This story on “Dixieland Park” is compiled from a couple of different articles — one by the late James W. Hubbard for the Sapulpa Historical Society in a 1992 Sapulpa Herald story headlined: “Dixieland was a dream realized”; and the second by travel writer Jack D. Rittenhouse. We’re not sure in what publication that piece first appeared. It was given to me by Chief Eaton, current owner of the Dixieland complex.

This writer snatched the Hubbard story from the wall when doing the Sapulpa “Chief” Picker story a couple of weeks back.

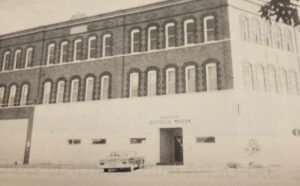

Dixieland Park along Sapulpa’s stretch of Route 66 opened in 1927. Traffic from the famous highway kept the park alive until 1951. The roller rink and subsequent nigh spot, longer. Eaton would later acquire the property and for years use it for his salvage and wrecker business. He still has a lot of old auto parts in the building, some vehicles behind the fences, and several of his classic and old race car restoration projects inside.

Hubbard, would be 91 on January 12 if he were living. He died 10 years ago on February 2.

Hubbard wrote that in the 1920s “realizing a great need for recreational facilities in the Sapulpa area, Clyde C. Hayes conceived the idea for Dixieland Amusement Park.”

At that time, according to Hubbard’s account, Hayes was the surviving partner in the Grooms and Hayes Grocery, located on Cleveland between Park and Water streets.

Hayes’ family, which included his wife Hazel, son Bob, daughter Edna May and mother in law May Grooms, lived at 602 S. Park.

“Hayes closed the grocery in August 1927 and entered into a partnership with his friend, Earl Townsend, to construct the park,” Hubbard writes.

“The partners bought 40 acres of land three miles west of Sapulpa on Route 66. A beautiful spring water creek ran through the property. At one time, a lake was created by damming up the creek and stocking it with fish. The dam later washed out and the lake was lost,” according to Hubbard’s article, however we have found several of these such lakes in the vicinity, evidently a practice at the time even for water supply.

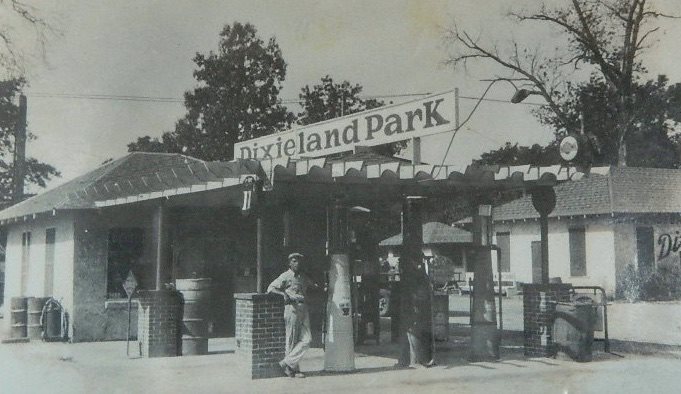

Dixieland opened in the spring of 1928, it boasted a large 100 by 150 foot swimming pool, a 50 by 80 foot bathhouse. Also featured were one room tourist cottages made of stucco, an auto garage and service station. There was a playground and special swimming pool for smaller children, plus a miniature golf course, barbecue pits and picnic tables and a cafe.

“The cafe specialized in hot barbecue, beer and pork sandwiches as well as the southwestern favorite, ribs,” Hubbard’s research revealed.

The swimming pool was filled with water pumped from 16-foot deep water wells. The water was very cold and had considerable mineral content. Reportedly,

Hubbard writes, “It was so pure, it was invariably graded as drinking water quality by state inspectors.”

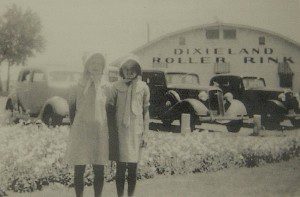

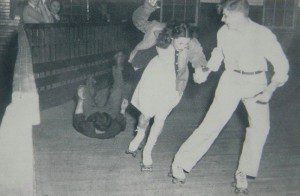

Later, Hayes’ brother, Harry, came from Bentonville, Ark. to build a large roller skating rink on the grounds and a home for his family just adjacent to it. He and his wife, Lorene, had a daughter, Jo Ann, who at the time of Hubbard’s story was identified as Mrs. Wayne Haag. She also is the source quoted in the Rittenhouse travel piece.

The park was popular in Sapulpa and its neighboring cities and soon became a popular gathering place for young and old alike, Hubbard recounts. There were swimming and skating parties, swimming lessons, club picnics and cookouts as well as “Miss Sapulpa” contests.

“Many came to spend the day and find relief from the heat on park benches that dotted the cool, shaded grounds,” said Hubbard. “People also came to admire the beautiful rose bushes grown by Hazel. Her flower gardens were designed to bloom continually during the summer months”

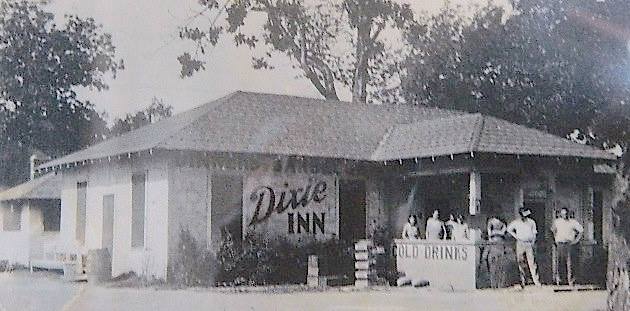

The cafe originally was leased to Red and Dona Wilson. In later years, Frank and Emma Buxton operated it. Small musical groups occasionally performed on the portico of the Dixie Inn, always drawing large crowds.

