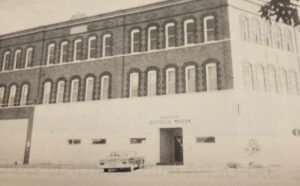

Rachel Whitney, Curator,

Sapulpa Historical Museum

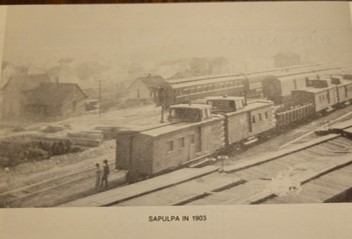

Locomotives. Engines. Rail transports.

In this area there are a few railway companies that stand out in Oklahoma history. The Missouri, Kansas, and Texas (MK&T) or better known as Katy. Atlantic and Pacific (A&P). St. Louis and San Francisco Railway (Frisco). Union Pacific/Missouri Pacific. Burlington Northern-Santa Fe (BNSF). Kansas City Southern. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe. Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific. Kansas City, Pittsburg, and Gulf.

“Kansas demanded an outlet to the Gulf of Mexico, and plans for a transcontinental railroad from St. Louis to the Pacific along the 35th Parallel were being made at the time. By 1870 already a total of 52,900 miles of railroad existed in the United States, with 1,350 miles in Missouri and 6060 in Kansas, but none lay within Oklahoma.”

Transportation in the Industrial Revolution boomed, connecting rural areas to towns to cities to states to coasts to borders and then to territories.

But, after the Civil War, the “railroad development lagged” in the Indian Territory. “The post-Civil War Reconstruction Treaties between the U.S. government and several Indigenous nations after 1866 stipulated that on north-south and one east-west railroad were allowed through the territories.” Congress authorized a land grant to aid in the construction of railroads through Indian Territory.

“Congress had stipulated that the first railroad to reach a certain point on the Kansas border, near Chetopah, was to have the right to cross through Oklahoma, and the MK&T won the competition with the Kansas and Neosho Valley company. The Katy line reached the River late in 187. Meanwhile, the Atlantic and Pacific had entered Indian Territory with a line from Pierce City, Missouri to Vinita.”

“By 1880s Indian Territory was seen more and more as a barrier to commerce and traffic between the neighboring states. Congress now took measures to allow further railroad construction through Oklahoma.” Tulsa, being on the river, got the Katy railroad to come through the city. Red Fork became an important cattle shipping point to the east.

There is a story that the railroad construction foreman discovered he was 15 miles short of track on his contract. With this possible mishap, the tracks lead to Sapulpa. Since cattle and timber at the time was not enough business to warrant a railroad in these parts, the Atlantic and Pacific went into receivership. Oklahoma City citizens offered bonuses to get the line extended to Oklahoma City and as a result in November 1885 the St. Louis and Oklahoma City railroad was formed. And completed to Oklahoma City in 1898. This outlet into Oklahoma Territory helped Sapulpa business expand.

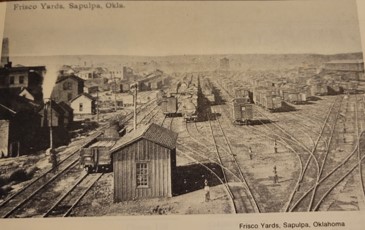

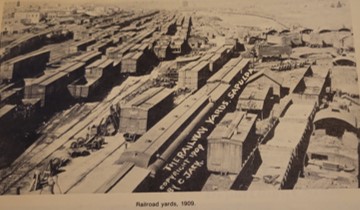

In December that year, the St. Louis and San Francisco bought the property of A&P and a line from Sapulpa to Dennison, Texas, called the Red River Division, which was completed in 1901. In 1898, when Frisco took over, the Frisco had a yard force of one man; in 1905, it had 200 men; in 1906, it had about 400 men who had their quarters in Sapulpa.

With the great workforce in Sapulpa, more and more trains entered the Sapulpa station.

But an accident was waiting to happen.

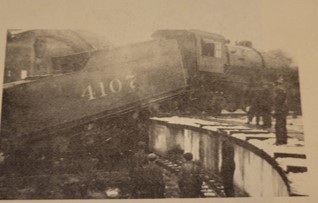

This week in Sapulpa history, “a steel demon” ran wild.

“A thunderous free lance, a mad, unguided locomotive, tore out from the local roundhouse and backing up on his hind legs, took a rear-end dash for Tulsa. Immediately, a reign of terror began among the local officials and the wires were kept hot.” It was thought that someone took the engine out of the yards and ran it up the tracks for about a mile.

Then turned it loose.

This was on the main line heading for Tulsa. Incredibly, there was no traffic on the tracks. It had a clear track all the way through Taneha, Red Fork, and West Tulsa. The tracks had just been cleared to allow a passenger train from Oklahoma City to pass through the area.

“The departure of the unguided iron monster from the yards at Sapulpa was discovered a few minutes after it had leaped away. Through Tanaha, it raced at unrestrained speed, vibrating with joy of being uncontrolled, the escaping steam resounding like the sibilant utterances of a conquering demon.

“Red Fork was passed through. The engine had raced over eleven miles of empty track at that time without the firebox being replenished, and the labor began to tell in the speed, which was yet sufficiently fast to restrain any thought of boarding gate orgy-bent despot.

“Throbbing through Red Fork hills and sweeping around many curves at this point in the track, perceptibly tired the runaway. From the terrific speed at which it went through Taneha it was proposed to try stopping the engine at the AVW junction at West Tulsa.”

Heroically, two men working for the station broke the lock on the switch box. M.L. Hawley, an engine man, and Officer John McLaughlin, “started out to put a stop to its wild career.”

The pair took a chance to stop the runaway train engine. “Taking their stand on either side of the track they daringly leaped upon the engine as it started past.” The engine began to slow, “according to the men, at a speed of from 12 to 15 miles an hour.”

Finally, the two men were able to stop the engine by pulling the lever before it crashed.

“Had the engine not been captured it would have crashed into six freight cars standing on the switch.”

Luckily, the only injury was a bruised leg from Officer McLaughlin.

(Oklahoma Historical Society; Sapulpa Light, December 3, 1909)