Editor’s note: this is the first of a two-part series exploring the history of Sapulpa’s railroad industry.

By Cecil Cloud

Fred Harvey never set foot in Sapulpa, but the eating house which bore his name served the city for forty years.

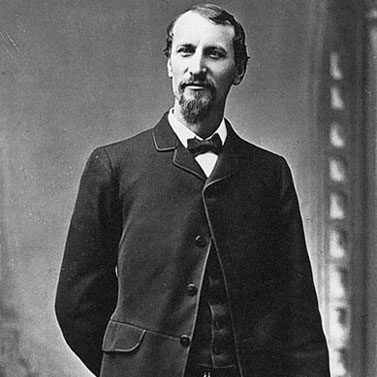

Born in Great Britain in 1835, Harvey came to America in 1853 and learned the restaurant business from the bottom up, starting as a busboy and pot scrubber in New York City. He worked his way up and out, and ventured beyond the limits of Manhattan.

After stints in New Orleans and St. Louis, Harvey went to work as a general agent for the Hannibal and St. Joseph railroad after his business partner in a restaurant skipped town. The Hannibal and St. Jo was the first railroad built west of the Mississippi and was always an industry leader. Fred’s logistical experience with the St. Jo would be of use, soon. Another partnership, in two eating houses on the Kansas and Pacific Railroad, also failed. In 1876, Harvey entered into a handshake deal to operate eating houses on the fledgling Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. This time the venture flourished.

Railroad eating houses in the 1870s had an evil reputation. With only 20 minutes to feed the passengers, many missed their meals—or missed their trains when they lingered over a ham sandwich and bad coffee. Dishonesty and violence was also a feature of frontier dining. A racial incident in New Mexico led Harvey to turn east to hire young women of good character to work as waitresses in his restaurants. They became known as “Harvey Girls”. His sites always featured three urns full of good coffee, and good food served quickly, thanks to a system of orders placed in advance by telegraph.

Here’s an aside: 1876 was only ten years after the passage of the Pacific Railroad Act and less than seven years after the completion of the first transcontinental railroad—but by 1876 the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas had built from Kansas across Indian Territory to Texas, using many of the same Irish laborers who had built the Union Pacific. The end of the war had cleared the way for a frenzy of railroad building. Both the Kansas Pacific and the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe were products of the transcontinental craze which would last into the Twentieth Century.

Fred Harvey was an innovator. He created the first national restaurant chain, and one of the earliest nationally recognized brands. “Your host is Fred Harvey” ran the motto, and Fred Harvey’s signature would remain the company logo until the end.

The Atlantic and Pacific railroad arrived in Sapulpa in 1886 and promptly stopped. It built a “wye” (pronounced “why”) for turning trains with the south end lying along what would become the route of Water Street. The history of the American West is written in the tales of wild, transient end-of-track towns. Sapulpa stayed an end-of-track town longer than any other. A series of downturns and panics and reorganizations kept the rails from advancing until the late 1890s. By the end of that time, The Atlantic and Pacific was no more and its successor, The Frisco had come to be 100% controlled by The Santa Fe.

With Santa Fe ownership came the Fred Harvey deal. In the 1890s, the Harvey Company was looking for wider markets. Fred was in declining health, and he and his “Tenth Legion” executives worked to ensure a smooth transition of power in the event of his death. The Harvey Company would continue under his name and signature when the next generation took over.. The new houses on the Frisco would be billed as “The Frisco Eating House—Fred Harvey, Manager.”

In 1896 a Fred Harvey Newsstand was operating at the old Sapulpa Station, which was located just east of Main on the south side of the tracks. Stephan Freid, writing in Appetite for America, says the Harvey House was built in 1896. Local sources say the two-story frame Harvey House was built just east of the station between 1898 and 1901. The Santa Fe had lost its controlling interest in The Frisco by 1899. Fred died in Leavenworth, Kansas in February 1901—but his son, the men of the “Tenth Legion”, and the Harvey Girls carried on.

The railroad starting building again. The St. Louis and Oklahoma City—later the Sooner Division of the Frisco—built west from Sapulpa in 1898. The arrival of this line spurred growth in the City of Oklahoma, which began life as an old boxcar set out as a station beside the Santa Fe line in 1887.

Frisco’s Red River Division was built south in 1899. The two lines met at the current wye near Hobson Street. Sapulpa became a division headquarters on the Frisco in 1901. Frisco launched a new train called “The Meteor” in 1902. Tulsa made its first bid for the shops and yards in 1902 but was turned down due to the poor quality of Tulsa water. This was the start of a twenty-five-year struggle between the railroad and the two towns. Sapulpa’s leaders, confident in the strength of their city, foresaw a need for a new station that could handle up to five lines, and plans were made for a large brick station at the new wye. One early plat showed the projected station lying along the Sooner Division track, but the station as built lay along the Red River Division.

The railroad built a three-story brick YMCA at North Elm and the tracks—just north of the France Hotel—in 1905. This building, the only one of its kind in the Twin Territories, featured a gym in the basement, a reading room and lecture hall on the first floor, and sleeping rooms for trainmen on the top floor. Like other railroad facilities, it did not survive the shift to Tulsa, and was closed and torn down in 1929.

