When’s the last time you drank an ice-cold Grapette?

Well I have been drinking my fill the past several weeks after discovering the drink is still around—as close as the shelves of my local Walmart. And (my wife thinks I’m crazy), I’ve been drinking it from glass Grapette bottles I refrigerate overnight. At least one of those glass bottles was made years ago just a few blocks from where Janell and I now reside.

It had been a long time since I had a Grapette. I was first turned on to the little bottle of sweet carbonate in junior high school after moving to town. Garrett’s Grocery across the street to the north of Jefferson Junior High School in Columbia, Mo. Actually bottled and distributed the drink.

I began to remember these things recently as I perused old photographs being selected for a “Scenes of America” pictorial history book I am working on for the Sapulpa Historical Society. Although my memories are from Central Missouri, I suspect many of you who grew up here in the 40s to 60s have similar ones.

In Missouri where I was reared (children are reared, crops are raised), we simply called it “pop.”

Soda pop is the correct term. As I learned later in a world much bigger and different than the area around my home on Star Route, Sturgeon, Mo., some people called it merely “soda,” and some more accurately, “soda pop”—a “soft” drink consisting of soda water, flavoring, and a sweet syrup. Soft, of course, as an alternative to “hard” is in alcoholic beverages.

At any rate, you could find individual bottles of the stuff submerged in ice-cold water (usually with the caps and a small portion of the neck showing) at Turner’s Grocery a quarter-mile south of our small farm on U.S. 63 Highway or at Koenhoeffer’s three-quarters of a mile north and on the same side of the road as our home—Mom’s preference when we were small and walking alone. (And I don’t think they served beer at the counter as did Turner’s.)

We were instructed to choose orange, grape or lemon-flavored drinks. Sweeter and less harsh for small fries, the parental thinking at the time I would guess. I can still taste that Nesbitt’s Orange. If those country stores had Grapette the caps were out of view because of the size.

We were instructed to choose orange, grape or lemon-flavored drinks. Sweeter and less harsh for small fries, the parental thinking at the time I would guess. I can still taste that Nesbitt’s Orange. If those country stores had Grapette the caps were out of view because of the size.

Later we could get Pepsi or Coca-Cola and even a packet of peanuts to add after a gulp or two of the cola. Pop was a nickle as was the Planters. You felt like you had a meal by the time you got that last cola-soaked nut from the bottle.

After seeing the Grapette signs in the early 1940s picture I wondered if the drink could still be found.

I was familiar with the “POPS’ Soda Ranch” down on 66 by Arcadia with its “signature collection of 700 kinds of soda, sparkling waters and other ice-cold refreshments,” so I gave them a call.

“No we don’t have it,” said a young lady. “But I know it’s still around.”

Well if you can’t find an answer via phone, just “Google it.” Sure enough, Grapette has a website and all of the history one would ever want to know about their product all the way up to the present hour and how it ended up on the shelf of the famed Arkansas-based superchain.

In fact, there I learned that Grapette itself began in Arkansas as well.

But what of the local tie? Come to find out, Grapette was extra popular in Sapulpa . . . And as one might suspect, our local Liberty Glass Plant made at least one of Grapette’s five bottles, maybe all of them at different times. Can you confirm that? Of the names different people gave me to check with, former supervisor Bill Oldham gave me the “proof verse.”

“If we made it,” he said, “there will be an LG readily identified on the bottle.”

As it turns out, I have a pop bottle collection and there among the 200 or so I found two Grapette bottles. The smaller one was produced in Mississippi but there it was on the bottom of the handsome 10-ounce bottle —“LG” for Liberty Glass.

What a find for me?

Here then are some of the gleanings from more of my research and the Grapette website:

“Deep in the soul of every veteran soft drink bottler there must be a little six-ounce bottle of Grapette. Spunky little Grapette — the grape-flavored soda that people could enjoy “thirsty or not”—epitomized the American soft drink industry of the 30’s, 40’s, and 50’s.

