“The Hatfields and McCoys have been called by historians the two most famous families that the United States has ever produced.”

That’s how Billy Hatfield began his conversation into the history of the now-famous feud between the two families that occupied the mountains of Kentucky and West Virginia.

Billy Hatfield, formerly the pastor of Faith Baptist Church in Sapulpa, is the great-grandson of Devil Anse Hatfield, the leader of the Hatfield side of the feud. Since his father passed in 2012, he’s the closest living relative to the famous Hatfield.

After an award-winning pastoral ministry spanning more than 45 years, Billy Hatfield now uses his namesake to spread the gospel.

In a recent meeting with Sapulpa Herald, Hatfield told us the feud that became so famous that it spurred depictions, in film, television, even cartoons.

Before the Civil War, the two families were cut from similar cloth. “There was a lot of poverty in that area, and just as you see in cities today, a lot of times they turned to something that can make easy money,” Hatfield said.

For them, the answer was moonshine. Both families—as well as nearly everyone else in the area—made corn liquor to sell to anyone who wanted to buy it. And for the time, the families got along fine and more so.

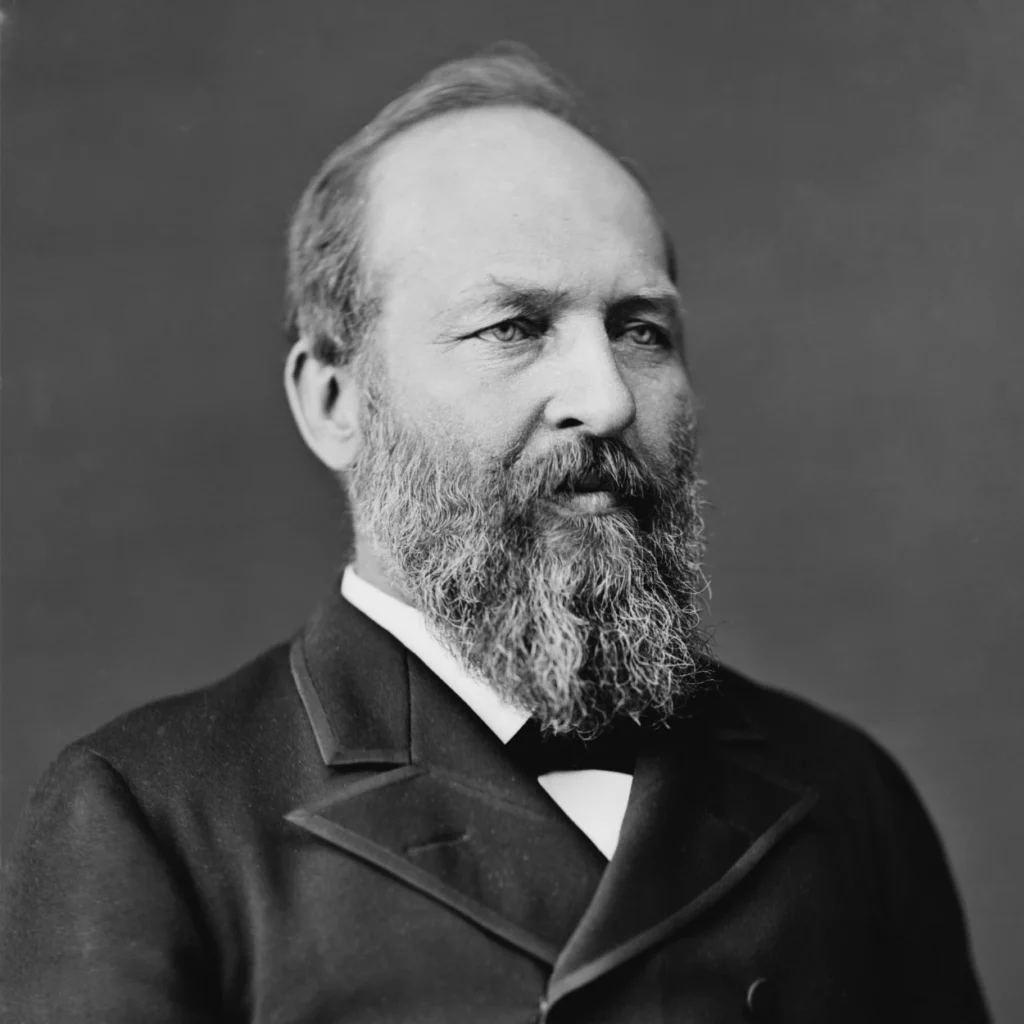

(Credit: West Virginia and Regional History Center, WVU Libraries)

“They intermarried; Hatfields married McCoys, McCoys, married Hatfields and they were getting along really fine until the Civil War came along,” Hatfield said.

There’s a rumor that the Hatfield-McCoy feud began because of a stolen hog. While a situation resembling that did occur, Billy Hatfield maintains that it was the Civil War that changed things—for everyone.

“Wars change everything, especially when you’re on the border of Kentucky and West Virginia,” he said. “Kentucky is a neutral state. They do not fight on either side. They did send 35,000 men to fight for the Union, but they also sent 15,000 men to fight for the Confederacy. They were also a slaveholding state.”

Virginia—and what would later become West Virginia—was also a slaveholding state, and it was home to a heap of trouble. “There were a lot of bad things going on,” Hatfield said. “They had formed a ‘Union Home Guard’ there and they were treating this war as an opportunity to become wealthy,” he said, detailing how this ragtag group of marauders from Kentucky would raid the towns in Virginia and steal the livestock and crops, burn barns and attack the homesteaders.

President Abraham Lincoln’s solution was to send in James Abraham Garfield—himself a future president—to clean house. He did so and became a war hero. But the future president’s insight into the situation would ring prophetic.

