrs. B.C. Kinnaird, Bristow, Mrs. College, Oilton, Mrs. W.S. Cole, Kiefer, Mrs. H.P. Newton, Shamrock, Dr. McCoy Johnson, representing the colored auxiliary, and Mrs. J.W. Hoover, the Sapulpa chapter.”

“The colored Red Cross auxiliary held quite an enthusiastic meeting Tuesday night and a nice amount of money from the big drive was turned over to Dr. McCoy, chairman.”

From the Black Dispatch, October 11, 1918: “Dr. Elizabeth McCoy Johnson , who has erected at Sapulpa, a handsome two-story brick structure. Dr. McCoy-Johnson began business in the oil city with a capital of thirty cents and is an example of the womanhood of the state of what one woman, unaided, by thrift, economy, and skill, has accomplished. The state should be proud of this progressive Negro woman.”

In 1920, Dr. McCoy aided in helping an injured officer from Edna, Oklahoma. Four men were arrested for “assault with intent to kill of Willie Carol, negro constable of Edna. This assault occurred several weeks ago at a picnic at Edna when Carol was acting as officer of the day. A negro man was disturbing the peace and the constable had ordered him to be quiet when somebody slipped up behind him and struck him over the head with a club. He was not found until the next morning. He was brought to Sapulpa where he was given treatment by Dr. Elizabeth McCoy.”

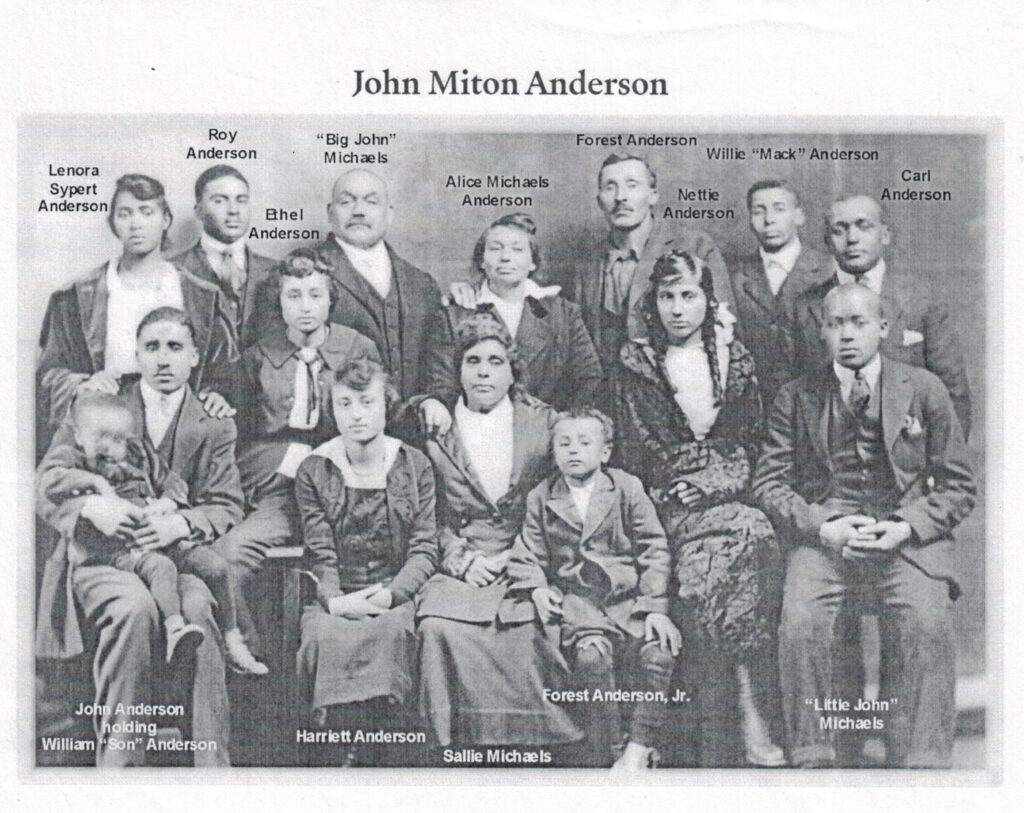

The trio of McCoys lived at 403 Johnson by 1920. As early as 1921, the two daughters were listed as teachers. In 1924, Katye was listed as the only teacher found at East Side School. In 1926, the Sapulpa City Directories also listed Hayden Carter, who worked at Schram Glass, and Roy Anderson, a laborer for the Frisco Railroad. These men would become the husbands of Eva (McCoy) Carter and Katye (McCoy) Anderson.

