Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part series on the history of Sapulpa’s railroads. Read part one.

By Cecil Cloud

Issuing train orders was a primary function of local railroad stations. The station agent and second and third shift telegraph operators were responsible for receiving and decoding train orders and passing them on to train crews. Operators at Sapulpa were involved in two major train wrecks in the area.

On August 24, 1907 the dispatcher at Sapulpa, Indian Territory, issued a train order with an incorrect train number to engineer Chris Bentz on east-bound train 412 to meet west-bound 407 at Red Fork. Station Agent Brooks at Red Fork tried to stop 412 at Red Fork, but the train pressed on, colliding with train 407 about ½ mile east of Red Fork Station. 4 died, including the engineer and fireman of train 412. The New York Times scooped the local papers, running this article on August 25. The Red Fork Derrick and the Sapulpa Daily Democrat ran articles on August 25 and 26, with key facts differing. The Derrick said seven cars burned; the Daily Democrat said 5 cars burned. The New York Times said 30 were injured; the local papers said 40-50 were hurt. The Times got the train numbers wrong.

On September 23, 1917, the dispatcher at Sapulpa handed orders to engineer John Ruhl to meet a troop train running as an extra at the Kellyville Station. Ruhl arrived at Kellyville and found a train carrying the white flags of an extra in the siding. Due to a change in operating procedures, Ruhl did not realize that the troop train was running in two sections. He proceeded on, and crashed head-on into the second section of the troop train on the Polecat Creek bridge. Thirty people were killed and about one hundred were injured. Most of the fatalities were in the “Jim Crow” combine at the head of the train. Both engineers survived, but newspaper accounts of the accident say that the engineer of the troop train “went mad”. Later writers say that the engineer of the troop train left the railroad, but returned to enjoy a long career. This discrepancy might be explained by the fact that the troop train, running in two sections, would have had two locomotives and two engineers.

On December 10, 1917, the Frisco office building at the “wye” burned. This fire may have been the end of the original Sapulpa Harvey House, as old articles had announced it would be moved for this purpose. More research is needed on this point. Also in 1917, The Sapulpa-Tulsa-Frisco struggle over the shops and yards went to court fot the first time. Ten years would pass, and Tulsa would launch an epic water project, before the issue was settled.

Increased railroad traffic when the United States entered the World War led to a “nationalization” of the railroads under the United States Railway Administration. The USRA instituted safety and working hour reforms that changed the industry forever. Railroad accident rates peaked in 1917, then plummeted under the USRA and remained down after the return to private management in 1920.

The new safety standards left the Kellyville wreck as the worst train in Oklahoma history. Through it all, the Harvey Houses kept on operating.

The young men who worked as relief telegraph operators had to be quick and accurate. Many were “boomers”. Moving from station to station and line to line, they worked up the ladder or moved on to other endeavors. One young relief operator who work the Frisco mainline from Catoosa to Bristow in the 1920s was handy with a guitar. According to railroad legend, he was working in the Catoosa station when Will Rogers stepped off the train, heard his playing, and advised him to make a career of it. Gene Autry graduated from high school and went to work for the Frisco in 1925. By 1928 he was singing on KVOO radio—but when he was working the third shift at the Sapulpa Depot, Autry was a fixture at Lawrence’s Cigar Store and City Drug on Saturday nights.

Many of Frisco’s name trains ran here. Through trains included the flagship “Meteor” running from Saint Louis to Oklahoma City, and offering a two-day connection between NYC and OKC. The Meteor carried through Pullmans to and from New York City and Washington. The Kansas City to Oklahoma City “Firefly” ran through Sapulpa. The “Black Gold” ran on the Red River Division, south to Dallas and Fort Worth. The rise of dining car service following the war cut into the eating house revenues. In later years, the “Meteor” carried a dining car between Tulsa and Saint Louis. The Harvey Company operated dining cars on the Santa Fe, but not, apparently, on the Frisco.

Sapulpa, Tulsa, and the railroad kept playing a complicated game in the teens and twenties. Tulsa business bought the relocation of two lines—the Midland Valley and the Avard Line—from Sapulpa to Tulsa. Donations of land and cash secured these deals. These were two of the five lines projected for the 1907 Depot. The ongoing failure to appear of the proposed Santa Fe line from Drumright to Sapulpa cost another line. Tulsa kept trying to get the Frisco shops relocated to West Tulsa, but the plans kept falling through. In the case of the roundhouse and engine shops, the dealbreaker was the poor quality of Tulsa’s water supply.

Reliable water supplies were scarce in the Territory. We’ll not get into that here, but in short: Sapulpa had the better water, so Sapulpa got the yard and roundhouse and shops. With the postwar oil boom, Tulsa’s ambitious leaders developed a plan to bring water from Spavinaw Creek in Eastern Oklahoma to Tulsa. When it opened in 1921, the Spavinaw Project was hailed as “the Eighth Wonder of the World”–and the balance of power between the rival cities shifted.

On January 11, 1927, Judge Franklin E. Kennamer of the U.S. Court in Tulsa granted a temporary injunction blocking an effort to stop the removal of the shops and yard from Sapulpa to Tulsa. On January 19, 1927, Judges Franklin E. Kennamer, Albert L. Reeves and Arba L. Van Valkenburgh ruled in favor of the railroad’s argument that the Oklahoma Corporation Commission had no power over the railroad, it being involved in interstate commerce. Judge C.B. Ames and Attorney Blakemore, representing Sapulpa, immediately filed an appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States. The railroad posted bond pending a Supreme Court ruling.

On the night of February 9, 1927, the roundhouse crew relocated from Sapulpa to Tulsa. Railroad workers spiked a new crossover in place in front of the Red Fork Depot, and on the morning of February 10 the shops and yard operations moved to the West Tulsa yard. This represented a loss of hundreds of jobs for Sapulpa.

