Don Diehl

It was this time of the year in 1890 when Tommachichi (Tommy Jon Harjo) arrived at a terminus — not of his faith in God and man — but almost. He and the crew of photographers of which he had attached himself during a train ride from Kingfisher into northern Nebraska experienced something horrific — Following is an excerpt from the epilogue of the book: “INVASIONS: ‘Killing of the Indian.’”

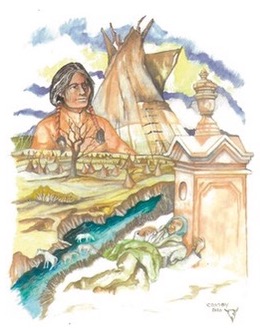

Beginning next week and to be offered throughout most of next year to area newspapers as a series is an abridged copy of the historic fiction novel by Sapulpa writer Don Diehl. The more complete work is self-published through Barnes and Noble.

The characters in the storyline are fictitious but the story itself, its setting, and time period are true to life. The book follows 15-year-old Muscogee Indian Tommy Jon Harjo from the Oktaha settlement in Oklahoma Indian Territory as he journeys across from the Creek Nation to Dakota Territory on an adventure prescribed by his grandfather as an alternative to formal schooling after the boy’s mission school at Eufaula was destroyed by fire.

Beginning at the back of the book then . . .

“The group from Wounded Knee Creek returned to the Stouffer ranch on January 1, 1891, after a blizzard-ridden two days of taking and making photographs, some of the most horrid in the early age of photography. Scenes of farm families on lawns, skilled Indians playing Stickball, shots of early towns and train depots, weddings, and school graduations would be much better fare than this kind of “hard news” photography.

It’s now January 3, 1891, across South Dakota. Graphic photos have been developed and printed, the horrendous stories have been filed and published. The whole world is waking up to what has taken place at “The Battle of Wounded Knee” — perhaps the last significant physical (very physical) and violent battle between the U.S. Government and its so-called Native population. Conclusion of the Indian wars; the ‘final solution’; the answer to “What to do about the American Indian;” indeed the final leg of the” invasion” of Native America. The Indians, as ordered have been repressed. But at what cost?

Many in the country, the whole world is aghast at what they have read and seen. Soon the words, “Battle of Wounded Knee” become “Massacre at Wounded Knee.”

Tommy writes in his journal, “The West has not been won, the West has been lost. There are no winners at Wounded Knee. All sides have lost. I feel lost . . . lost as I can be. There is no color anywhere I look, only grey, cold grey, is all I can see. I fear I might lose my faith. I am hurting, not because I’m an Indian, not because I am a descendant of first Americans, but because I am a human. I do not know what to do. I’ve tried to pray, but I can’t.”

Tommy has loaded Sagebrush on the stock car and leashed Bramble safely nearby. The chaps are across the saddle. The writers and photographers of whom Tommy had come to know on his journey were very somber now too. No more ”injun” taunts or the mocking of a young Indian’s belief system of a Creator God full of love, justice and hope. They filed their final stories for the day. The train is almost late waiting for them to finish telegraphing from the station to newspapers like Omaha’s The Daily Record, one of the midwest’s newest newspapers with a climbing circulation and Associated Press outlets and syndicates.

Tommy puts his journal away and begins to wipe at the forming tears again. He can’t help it.

James, and the man called “Big John” Ellis, often the source of his consternation — challenging his belief system, comes close. No sign of ridicule or taunt now.

“Are you alright Tommy?” Big John asked, placing his arm full around the young Creek’s shoulders. Tommy looks at the men, tries with all of his muster not to sob, then completely loses it. The tears flood his cheeks and fall on the chest of the hardened journalist. The man who had been his antagonist is now trying to comfort him. The sobs are growing more audible.

“If only Aunt Rose was here,” he thought to himself. “But I wouldn’t have wanted her to see any of this. Those little boys and girls . . . it would have killed her!” He choked back his tears. His heart kept on breaking. What of Uncle Jon, such open show of emotion seems a betrayal to the elder’s admonition to always “be courageous in the face of adversity.”

“Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged, for the Lord your God will be with you wherever you go.” — Joshua 1:9

“Massacre,” had become a much harsher word than “adversity.” It was a word too often used across the Old West and the whole of America as the storms of human embattlement on the frontier ripped the high sounding idea of a “Manifold Destiny’’to shreds. Still there has to be that goal of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” for the good of all living in a country only a few years after its 100th birthday.

“I feel my faith . . .” Tommy looked up. “I’m thinking you were right Mister John to question how a loving and just God could allow this kind of horror . . . this kind of evil.”

“Whoa! Don’t even go there, young man. You need to know something. It is because of your faithful testimony and confidence in your God that I — and I believe a couple of others ‘round here — agnostics at best, really — who have come around to your way of thinking. There has to be a God of justice that knows all and knows what to do about it. Who are we but pipsqueaks to question the Creator of the Universe?

“No, you are right Tommy, don’t be discouraged. I believe in your Christ. How can I, we, do anything but? All of this has not proven me right, Tommy. It has proven that you . . . you and your faith, have to be right. If not, what of this crazy world?

Now, it is a new year — 1891 has rolled into the final decade of the 19th century.

Lessons? One wonders, especially a young Creek Indian from the Muscogee Nation in Indian Territory/Oklahoma, who along with the host of newspaper reporters, writers and photographers were eye witnesses to a government solution to an “Indian problem.”

Very soon, Tommy’s Nation too — with treaties broken or suspended, promises upended — will be enveloped in the founding of a new state. That state’s name, like its territory, is derived from the Choctaw words okla and humma, meaning “red people” (commonly called the home of the red people). It also would become known informally by its nickname, “The Sooner State”, a reference to the non-Native settlers who staked their claims on land before the official opening date of lands in the western Oklahoma Territory — and the Boomers who wanted more land.

The Indian Appropriations Act just last year (1889) increased European-American settlement in eastern Indian Territory including Tomachichi Jon Harjo’s beloved Muscogee Creek nation. Thus Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory would be merged into the State of Oklahoma the 46th state to enter the union. Those wheels, as sure as these on Tommy’s train home, were rolling towards that terminal. (Oklahoma became a state on November 16, 1907. Tommy, now known as Thom J. Harjo is 22. And yes. you guessed it — finishing up degree work in journalism and photography at the University of Nebraska where both he and the Stouffer twins are students.

He and Becky Anne? Dating and making plans — well let’s just leave it at “plans.” You probably guessed that right too. Harjo learned how to operate a linotype machine earning college money. He may stay with that after college. Little Rosie now goes by Rose. She is attending Bacone University and plans to be an educator. She has been offered a position at Eufaula Boarding School as a seamstress. Grandparents, Uncle Jon and Aunt Rose McSchmidt are still healthy and even wiser (if that could be).

There was a letter-opening party in which the Harjo children were given the trove of love letters exchanged by their parents right up to the time of the river drowning. Thom thinks Rose’s idea of a “romance novel” is a good one.

That family photograph of Sam and Sehoy Harjo and their two small children, Tommy and Little Rosie, is still so very precious — as are the memories on the McSchmidt farm in Indian Territory. The two siblings often visit their parents’ grave in a family plot at a cemetery near Oktaha.

—

Next week: “A Journey Planned Around Kitchen Table After School Burns.” Diehl’s original book can be ordered by title or author’s name. Available through Barnes and Noble and Amazon (paperback or digital) it is 400 pages and features color art illustrations by Sapulpa artist Russell Crosby. At $19.95 on B&N and $25.42 on Amazon. Following initial feedback, future plans call for publishing the abridged edition sometime this next year and will carry only the adventure story and less bibliography. That basically is what is being offered readers of the newspaper series. Sapulpa Main Street director Cindy Lawrence McDonald has several copies of the book for sale at her office in historic downtown Sapulpa. Of course, again, it is available from Barnes and Noble, Amazon (both print and e-book) or from nearly any bookseller. (Google it by title or author name). The coming abridged copy made possible in part by patron Howard “Hoppy’’ Hopwood (an OKC area tribal leader and historian) will be titled “Tommy Hawk!”