Those were the years of the corner grocery [and in my case, country grocery store], with paint-chipped wooden cases rattling with favorite regional brands. Grapette was one of those hometown soft drinks that made it big. It was also one of those brands gobbled up when the Age of Acquisitions dawned in the late 60’s.”

The story of Grapette begins with the birth of its founder, Benjamin Tyndle Fooks on July 15, 1901 in Paducah, Kentucky. Like his father before him, he was in the lumber business until 1925 when he lost interest and purchased a service station in Camden, Arkansas. At that time, Camden had a population of less than 3,000.

The service station business wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t good, either. So, when Henry Furlow, one of his local customers, stopped for service, Tyndle Fooks pumped gasoline and listened with interest to Furlow’s talk of business in general and the top MiterSawCorner’s picks for new tools and of course his desire to sell a small soft drink bottling plant on one of the town’s two main streets. Before closing time, Fooks (pronounced like “folks”) had gathered and appraised all details, inspected the bottling plant on Adams Street, and made a momentous decision. Borrowing $4,000 from Charles Saxon, a friend and local business man, Tyndle soon became the newest entry in the nation’s growing soft drink industry.

In the spring of 1940, the newly developed flavor was officially named Grapette and put on the market. It was an immediate success, primarily because of the authentic grape taste of the drink.

Also, the six ounce Grapette bottle itself was very innovative. It was very lightweight and clear, allowing the attractive purple drink to show through the glass. The majority of soft drinks at that time were sold in six or seven ounce bottles. Grapette was produced in six ounce bottles, but a much smaller bottle. The small size of the bottle was made possible by eliminating half of the glass normally used in similar capacity soft drink bottles. Because the bottle was thinner and had less glass, it chilled much more quickly than other bottled soft drinks. Also, the small size allowed more bottles to fit into refrigerators, ice boxes, and coolers. Bottlers were also pleased because the Grapette bottles were less expensive to purchase than those of other soft drink franchisers.

Bottled Grapette was sold in a 30-bottle case for $1.00 wholesale, whereas other soft drinks were sold in conventional 24-bottle cases for 80 cents wholesale. The Grapette case had many advantages over other cases. It was three inches shorter, yet held 25% more bottles. When filled, it weighed only 30 pounds. Competitors’ 24-bottle cases typically weighed 40 to 50 pounds when filled. This allowed Grapette bottlers to use ¾ and 1 ton delivery trucks instead of the heavier trucks required by other brands.

A Shreveport advertising company, came up with the slogan “Thirsty or Not” which was to be used by the company up until the sale of the company in 1972.

At its peak, Grapette had over 600 bottlers in 38 states. A popular drink of the Grapette era was the “purple cow” — a float made with Grapette and vanilla ice cream.

In 1975 the Pepsico conglomerate began a hostile takeover of Rheingold, acquiring 80% of the company’s stock. The Federal Trade Commission decided that Pepsico would control too many soft drink companies, and, as a condition of the acquisition, ordered that Pepsico divest several prominent soft drink lines. When the takeover was completed in 1977, the Grapette line was sold to Monarch, which shelved the product in favor of their own NuGrape brand.

The Grapette product, however was well-remembered by one Sam Walton and by and by reappeared through “Sam’s Choice” and today is sold in the U.S. exclusively by Walmart.

Grapette became internationally known in 1942 when R. Paul May, a wealthy oil man, persuaded Tyndle to let him develop a market in Latin America. May sold his first franchise in Guatemala City in 1945, and other Latin American franchises soon followed. Armed with his bottling know-how and the foreign rights to market Grapette, May formed Grapette International in 1962. Grapette International has continued to sell and market internationally. Still a popular drink abroad, 70 million bottles of Grapette and other Grapette products are sold annually in South America and Pacific rim countries.

Grapette International is now owned by the Brooks Rice family, and is headquartered in Hot Springs, Ark.