The world was changing. The oil boom shifted to fields south and west of Sapulpa. The Frisco YMCA closed in 1929. The Supreme Court issued a ruling in 1929 upholding the railroad’s side of the yard move. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 led the Santa Fe to sell off its minority interest in the Frisco in 1930, and the Harvey House in Sapulpa closed on August 14 of that year. The Frisco went into receivership in 1932 and remained in trusteeship until 1947. The Frisco YMCA was torn down in 1934.

The Harvey employees looked for other opportunities. Whitney Martin had learned to cook at the Frisco Eating House. He mastered the Harvey menu, and took his skill on to a new venture. In 1932 Martin and his wife bought a second-hand trolley car in Tulsa, set it up at 515 E. Dewey and opened Wimpy’s Diner. The place was named after Popeye’s hamburger-eating sidekick, J. Wellington Wimpy the Third.

Wimpy’s offered 24/7 service and a classic diner menu, with Fred Harvey touches. Down to the final day in 1972, Wimpy’s served amazingly thin, tasty pancakes. Years later, your author, who grew up with those pancakes, read Stephan Fried’s “Appetite for America…” which featured a number of Fred Harvey recipes, including the “Harvey Girl Little Flannel Cakes”–the pancake Wimpy’s was still serving in the 1970s.

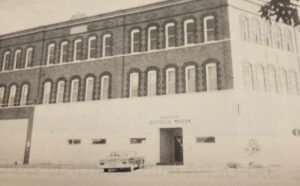

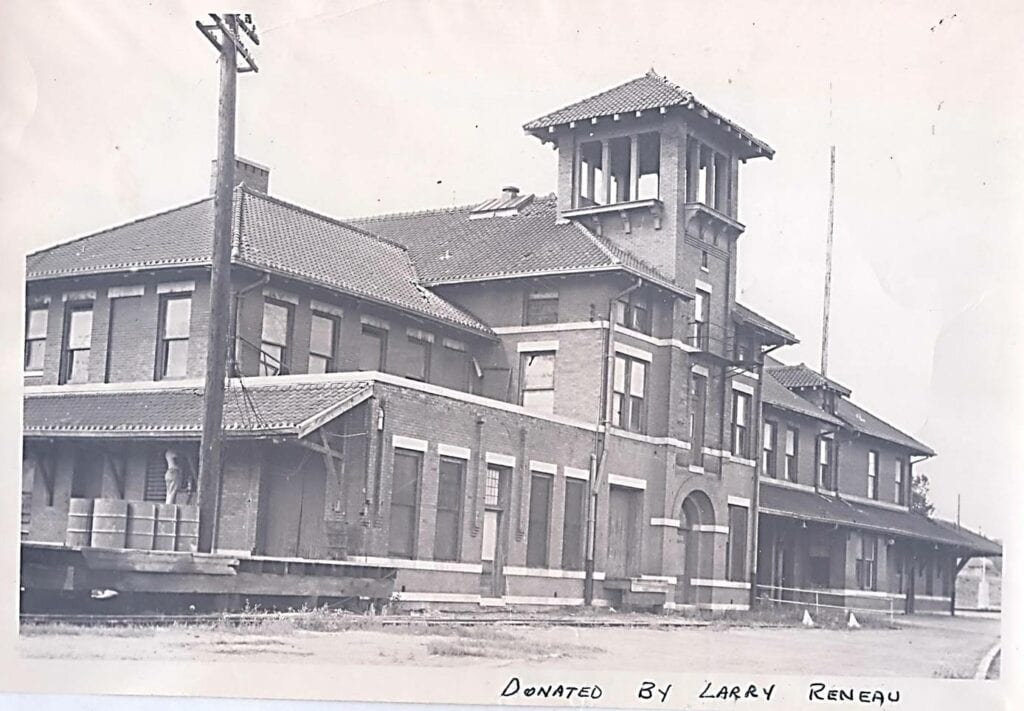

With the loss of the yards and the Harvey operations, and the decline in passenger service through the 1950s, the Sapulpa Depot became a white elephant. The massive building brought huge liabilities: taxes, insurance and maintenance. The railroad was only using a tiny part of that space as an agent’s office and waiting room. The railroad began cutting trains. Changes in Frisco’s management brought pressure to replace the large old stations with compact, modern ones. The Federal government announced the phaseout of the Railway Mail Service, and the profit went out of many trains. In May 1963, the Frisco moved two old passenger cars into the Sapulpa wye to serve as a temporary station.

On June 1st, 1963, the wrecking machines moved in, and the station and eating house which had served Sapulpa for 46 years was gone in three days.

The Sapulpa Harvey House closed long before World War Two, but the final generation of Harvey Girls served during World War Two. I spoke with two of them at the Frisco Depot Museum in Hugo in 2010. The Museum has a website and Facebook page. Three Fred Harvey Eating House locations survive in Oklahoma—at Hugo, on the Frisco; at Guthrie on the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe line through Old Oklahoma; and at Waynoka on the BNSF Transcon.

The Waynoka site houses a museum featuring Fred Harvey, Santa Fe Railroad, and Transcontinental Air Transport company history. The 1946 Judy Carland film “The Harvey Girls” gives a romanticized version of Harvey life The Johnny Mercer lyrics for the musical gave the world “On the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe” and “(Mr. Fred Said) The Train Must Be Fed”. This MGM Technicolor production includes Ray Bolger, Angela Landsbury, Chill Wills, and Cyd Charisse in her first speaking role. Byron Harvey, Jr.–Fred’s grandson—makes an uncredited appearance as a train conductor.