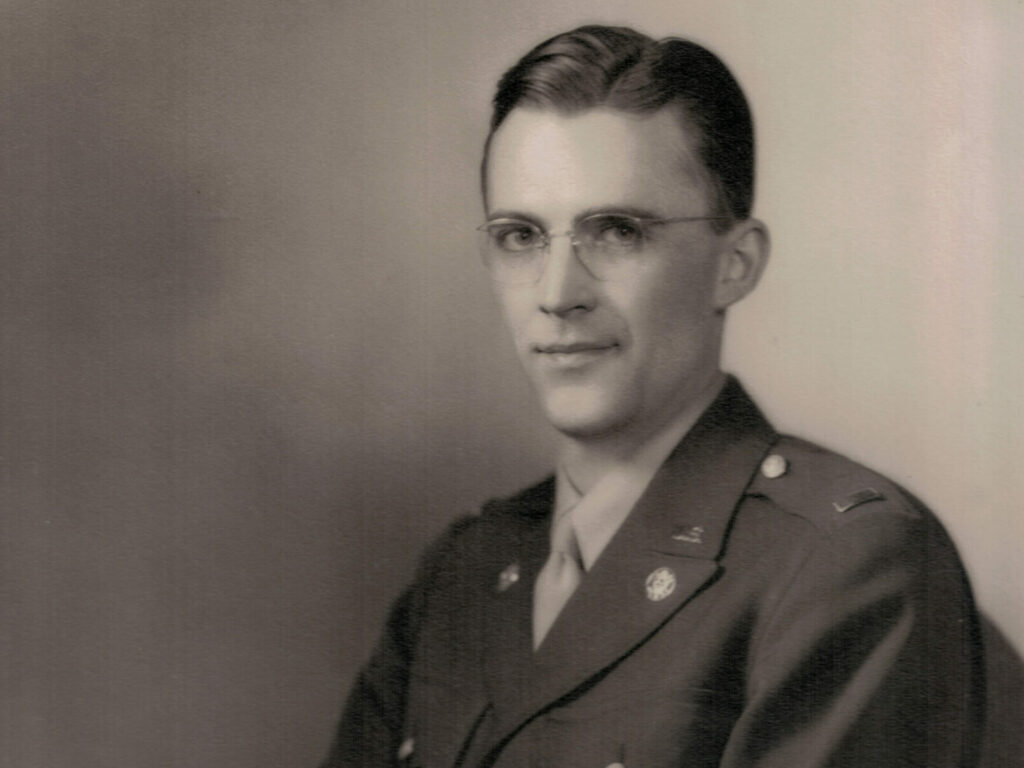

Thomas L. Blakemore may be one of the most important men from Sapulpa that you’ve never heard of. The man’s career spanned decades, continents, and a world war, and his imprint on the world is probably one of the most prominent of any of our fellow Sapulpans. And yet, despite his notoriety in certain circles and around the world, most of our neighbors wouldn’t be able to name the man nor what he did that was of any significance. That needs to change.

Born in 1915 to Thomas and Ernestine Blakemore, both of whom were attorneys, Thomas L. Blakemore seemed to have been destined to become an attorney himself, which he did, first graduating from OU, and then attending Cambridge University on a scholarship. The scholarship was sponsored by the Institute of World Affairs and had a condition attached— the recipient must study the Japanese constitution and law after studying in England.

To Japan

Japan before World War II was a much different country than modern Japan. Many of the Japanese natives were destitute and the economic system of the country was in shambles. Foreigners like Blakemore who were interested in Japanese law were few and far between, and Blakemore himself was hesitant, believing it might ruin his legal career. Still, he decided to go for it, hoping that his knowledge of Japan might prove useful in the future. He had no idea how right he would be.

After completing his studies at Cambridge University, Blakemore entered the Law Department of Tokyo University. It was 1939—just two years before the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States.

As tensions in Japan mounted, the American Consulate called Blakemore and ordered him to return to the United States, but he procrastinated, not wanting to ruin his studies. Eventually, he realized that if he were caught in Japan after war broke out, he’d be arrested or worse.