Dr. McCoy “not only succeeded as a physician and surgeon, but was a financial success, acquiring property and erecting a beautiful brick building to be used as an office and store purposes on some of her Sapulpa property.”

In 1914, Dr. McCoy purchased Lot 12, Block 1 in Businessmen’s Addition to the City of Sapulpa. In January 1915, she also purchased the West 16 feet of the East Half of Lot 13, Block 1 in Businessmen’s Addition. This property served as both her residence and medical practice.

Dr. Elizabeth Estelle McCoy passed away on April 21, 1928, after struggling with illness for a few weeks. She is buried in Fairview Cemetery on the northwest side of Sapulpa.

“The death of Dr. Elizabeth McCoy, a prominent physician of Sapulpa, Oklahoma, recently, marks the passing of a woman high in the ranks of the medical profession, and one of whom all Oklahomans in every section were proud.”

The headline of her obituary in the Black Dispatch labels her as “Oklahoma’s Only Woman Doctor.”*

*Note: It is not known for certain if she was the first or the only physician in Oklahoma. The Tulsa Star had mentioned in 1914 when Dr. McCoy moved to Oklahoma stated: “Mrs. Dr. McCoy the lady Physician is doing quite a deal of practice now. We are proud to note that we are one of few cities in the state who have a lady physician.”