“He wrote in his journal, ‘the feudal flames will be yet unquenched,'” Hatfield said. “Every man just views his neighbor as someone he can profit from and steal from.”

Garfield’s Lieutenant had the same sentiment, according to Hatfield “He said long after we leave here and long after this war is over, what’s been going on here is going to have repercussions for years to come.”

They were both right, and the raiding and fighting got worse, but the feud didn’t officially start until they made the mistake of going after one of the best friends of Devil Anse Hatfield.

“My grandmother lived until 1990, telling us all the tales about the feud,” Hatfield said. “But what happened is they raided a guy named Moses Christian’s farm and did very bad things.”

At the time, Devil Anse Hatfield and the others were in the Confederate army.

When they got word of Christian’s farm, a lot of them deserted the army and came home and fought as their own home guard.

“Kentucky wasn’t in the war,” Hatfield said. “In Virginia, every able-bodied man had gone off the fight. So these farms were helpless women and children and old people. And so the marauders coming out of Kentucky just had it made they can go in there with no resistance.”

Devil Anse and his Confederate brethren brought the resistance home. “They began to fight back,” he said.

At the time, most of the men from both families had fought for the Confederacy. Asa Harmon McCoy, who fought for the Union, was hiding in a cave because he heard that Hatfields were “gonna get him,” as Billy Hatfield put it. He was found murdered, and his death was attributed to the Hatfields. “So that started some bad blood,” Hatfield said.

Accusations piled up, and not always in the mountains, but even in the courtroom. “They were very litigious,” Hatfield said. “They were always suing each other over stuff all the time.”

There were other, smaller incidents (including the hog story), that happened, but Hatfield says things didn’t really get going until an election day party. “Election days are really big there,” Hatfield said. “Everybody comes together, they all have the vote, they have big parties, they pass the moonshine jugs, they trade guns, and they swap stories.

It was at one of these parties that Johnse Hatfield disappeared into the woods with Rosanna McCoy. Like an Appalachian version of Romeo and Juliet, the couple returned after everyone else had left the party, but couldn’t go home because of who they’d been with. Rosanna turned up pregnant, Devil Anse refused to let his son marry her, and she eventually went to live with an aunt, where she had the baby, which died a few months later.