During the 1920s and the 1930s, adults could swim or roller skate for a dime. In the late 1930s, the fee increased to a quarter. The “kiddy pool” was always free.

The Dixie Inn Cafe featured barbecue sandwiches, beef or pork, for only 15 cents and was extremely popular. Many of Sapulpa’s leading citizens were regular customers.

During those early days, the service station sold gasoline at eight cents a gallon and oil at 15 cents a quart.

These were the Depression years and “hard times,” writes Hubbard the historian who also grew up during those days. “Many people lacked money and resorted to barter. It was not uncommon at all for Hayes to accept chickens and various produce instead of money in exchange for gasoline, oil or other park services.”

Many a traveler on old Route 66, “down on his luck” received a free handout at Dixieland. “No one was ever refused or turned away, if he needed help,” Hubbard said.

Dixieland Amusement Park managed to survive the 1930s dust bowl and Depression years as well as the World War II years in the 1940s, but finally had to close in 1951.

In later years, the skating rink became a honky-tonk and eventually was destroyed by fire, according to Hubbard’s article. The Dixie Inn Cafe was closed to the public and converted to a family dwelling. The bathhouse became a supper club operated by Buddy Stockton for a time. Eaton later acquired the whole complex where he would operate Turnpike Wrecker and his auto salvage operation until a few years ago. The defunct pool was filled with dirt from the new 66/33 highway build.

“The glory days of Dixieland Amusement Park are gone forever,” lamented Hubbard, but at the time of his researched piece. “many of the old-timers of this area remember when ‘Dixieland’ was the place to go.” Or borrowing from the words of the song of the south, “old times there are not forgotten.”

Rittenhouse plays on that “southern” theme in his travel piece.

“The rise of Dixieland Park began, appropriately, in the deeper South,” he pens. “Clyde Hayes and his brother, Harry, were simple country boys, farmer’s sons sweating in the fields of Bentonville, Arkansas.

“Love led Clyde to Oklahoma.” according to Rittenhouse. “In-laws lived in the oil rich town of Sapulpa. And after the courting was complete and wedding knots knit, Clyde found himself running a grocery alongside his father-in-law, Joseph Grooms.”

Grooms was a former railroad engineer who had “seen the country’s insides and kept his eyes peeled for money-making trends during trips down the tracks.” One day, he took his son-in-law aside and told him, “A man could find a fortune owning one of those new-fangled swimming pools.”

Hayes “marked the old man’s words.” In August of 1927, after Grooms had died, Hayes closed the grocery and formed a partnership with friend Earl Townsend. They bought 40 acres of property from Sapulpa businessman Max Meyer and “set out to hew a swimming hole into the side of Route 66.”

Meyer, who became even more famous in later years when his son Lewis wrote of him in “Preposterous Papa” had already explored some Route 66 highway trade.

Down toward Kellyville he maintained a string of tourist cabins. Regrettably, they too are gone. But back then Meyer and his layout inspired Hayes.

Dixieland’s marquee swimming pool was mammoth. Sixteen artesian wells kept it full of “shimmering blue.” The bath house was immense.

“The swimming pool had a high-diving board, and the water in that end of the pool was 18 feet deep,” Jo Ann Haag (Clyde’s niece) told the writer.

Belly-floppers shied away from the plank in the sky, but professional divers came to Dixieland specifically to try its springs. One was Johnny Weissmuller. The Olympic-swimming-hero-gone-Hollywood-Tarzan was well practiced in plunging from high places and delighted in taking Dixieland’s drop. “Clyde had got his land out there in Oklahoma and started with the pool,” Haag told Rittenhouse. “. . . he began talking to my dad about coming to Sapulpa and doing something. At the time, my dad was working for the Frisco Railroad. Like Clyde’s father-in-law, Joseph Grooms, he’d been all over the country. I believe it was in St. Louis that my dad had seen a roller rink.”

Harry Hayes and his wife Lorene moved to Sapulpa in 1928. The same year Jo Ann was born. They bought 10 acres of land adjoining Clyde’s property and squeezed into a Dixieland tourist cabin while Harry built a home — and the roller rink.

From its outside, Harry Hayes’ roller rink looked like an airplane hanger. Inside, fine-fitted maple made up its floor. Swimming at Clyde’s pool cost ten cents, so Harry also charged skaters one thin dime.

In the 1920s, roller rinks were a new thing. Many came to Dixieland simply to see what all the fuss was about. Meanwhile as roller skating became popular, so did Red and Donna Wilson.s cafe. Sandwiches and ribs were served up with Red’s Hot Sauce.

Buxton renamed the restaurant the Dixieland Club, and developed a more sophisticated menu featuring the likes of jumbo shrimp and fresh salmon. Such foods in these parts were not common. Buxton reportedly hired a private plane to fly the food in from the coast. People came from all over.

The glory days began to fade by the 1950s.

“Clyde couldn’t keep up with the filters that the state mandated for the pool,” Haag said of the glitch that dragged Dixieland down. “Around the same time, Mr. Buxton died of cancer. The Dixieland Club closed. My aunt and uncle made that building into a home. They lived there for quite awhile.”

Dixieland Park closed in 1951. For many years afterward, Harry Hayes’ determination saw the roller rink “roll on as a solo act.” Eventually, he leased and ultimately sold the rink to Buddy Stockton. Stockton turned the rink into a night club. Things became rather rowdy. Dixieland took on a new association. The building later burned. Dixieland’s old bathhouse remains the last of the park’s standing structures. Eaton leases out part of it.

—

This story was republished with permission from Sapulpa News and Views on Facebook