By Don Diehl

His is called “the Greatest Generation” for good reason. Sapulpa resident Paul Morgan, who turns 90 on August 27, was 18 and a high school student from Ames, Okla. when Uncle Sam called in 1943.

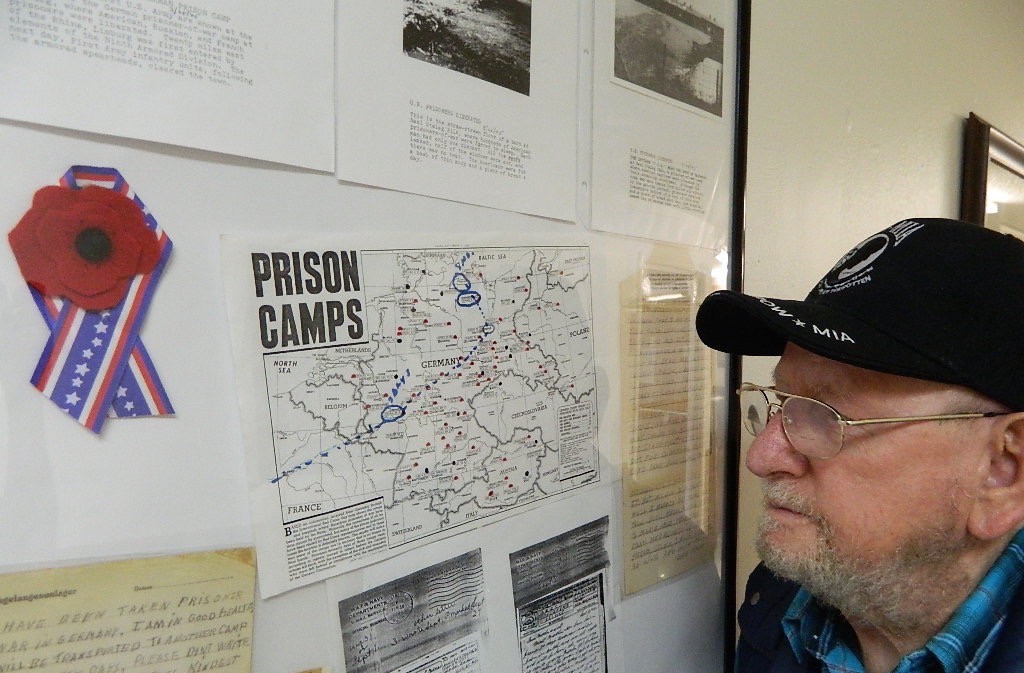

A year later he would be in Stalag 12A, one of Germany’s largest Prisoner of War camps, Rawstock, Germany.

His is a story he didn’t talk much about until recent years. Then he realized he must — not so much for him but for new generations who need to know.

Much of Morgan’s story is told in a recent video-taped interview at his residence in Arbor Village in Sapulpa where he is glad to receive visitors. On both sides of his door to his room are big frames displaying pictures, maps and other memorabilia of the era and time he spent in the infantry and then in the German POW camp, along with some keepsakes from some of the kids Morgan has visited at their schools to tell his story.

Morgan was born and reared on a farm west of Ames, Okla., the second of three sons. It wasn’t the best of times. The family raised a few chickens and if meat hanging on the back porch through mid-winter got scarce, the boys could hunt and fish — something Paul loved to do. They could jump up some jackrabbits on Booger Island where the Cimarron River split going south.

“I remember eating some jackrabbit burgers,” he said laughing, “and ‘possum was good cooked over an open flame.”

There, he also noodled for some of the big catfish. And despite the Dustbowl days, there were still quail in that area of the state.

“We would have big quail fries” after a end of season harvest, he said. He remembers one year, his mom canning more than 500 quarts of produce.

Such was life growing up — sometimes hard. But nothing compared to what it would be after being captured by the Germans and moved from camp to camp — sometimes marched and finally hauled in cramped box cars minus food and water.

Qfter being drafted, Morgan went first to Lawton then to training camp in Florida, Morgan and his outfit would eventually ship out of Ft. Campbell N.J.

“We boarded ships and waved goodbye to the Statue of Liberty,” Morgan said, “knowing we wouldn’t see her again until after the war” if they came back alive.

The crossing in a 15-ship convoy kept them on the water 15 days before docking at Liverpool, England on June 5, 1944, the day before D-Day on June 6. A week later, in what is called D-Day, plus 6 Morgan would be among the replacements for those killed or wounded in the initial Normandy invasion.

German casualties on D-Day were around 1,000 men. Allied casualties were at least 10,000, with 4,414 confirmed dead.

“They were burying the dead of the past six days when we got there,” said Morgan. “The Allies had the Germans pushed back when we joined the outfit but we still had snipers to weed out all through France on the way to Germany.”

The Germans for the most part had pulled back to the Sigfried Line. That campaign, history would record, was one of the most frustrating and bloody series of battles fought by the U.S. Army in Northwest Europe during World War II.

