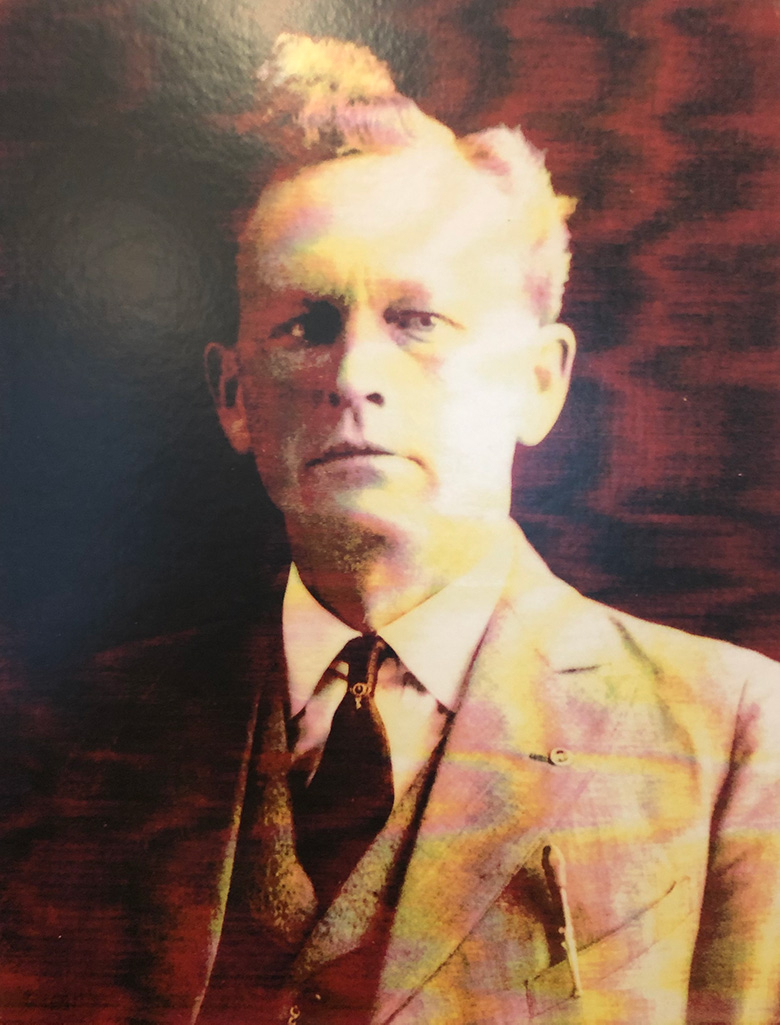

On the third floor of the Sapulpa Historical society hangs a faded reprint of a photograph of S. E. “Shep” Brumley, the Sapulpa policeman who was gunned down in an ambush on December 31, 1922.

Scarcely a year and a half earlier, Tulsa had been embroiled in what would go down as “one of the worst incidents of racial violence in the history of the United States.” The recently re-dubbed “Tulsa race massacre” that claimed the lives of 36 people and destroyed the wealthiest black community in the United States at the time, began with a highly-questionable assault of a 19-year-old black man on a 17-year-old white girl, was spurred on by now-disputed newspaper coverage from the Tulsa Tribune, and culminated into what was officially recognized 75 years later as the city conspiring with a white mob of citizens against black citizens. A blight on Tulsa’s history, the city has been trying to make amends ever since.

Eighteen months later and thirty miles away, Sapulpa was about to reach its own racial boiling point in an event that would lead to one of the town’s most notorious criminal fugitives, as well as claim the life of patrolman Shep Brumley.

The Ambush and The Response

It began when the police received a call about a fight at an undisclosed location. When they arrived, there was no fight and a Dr. James Rawls told the police the men they were looking for were in a café owned by Ed Glass. When the police opened the door, they were met with a barrage of bullets, killing Brumley and injuring officer R.D. Adams before the remaining officers managed to fight their way inside, only to have those responsible escape out the back door.

That same night, police rounded up a group of “colored thugs” that were posing as law officials and holding people at gunpoint while they were robbed in their own homes. They were quickly arrested and jailed, but evidently had nothing to do with the ambush that had happened earlier.

As a response to both incidents, Sapulpa law enforcement cordoned off the African-American community and asked that everyone—black or white—stay in their homes that evening. The town followed the instructions and there was no destruction caused.

Interestingly, it was The Tulsa Tribune that commended the town and it’s officials who “acted quickly and promptly to quell any problems.” The Tribune said the situation had resolved itself thanks to “aggressive vigilant leadership and sober citizenship”. The Tribune made no reference to their own handling of a decidedly less explosive situation in 1921.