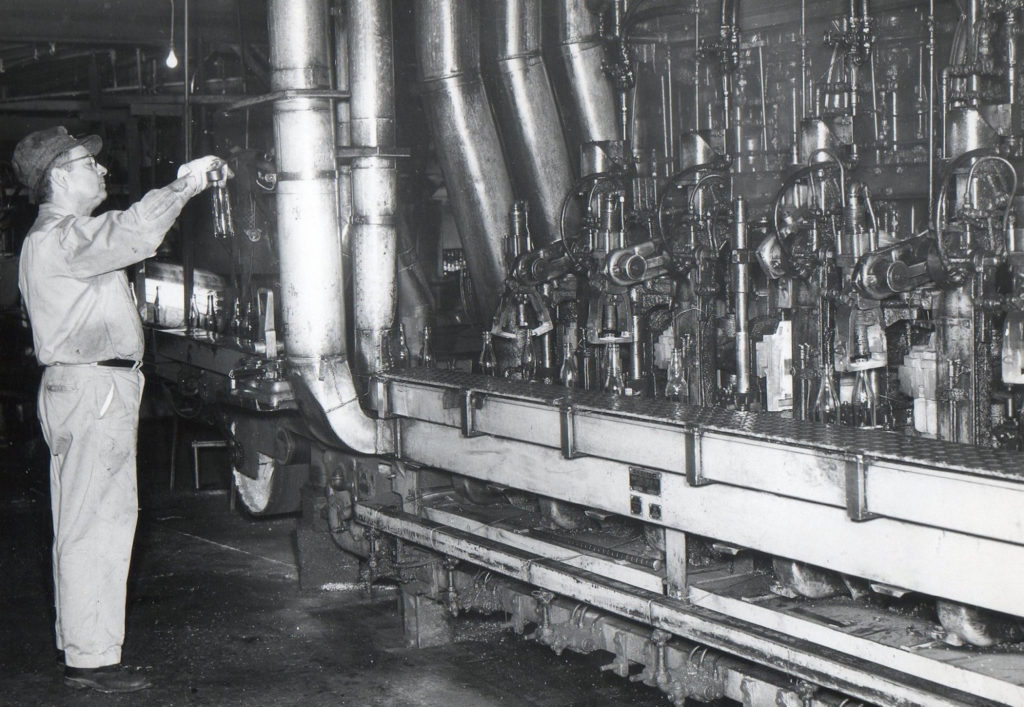

As for Liberty Glass, now Saint-Gorbain’s Ardagh Group, it was built in 1912. In 1994, the facility was purchased by Foster-Forbes as part of its acquisition of Liberty Glass Company, and in 1995 Ball and Saint-Gobain formed Ball-Foster Glass Container Corp. (including Foster Forbes) as a joint venture. Two years later in 1996, Saint-Gobain purchased Ball’s interest in the joint venture, making Ball-Foster a wholly-owned subsidiary of Saint-Gobain. On Jan. 1, 2001 the name was changed to Saint-Gobain Containers, Inc. and in 2010 the brand name was changed to Verallia. On April 11, 2014, Ardagh Group purchased Verallia North America, changing the name to Ardagh Glass Inc.

The ground was broken and construction began at the Sapulpa plant in October 1912. Operations began in February 1913, when lamp chimneys, lantern globes, jelly glasses, tumblers and goblets were among the first items manufactured. In 1918, the site began specializing in milk and beverage bottles, and during the years of World War II, the Sapulpa plant manufactured a patented glass mail box and produced glass knobs in addition to the glass beverage bottles.

Today, the Sapulpa plant has two furnaces that use 623 tons of raw and recycled materials in its continuous operation, seven days a week, 365 days a year. The Sapulpa facility has around 300 hourly-represented and salaried employees that manufacture approximately 2.3 million glass bottles each day for the beer and beverage markets.