Bill Mauch was formally inducted into the Centenarians of Oklahoma Hall of Fame as their 3,098th member at a party celebrating his 100th birthday on April 19th, 2025.

The Sapulpa Times met Bill at his house a few days before that golden celebration to talk about his childhood and what it was like growing up in a town starkly different from today’s Sapulpa.

“I remember the streets weren’t paved, no blacktop or anything. They were dirt and rocks and primarily sand streets,” he said. “When we bathed, we heated water on the stove in the kitchen, in big galvanized tubs.”

His father, Charlie Mauch, had come to Sapulpa from Chandler in 1919 looking for work, and after a job working at a refinery, he bought a half-interest in a grocery store called Southern Heights Cash Grocery. Charlie would load up his half-ton pickup with produce and peddle it in nearby towns like Kiefer, Kellyville, and Slick.

In 1924, Charlie and his business partner decided to take on a wet wash business. There was some tough competition from the two other steam laundries in town, but the men persevered, going door-to-door to obtain customers. In 1928, Charlie bought out his partner and installed dry cleaning, changing the name to Sunshine Laundry and Dry Cleaning. It was located in a small brick building that still exists today at 1101 S. Main Street.

Until the early 1930s, the Mauch family continued to heat their water using a wood stove in their 3-room house at the corner of Water Street and East Jackson Avenue in the South Heights neighborhood. Finally, Bill said they decided to bring in gas heating to the house by tapping into the gas line at Sunshine Laundry.

“We lived a block or so diagonal from the laundry, so we dug a ditch from our house to the laundry. Just went down the fence line in the middle of the block and then a short distance north and tied into the gas line. Didn’t have any permits or anything, I’m sure,” he said, chuckling.

Bill was the second-to-youngest of the four boys, but had a total of 9 siblings, including two sets of twins. He recalled the time in 1933, when his dad decided to add some square footage to the house to accommodate the growing family. However, instead of adding a bedroom or expanding a living area, Charlie Mauch bought a whole second house.

“My dad had bought a house a block and a half away,” Bill said. “They jacked up the house and ran skids underneath it, with wheels. And they pulled it by a team of horses to our house.”

Incredibly, the house was a perfect match to the one they were currently living in and they were able to join them together to form a larger home with almost no adjustment. “The width was right, and the roof was pretty well about like it should be,” Bill said.