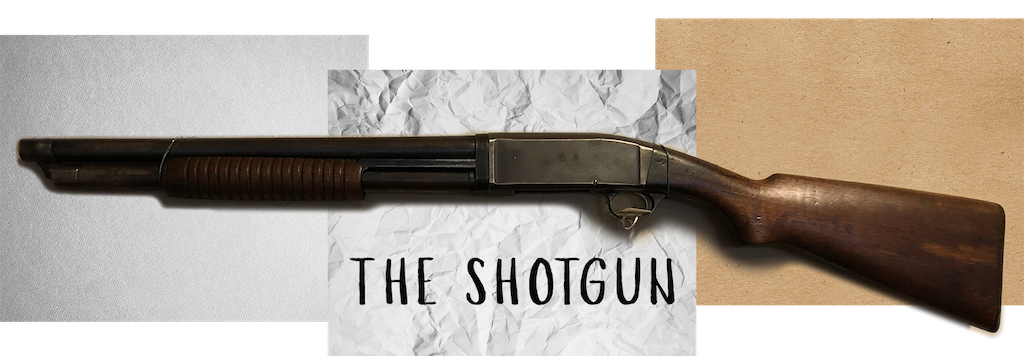

The next day, a letter of appreciation was sent to the Herald by “a group of colored citizens” thanking officials for their prompt handling of the thugs and pledged to do their part to keep mob violence down. A short while later, one of those who signed the letter also presented the Sapulpa Police Department with a shotgun that had an engraving that reads “Given by the colored citizens to the Commissioners of the City of Sapulpa, January 1923.”

Today, that shotgun hangs at the Sapulpa Historical Society near the photo of the slain officer Brumley. Together they present a somber reminder of what could have happened had “aggressive vigilant leadership and sober citizenship” not won the day.

But what of Ed Glass?

Glass in Mexico

Sapulpa Police began to pursue Ed Glass, the owner of the café in which the ambush happened, and one of those believed to have been involved. Ed’s wife Henryetta was arrested twice and questioned, but she steadfastly refused any knowledge of the shooting or her husband’s whereabouts.

By May of 1923 Glass was believed to have fled to Mexico. Sapulpa police sent John Imber, a close friend of Officer Shep Brumley—as well as a former deputy of the Mexican government—to retrieve Glass.

The story goes that Imbler found Glass and was making an attempt to smuggle him across the border, as the Mexican government had not yet been recognized by the United States. Imbler later expressed concern to Sheriff Abner Bruce that Mexican officers might be waiting to rescue Glass. When Glass began a desperate attempt to escape, Imbler shot him through the heart and left him in the desert. It’s been speculated that Imbler killed Glass merely to escape the difficulty he might’ve had bringing Glass over the border.

In any case, we’ll never know, because the man that Imbler killed in Mexico turned out to not be Ed Glass, after all.

Will the real Ed Glass please stand up?

Four years later, In September of 1927, Glass was found and arrested in Oakland, California, where he was running a small lunch stand. Glass freely admitted to shooting Officer Brumley but stated that it was in self-defense. According to Glass, the officers were not wearing uniforms and Glass thought he was being robbed; he only shot when they shot first.

Despite the protest of over 1,000 African-Americans in Oakland and San Francisco, the Governor of California signed extradition papers that would require Glass to return to Oklahoma to face trial for his charges. Glass tried to appeal his extradition to Federal courts, but by June of 1928, Glass had exhausted his legal options and was forced to return to Oklahoma for the trial. He began telling police how he had ended up in California after spending a few years in Chicago but had never been to Mexico. He stated he had never had any contact with anyone in Sapulpa during the time he was gone.

The Trial

The trial of Ed Glass finally began in February of 1929. During jury selection, potential jurors were asked about whether they believed in the death penalty, whether they were currently or had previously been members of the Ku Klux Klan and whether they believed they could “give a Negro a fair trial.” The defense submitted that being a member of the KKK should get them removed as a juror. Judge Harris disagreed and overruled the contention.

The trial lasted several days, with the defense arguing that Glass thought he was being robbed and when reaching for a gun, knocked over a bucket of bolts, which started the police shooting. Glass was eventually convicted and sentenced to 99 years in jail. Glass himself said that he’d never expected the case to be handled so fairly and he was grateful to get life in prison instead of the death penalty.

The Escape

A year later, Ed Glass had built up a trusting relationship with the Warden of the state penitentiary in McAlester and was eventually cooking for him in his home. Seizing an opportunity one day, Glass escaped.

In December of 1931, a man resembling Glass was arrested in South Carolina, but a fingerprinting determined that he was not Glass. Police were astonished, as the man resembled Glass in every way, down to the scars he had.

By November of 1932, the real Ed Glass was captured in Monroe, Louisiana. En route back to Oklahoma, he jumped out a bus window and escaped again. This time, he was never found.

This story draws heavily from the book “Sapulpa, OK! The Greatest City in the Known World” by Pete Egan, and on reporting from the Sapulpa Herald during the 1920s and 1930s. Egan’s book can be purchased at The Sapulpa Historical Society & Museum, 100 E. Lee Ave. The Sapulpa Historical Society celebrated its 50th anniversary in August of 2018.