Returning home

When he finally made the decision to return home, it was too late; the deadline for leaving the country had long since passed. His only chance was to board a ship bound for Shanghai. He initially tried to secure space on one ship but found there was no space available. His mentor at Tokyo Imperial University came to his rescue, securing him a spot on a shipping vessel bound for Shanghai. Once he arrived, Blakemore then snuck onto the last American ship bound for Hawaii.

Thomas Blakemore’s ship arrived in Hawaii on a day that lives on in infamy: December 7th, 1941. Blakemore witnessed the attack on Pearl Harbor firsthand, though there’s little record of what he saw. One account says “as soon as they passed over a bridge, it began to collapse into a deep ravine.”

Though the details about his time in Hawaii are sparse, it’s clear there was no time to relax; Blakemore was summoned by General Donovan to Washington D.C. almost immediately, and soon sent him to China, where he served as a captain in the U.S. Army and was put in charge of collecting information on Japanese military covering India, China, and the States for a new department called the “Information Control Office,” which would later become the CIA. During this time, Japan was steadily driven to defeat.

Back to Japan

Blakemore, who had barely escaped Japan in one piece, was sent back to a war-torn Tokyo in late August of 1945. His eyes scanned the endless stretch of burnt ruins and he was given his new assignment: it was time to dismantle and completely rewrite Japan’s constitution under new democratic principles. Blakemore had just celebrated his 30th birthday and his team literally held the direction of the future of all of Japan in their hands.

By the following May, in 1946, Blakemore was assisting General MacArthur in restoring the Japanese economy. Blakemore, along with other lawyers and servicemen, worked to abolish the traditional Japanese dictatorship of the emperor and reconstruct the country under a new, more democratic order. Blakemore himself knew his own worth in the cause. “I was the only person who had actually studied the Japanese law,” he said. “I participated wholeheartedly in the process of establishing a new constitution and law. There was really no one else besides me.”

General MacArthur originally wanted to completely eradicate the presence of the Japanese Emperor. Not in the physical sense, but it in the cultural and political sense. How could a people under a new democracy expect to thrive if they still believe in a divine, god-like emperor that sees himself as above and separate from those he represents?

It was Blakemore who pushed back against MacArthur’s idea to completely remove the presence of the emperor from Japanese culture. “The existence of the emperor is essential to the Japanese,” Blakemore said. But he also recognized that the existence of the emperor as it had been—as the one who was responsible for the war—was not possible. Therefore, the role of the emperor was remade to be more of a figurehead, who had to live an active political life as a symbol of Japanese unity, rather than live in seclusion.

The new Japanese constitution was established on November 3rd, 1946. Blakemore’s contributions lay mostly in translating the criminal code to English, and abolishing certain parts of it, such as the “crime of being disrespectful” toward the emperor, and the “crime of adultery.” Blakemore also strengthened the independence of the nation, allowing the Japanese to rewrite the law as they saw fit. Blakemore was a staunch supporter of the democratization of Japan, but knew that the constitution imposed by Americans wouldn’t last after their military departed, and that they might revert back to an authoritarian dictatorship. It’s widely regarded that had Blakemore not been in Japan during that period, Japan might not have the freedoms they do today.

Fighting for a fair deal in Japan

Blakemore decided to leave the military and return to life as a civilian lawyer. He didn’t leave Japan, however. He had a belief that the country’s lack of knowledge of international trade would make it ripe for exploitation by foreign powers, so he tested and completed the Japanese bar exam in 1950, becoming the first westerner and American to be admitted to practice law in Japan with full courtroom status.

Blakemore founded the firm Blakemore & Mitsuki in Tokyo, and began negotiating for fair trade in Japan as American corporations like GE and Rockefeller began to enter post-war Japan for trading. Thanks to Blakemore’s legal backups, the Japanese industry steadily gained American technology to the point of surpassing America in some ways, such as in the automobile industry. Meanwhile, Blakemore & Mitsuki grew and gained a reputation as a prestigious international law firm. Blakemore continued to practice law there for 38 years. Blakemore and his wife moved back to the United States in 1988 and made their home in Seattle, where they founded the Blakemore Foundation. When Blakemore died in 1994, his obituary was printed in the New York Times.