Finally, the tensions boiled over at another election party sometime later. Four McCoy boys jumped Devil Anse’s brother Ellison Hatfield, and though Ellison held his own for a while, one of the McCoys pulled a knife and stabbed him 26 times, and then shot him.

While Ellison was still alive, Devil Anse Hatfield gathered a small army and met the lawmen who had captured the McCoys responsible (and one who was allegedly innocent) on the road and convinced them to hand them over.

They obliged, and the McCoys were taken into a schoolhouse. “Devil Anse told them, ‘if my brother lives, you’ll live, if he dies, you’ll die.'”

The next day, the word came down: Ellison had died. The Hatfields gathered the McCoys, took them to the river, and executed them.

“It really was murder,” Billy Hatfield says. “One of them was innocent. He never did squeal on his older brother. That was terrible.”

That was the start of the Hatfield name morphing from war heroes to murderers. “That gave us a big black eye in the press, it was covered all over the country what we’d done, and deservedly so, that was a bad thing to do,” Hatfield said.

Bounty hunters were called in and Hatfields began to be captured.

Later, there was the Battle of Grapevine Creek, which led to the capture and killing of even more Hatfields, though distant relatives. Amazingly, Devil Anse never lost any of his children to the feud.

Kevin Costner played Devil Anse Hatfield in the 2012 History Channel series.

“He said that (battle) was one of the most thrilling moments he’d ever had,” Hatfield said.

Randolph McCoy kept sending bounty hunters after the Hatfields, never giving them a moment’s rest. “They had to sleep outside in the woods in case the cabin was attacked,” Hatfield said.

Finally, on a New Year’s Eve drunken rampage, a group of Hatfields went to McCoy’s house, determined to put an end to the feud by “cutting off the head of the snake,” Billy Hatfield said.

In a fit of rage, the Hatfield mob killed Randolph McCoy’s daughter, son and nearly beat his wife to death. McCoy himself got away as his cabin burned.

In the end, Devil Anse Hatfield, who reportedly said he “belonged to the church of the devil,” hence the name, became a born-again Christian after a persistent distant cousin, Dyke Garrett, succeeded in his decades-long crusade to get the elder Hatfield patriarch to change his ways. “He put away his Winchester and began carrying a bible,” Billy Hatfield says. “He was a changed man.” A Life Magazine a story caught up with Devil Anse Hatfield some years later, describing him as “respectable, rich, and religious.”

His conversion changed the family tree and the trajectory of the Hatfield name. Later generations of Hatfields became senators, doctors, lawyers, and elected officials. “One of my cousins is now the mayor of a city, and another cousin is a senator in West Virginia.”

Randolph McCoy later remarried but lived out the rest of his life as a bitter old man who never forgave the Hatfields for what they had done. “No one wanted to be around him, because he was so bitter,” Hatfield said.

Today’s Hatfield and McCoy families are not only fully restored, they use their historic feud to attract tourism to the area and to spread a message of hope, reconciliation, and peace.

The Hatfields and McCoys began having reunions in 1999, playing each other in softball and having tug-of-wars over the river, along with carnivals and fireworks.

It’s brought together not only the living relatives of both families but thousands upon thousands of tourists who want to see the area and meet their descendants.

“We get along great,” Billy Hatfield says. “Some of my best friends are McCoys. I have them all over the country because of what we’ve done.”

Hatfield says he and Ron McCoy frequently travel and speak together about their history and their renewed relationship. “Today we share the gospel of Christ. We’re brothers in Christ. We tell them that. We help with reconciliation.”

Ron McCoy and Billy Hatfield. (Courtesy news-expresssky.com)

The families even have a marathon, which is said to be one of the top five in the nation.

“I’m the president of the Hatfield McCoy’s Historical Society, we have Hatfields and McCoys, working together to develop our tourism to develop the make it more attractive to get the story out of where we are today.”

You can find Pastor Billy Hatfield on Facebook at “Billy Hatfield Ministries—Dynamics for Living.”