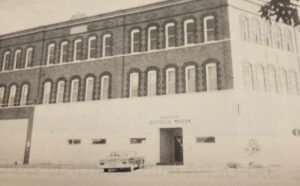

The new station opened on June 8, 1907, six months before statehood. It stood at milepost 437.2 on the Frisco Mainline from Saint Louis. The telegraph call sign was “SQ”. It was big—with space for a 40 room Harvey Hotel, newsstand, lunch counter, and dining room. It included an Edison electrical plant and Edison lights. A note handwritten on an old postcard states that the screens for the building were “worth $700”. The roof was red barrel tile. Frisco Stations and Harvey Houses of the day included the latest in cooling—electric fans. High ceilings also helped keep the public areas cool. The Harvey Brand included consistent décor. Lunchrooms on the Frisco featured grey tile floors with white accents, dark woodwork, and high ceilings with dark beams. The centerpiece of the lunch counter was three silver urns of coffee.

Crisp white napkins waited on the counter beside serviceable china. Your host, Fred Harvey, provided fine food fast, through a system of planning and standardization, the first such system in America. Meal orders, taken in advance, were telegraphed ahead from an earlier stop. When those orders arrived, the kitchen crew and Harvey Girls sprang into action. The Harvey system used a “cup code” to indicate to servers what to pour. Passengers could be served almost as soon as they were seated. The Harvey Dress Code required gentlemen to wear jackets in the dining room—and each House kept a few “loaners” on hand for those gentlemen who were caught short. The Harvey headquarters in Kansas City bought in bulk, and in some cases, such as beef cattle, produced their own. Harvey ranches and their resident cowboys were legendary in western Kansas. Coffee was purchased in bulk from a Kansas City roaster. Harvey kitchens included huge walk-in iceboxes.

The ground floor featured the hotel office on the south, the kitchen toward the center with the restaurant to the north, and waiting rooms and toilets north of that. The newsstand was in the north end of the building, with the waiting rooms. The Harvey Hotel rooms were on the second floor. Harvey Girl living quarters were on the top floor of the transverse section. If you’ve seen old photos of the depot, the hip roof of that section projects on either side of the tower at the third-floor level. A similar arrangement housed the Harvey Girl quarters in the station at Guthrie. Fred Harvey company policy called for two entrances. One stairway went directly to the kitchen. The other passed in front of the Harvey Matron’s doorway. The Harvey Girls shared rooms, protected by the Matron and the kitchen staff. This system of chaperonage worked…mostly. It was said that Fred’s greatest contribution to America was providing the West with wives. Many girls left the Harvey service to marry ranchers and businessmen, and descendants of some of our Harvey Girls still live in Sapulpa.

“The Frisco Eating House” name was in use early. An old pass issued for meal discounts using that name is dated 1923. The subheading on the pass reads “Fred Harvey, General Manager”—the enduring Harvey Brand, twenty-two years after Fred’s death.

Old photos of our Harvey Girls show bits of the station grounds as background. The grounds included station gardens, storage buildings, a two-story yard office to the west, and a large brick express agency station to the south. Depending on the season, the Harvey Uniform varied: black dress in winter, white apron over white dress in summer. The Sapulpa Historical Society book, “Sapulpa, 74066”, published in 1980, includes many photos of the kitchen crews, the Harvey Girls, and the interior of the Harvey House.

In 1909, pursuant to the requirements of Oklahoma Senate Bill 1 of 1907—the State’s first Jim Crow law—an addition was built on the northwest side of the building to allow for “separate but equal” lunchroom service. That “equal accommodation” also doubled the size of the white lunchroom. A common kitchen near the center of the building served both facilities. Our Harvey House kitchen left a lasting legacy—we’ll return to that later.

The Sapulpa building had no rival in the area. The new Tulsa Frisco station, a fine brick structure put up in 1906 had a Harvey Newstand, but no meal service. It continued to serve Tulsa until the Tulsa Union Depot was completed in 1931. The neo-Federal Frisco station at Bristow dates from about 1920. The station at Okmulgee was built in 1911, remodeled and gained a Newsstand in 1922. At least one of the Red River Division trains made a meal stop at Ada, but the reinforced concrete, Louis Curtiss-designed station there offered no food service.

The Depot was a busy place in the ‘teens, serving 14 trains a day, both through trains and commuter service to the oilfields. Harvey news butchers worked the trains out of Sapulpa—those on the Red River division working the ‘Ada Turnaround’. In September of 1912, Teddy Roosevelt made a speech promoting the Progressive Party from the rear platform of a train at the depot. The crowd, estimated at about 4000, applauded when Roosevelt remarked that the turnout was “better than Tulsa’s.”

Things were looking great for Sapulpa’s train depot, but the tides were turning as Tulsa began to make progress on the thing that cost them the railroad in the first place: water. In the next edition, we’ll look at how Sapulpa was involved in what became the worst train wreck in the state of Oklahoma, and what happened to the Harvey House?