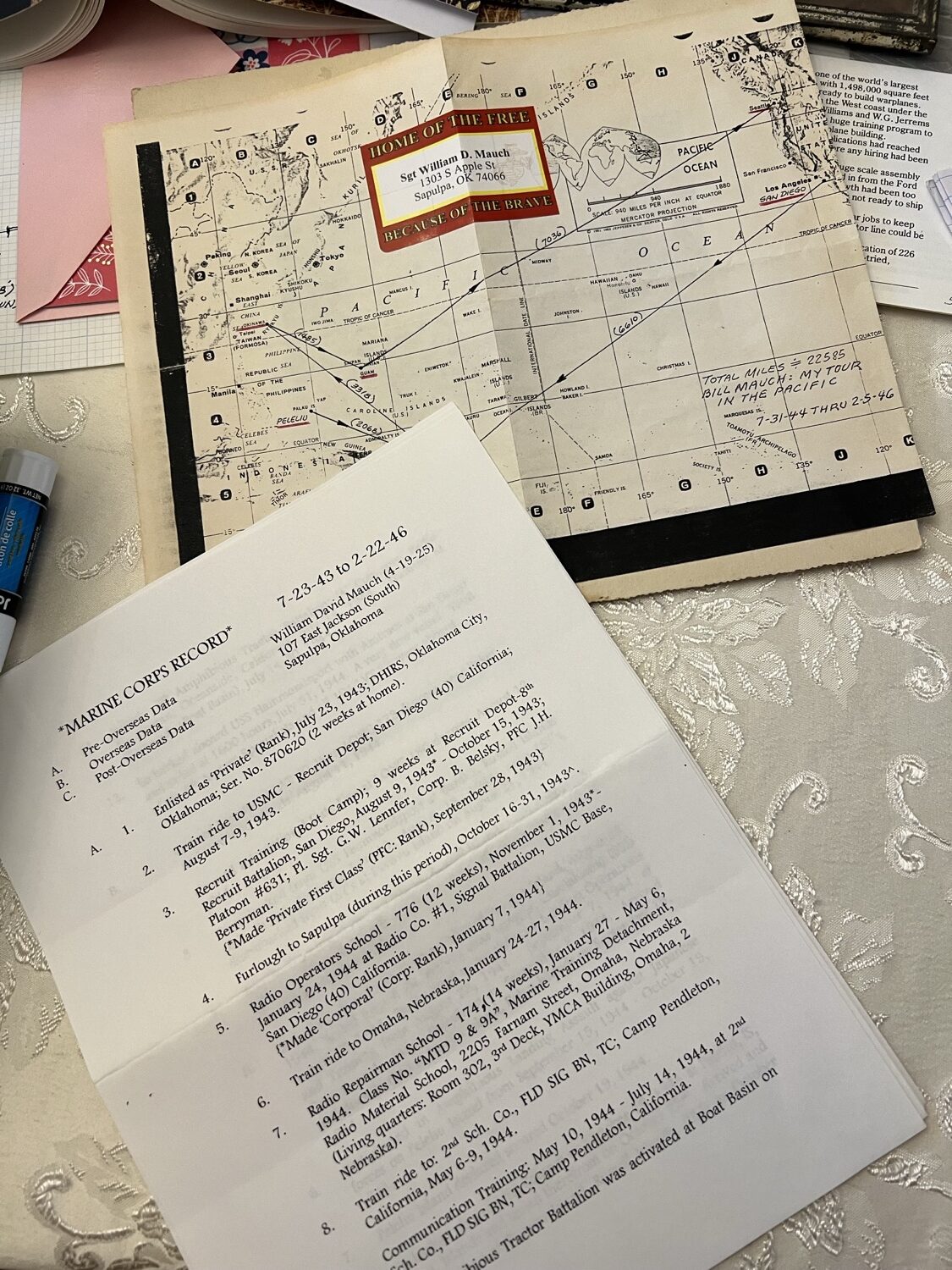

After graduating from high school in 1942, Bill wanted to do what most men did and enlist to fight in World War 2. Bill had skipped a grade or two and graduated at 17, making him ineligible to enlist until a year later. His first choice was to join the Air Force, but by the time he was drafted in 1943, the Air Force was at full capacity. He chose instead to volunteer for the Marines and was shipped out to fight in the Pacific.

Fighting in the Pacific during WWII.

Bill Mauch appeared on The Warrior Next Door podcast in February of 2025. In that episode, he discussed the train ride to San Diego before being deployed overseas.

“The train was just full of mothers and children, so it was hard to even get a seat. And every window was wide open, trying to catch a breeze,” he said. Seating was so scarce on the train that he said he spent one night sleeping on the 4-feet-by-4-feet trash receptacle outside the car.

The train ride took three days, and he still had to travel by bus to the Marine base. Later, he was shipped to Omaha, Nebraska, where he received additional training on radio operations and repair. He was assigned to work the radios on the Amphibious Tractors.

Though the Amphibious Tractors—also called “AmTracs”—were a versatile machine and able to go on water and land, they weren’t exceptionally fast. “Top speed was about 23 miles an hour on land, and 7 or 8 miles an hour in the water.” Mauch was one of two repairmen in his company, and they were responsible for 12 boats.

In 1944, he was deployed to the Guadalcanal to the island of Peleliu, and arrived in the middle of a firefight. “They had bombed the island, it was full of craters,” he said. “I was huddled in my foxhole, as the land crabs made noise all around. Everything frightened you. You’re just totally frightened to near death.”