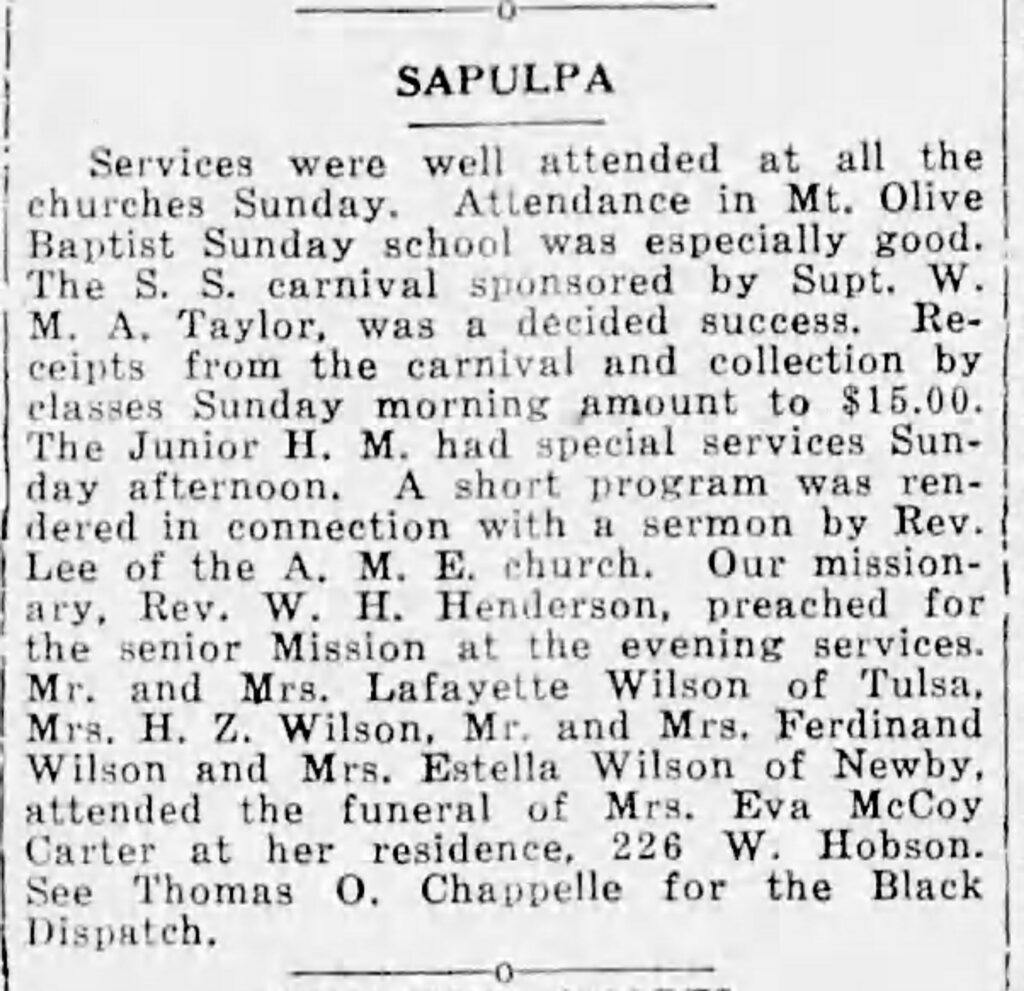

Just two short years after Dr. McCoy’s death, Eva Carter passed away. Hayden Carter had just lost his mother in May 1930. In late June, Hayden Carter had to say goodbye to his wife. Creasie Carter, Hayden’s mother, and Eva Carter are buried in Fairview Cemetery. They are buried near Dr. Elizabeth McCoy’s grave. Hayden Carter moved to Iowa after their deaths. He remarried in 1933 and passed away in 1972.

It is unknown on the timeline of when Roy and Katye Anderson moved out of Sapulpa. There are listings of the couple living in Earlsboro, Oklahoma at the time of Dr. McCoy’s death. However, it is also known they owned land in Sapulpa. The Andersons are listed in Sapulpa’s City Directory from 1930 to 1934 living at 410 E Hobson. Based on the 1940 and 1950 Census the Andersons lived in Seminole County.

In 1955, Roy and Katye Anderson were found in San Jose, California. Royal “Roy” Anderson died in 1967 and is buried in Earlsboro, OK.

Katye continued teaching her whole life. In 1962, Katye Anderson, “a widow,” executed a warranty deed in favor of L.A. Hudgins for Lot 12, Block 1, Business Men’s Addition to the City of Sapulpa. Her signature was notarized by Lon T. Jackson of Sapulpa, Oklahoma. However, the county was listed as Payne County, and not Creek County. Katye sold land to the Turnpike Authority in 1951. A few years later, it was sold back to her in 1955.

Katye Anderson passed away in September of 1980 and is buried in San Jose, CA.

(Tulsa Star, September 19, 1914, February 2, 1918, April 17, 1920; Sapulpa Herald, March 27, 1917, June 14, 1917, June 18, 1917, July 6, 1917, July 7, 1917, January 8, 1918, May 24, 1918, May 29, 1918, August 20, 1918, February 4, 1920, July 13, 1920, August 5, 1920, April 23, 1928; Black Dispatch, September 21, 1917, October 11, 1918, May 18, 1922, May 17, 1928, July 3, 1930; Creek County Republican, October 10, 1919; Tennessean, October 22, 1899, September 9, 1911, June 11, 1912; St Louis Globe-Democrat, August 15, 1918, April 30, 1920; Nashville Banner, May 14, 1898, May 26, 1898, October 8, 1904, July 8, 1912; Knoxville Sentinel, May 5, 1908, June 30, 1909, July 27, 1909; Journal and Tribune, July 13, 1905, July 25, 1905, July 1, 1909; FindAGrave.com; Wikipedia; FamilySearch.com; History of Brandon; Meharry Medical College; Ancestry.com; Sapulpa City Directory)

Author’s Note: I wish to give a special thanks to Kim Shockley who has joined the Sapulpa Historical Society by volunteering with us; she has been taking the lead on this research project. In addition, I wish to thank Hattie Knox for dedicating much of her time researching Black History of Sapulpa. Furthermore, I wish to give a shout out to Dr. Shelly Martin Young for bringing the research to light.