In order to break through the German-Belgian border north of the Ardennes and eventually reach the Rhine, the First and Ninth divisions of the U.S. Army dispersed themselves along the Line. This is where Morgan, set to become a corporal and having survived fierce fighting, was captured.

Coming out of Normandy, Morgan’s outfit faced the local terrain, called Bocage in French — farmland separated by thick coastal hedgerows. The hedgerows are dense and high. Allied tanks would expose thin belly plates to German defenses when going over the hedges.

Morgan said that flamethrowers proved effective, and he and other soldiers could sit on the tanks and throw explosives at the enemy once past the hedge where they were holding out.

The operation gained a foothold.

But there were counter attacks. Morgan and a another soldier first escaped German troops as it overrun the advancing Americans.

“We were wore out from fighting and running,” Morgan recalls. “We were separated from our outfit”

The two split open a shock in the farmland and waited for daybreak to try and return to their group. Instead, they ran right into the German contingent and were forced to surrender. Another two dozen also had been taken captive of the Germans.

There was little food for the prisoners and at times Morgan and others doubted they would survive the POW camp let alone the war.

He tells of one day, however, that survival took on a real meaning. The POWs had decided they would refuse to work until they were fed properly. The food in the camp consisted of thin cabbage and potato soup two times a day and stained water they called coffee.

A “mean little captain” was in charge of the camp. He allowed the prisoners to lay out until 10 a.m. Then the order came. Roused out of bunks and at attention, the captain told his soldier guards to begin shooting any of the prisoners who had not reported to work in five minutes.

“The Geneva Convention” meant little to the guards and their captain. Morgan said everyone chose to go to work.

Morgan and the other 24 captors from his outfit were liberated on May 8, 1945 as Russian tanks arrived.

Thankful to be alive, the men were fed and doctored in France and on their way back to America.

Back at home Morgan met and married a telephone operator. Barbara died in March of 2010. They had been married 63 years and eight months. Two of their seven children are deceased. He has 14 grandchildren. 10 great and one great-great grandchild. Nearby, his oldest daughter lives in Tulsa.

After returning home, Morgan started farming and then building. In 1989 the Morgans had a home on their son’s place in Prue but moved to Tulsa area when his son died.

Today he enjoys Arbor Village. He has had some health problems — has had a heart bypass — but likes visiting and recounting his war experience.

A few years ago Paul and Barbara Morgan took four months off and looked up all of his old buddies from his outfit he fought alongside and survived the POW camp. It was the first time in 50 years they had seen one another. They had made a habit of corresponding every Christmas. Today besides Morgan, there are four of the soldiers left.

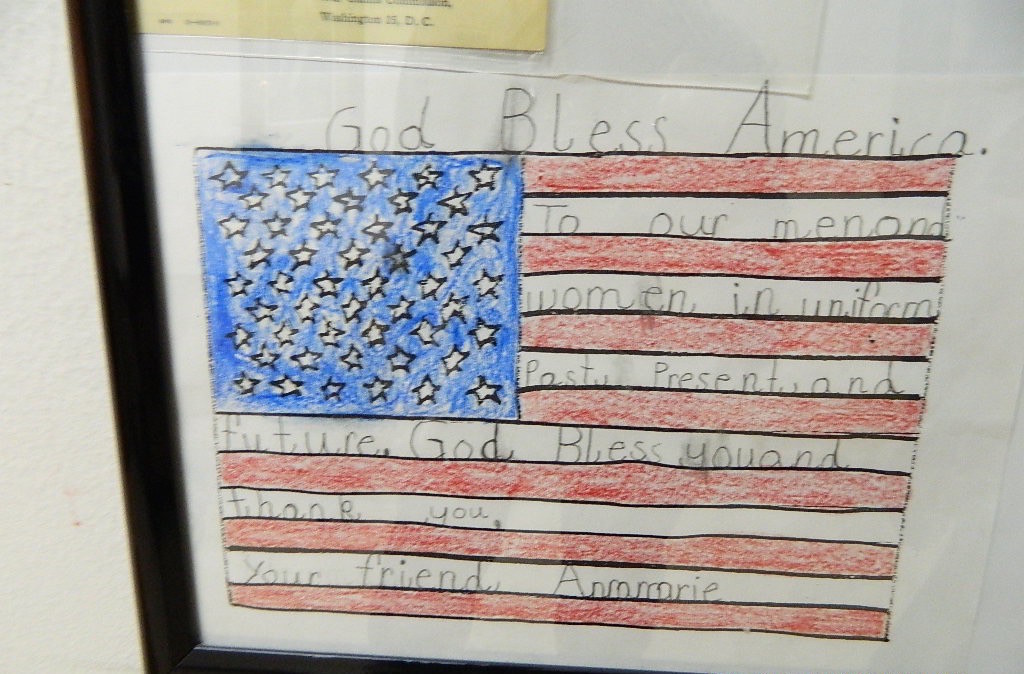

Over the past several years, Morgan also has made himself available to speak in schools, churches and other meetings. Some of the students have written special thank yous. Those are among the keepsakes on his wall.

And in his mind a peace in knowing he did what he had to do.