On April 1st of 1945, he landed in Okinawa, Japan, the United States’ “Pacific Island Hopping Campaign” was in full force. Okinawa was the final island to be invaded, thus making it the “Final battle of WWII.” The day was simultaneously Easter Sunday and April Fool’s Day.

Mauch said landing on the island didn’t see much opposition, and that the Japanese were fortified further inland, mostly in caves.

“After we’d been there two or three days, we got directed to pick up a load in our tractor down the shore.”

The “load” would turn out to be seven Marines in body bags. Mauch says it’s a sobering reality of the standard operating procedure of amphibious assault during the war.

“On that island, we were constantly under threat to our lives,” Mauch said. “You have rifle fire, you have mortars, you have big guns and bombers every night. You have anti-aircraft shells that burst and can land on your tent. There’s just all these ways you could get killed.”

So it comes as no surprise that, according to Mauch, “one of the first things they determined upon landing (on the island) is where the cemetery is going to be.”

On April 6th, they endured the world’s largest kamikaze attack, as hundreds of Japanese pilots flew their aircraft directly into U.S. ships, aiming to inflict maximum damage. The U.S. Navy faced significant challenges in defending against these attacks, as the sheer number of incoming planes overwhelmed their air defenses. Several navy ships were damaged or sunk, and an estimated 400 or more sailors were killed in what was called the “U.S. Navy’s worst 19 hours of World War 2.”

Mauch said his battalion didn’t have the means to shoot down the planes, and so all they could do was watch as the planes hit the ships. “We watched them shoot down some of the planes, but we also watched a lot of those ships get hit,” he said.

By this point, the Japanese Navy was a shell of its original self and on April 7th, they sent what would be in football terms a “hail mary”—a single battleship called the Yamato with a skeleton crew on a one-way trip to Okinawa with the singular mission of beaching itself and fighting until it was destroyed. It was sighted well before reaching its destination, giving the US ample opportunity to attack, which they did; 300 US aircraft brought their full weight against the large battleship, sinking it.

It took 82 days to secure that island. At the start of the invasion, the Japanese troops were 100,000 strong. There were 1,850 Japanese aircraft involved in that campaign, of which 1,050 were kamikaze.

At the end of the Battle of Okinawa, the 100,000 Japanese troops had turned into 100,000 Japanese casualties, along with 50,000 American casualties, and an estimated 150,000 Okinawan civilian casualties. The battle caused twice the number of American casualties as the Battle of Iwo Jima and the Battle of Guadalcanal combined.

Mauch was in Okinawa, waiting to go to Guam and eventually to Mainland Japan, when the United States Air Force dropped the 2 atomic bombs, effectively bringing an end to the war. He finally arrived back on US soil on February 5th, 1946. He said the homecoming for those fighting in the Pacific was much different from the confetti and parade welcoming that the European troops had. “I remember being served refreshments on the train ride home,” he said. “That was about it.”

Back to Civilian Life

Upon his return, Mauch gained a degree in architectural engineering from Oklahoma State University and, after working three years for OG&E, got a job as an aeronautical engineer at McDonnell Douglas, where he remained for the next 33 years. Much like his work made history during World War II, his work at Douglas McDonnell made history as well, becoming instrumental in events like the Cuban Missile Crisis, or in California as part of the Skylab space project.

He met his wife Helen at a carnival, and they were married on March 19th, 1954. They were married for 70 years until Helen’s passing in March of 2024. They raised four children together, and now have six grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

Today, Bill Mauch still enjoys things like fishing and yard work when he can do it. He loves to visit with people and will talk about his life’s experiences with great detail and clarity. The VA Center for Development and Civic Engagement (CDCE) also celebrated Mauch’s 100th birthday. In their commemoration, they summed up Bill’s story as “a life well-lived, marked by service, love, and an unyielding spirit. His journey from a small town in Oklahoma to the heights of aeronautical engineering, his enduring marriage to Helen, and his unwavering faith and family values paint a portrait of a man who truly did it.”