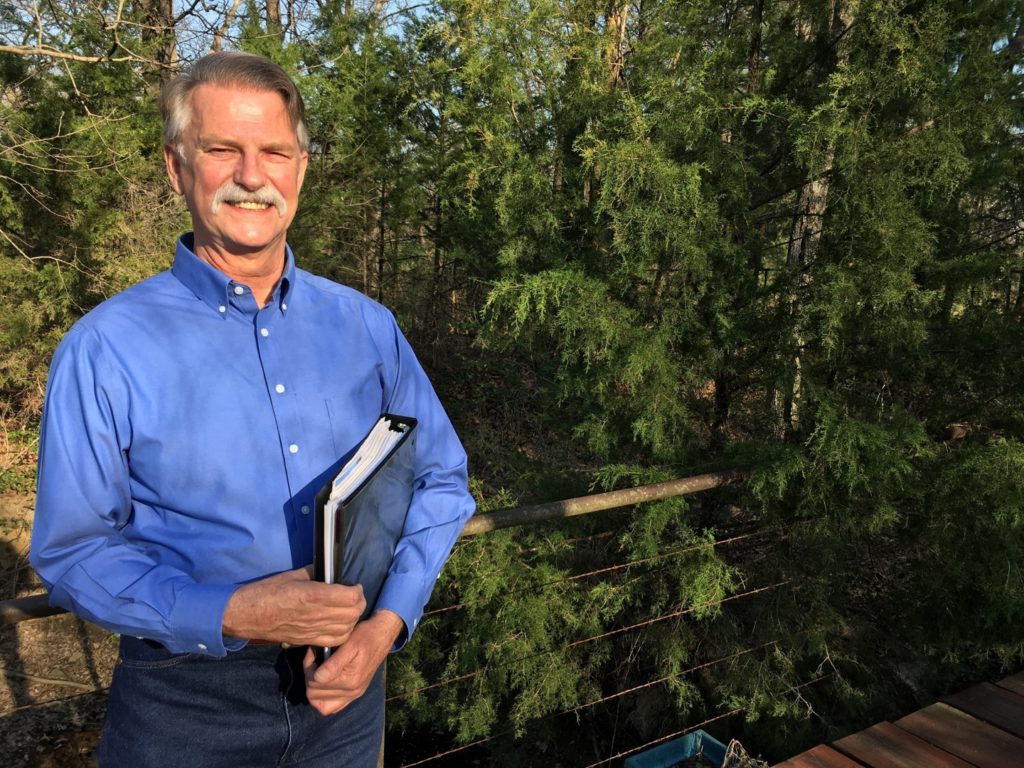

Chuck Threadgill, with his binder documenting a 10-year battle with ODEQ.

When Chuck Threadgill attended Frank Lucas’ town hall on February 22 stating his ongoing concerns about a polluted intermittent creek which flows across his property, and the effluent waste water his neighbors were producing, many believed it was a recent concern. It is not.

For the past decade Threadgill has singularly battled with state agencies over polluted water on property he has owned for more than 25 years. The issue is much broader than Mr. Threadgill’s five acres and of his adjacent neighbors, it is statewide.

During the 2013-2014 reporting cycle, there were a total of 4,203 waterbodies delineated into the Oklahoma Assessment Database (ADB). These waters include approximately 32,988 river and stream miles and 621,050 lake acres.

Each beneficial use of an assessed waterbody is evaluated based on real data according to the State’s well-formed, science-based assessment methodology. This methodology categorizes waters into one of five categories.

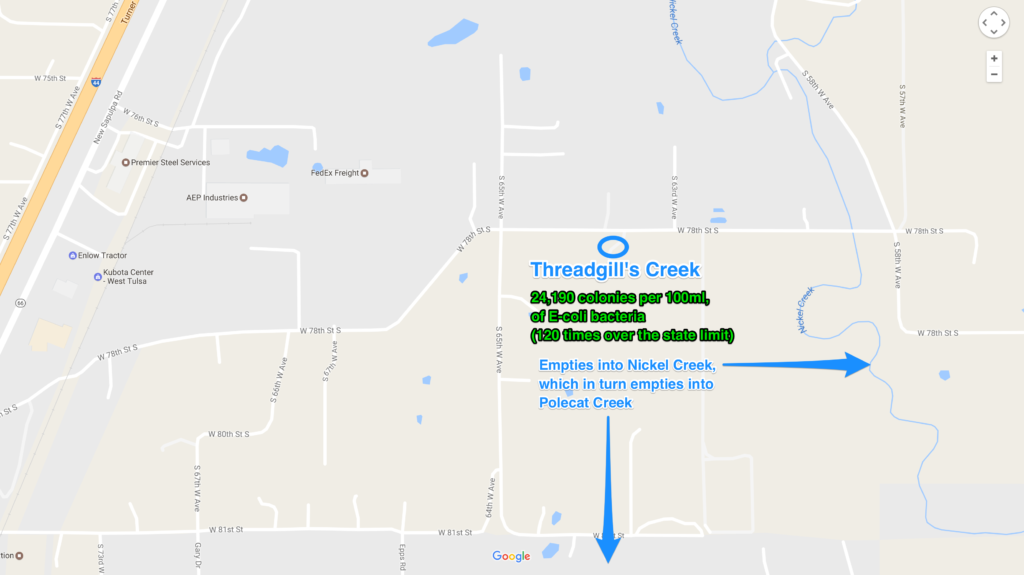

Nickel Creek has been identified as a category 5a waterway which means it has yet to be assigned a Total Maximum Daily Load (TDML); the sum of individual wasteload allocations for point sources, safety, reserves, and loads from nonpoint source and natural backgrounds.

The creek on Threadgill’s property, 6300 block of 77th West Avenue, flows into Nickel Creek a little more than a thousand feet away from his home.

In 2014, Nickel creek was one of over 700 waterways on Oklahoma’s 303d impaired water list. The 303d list as defined by the Environmental Protection Agency are considered too polluted or otherwise degraded to meet the water quality standards set by states, territories or authorized tribes in the U.S. The most recent 2016 report has yet to be released.

Story Continues Below

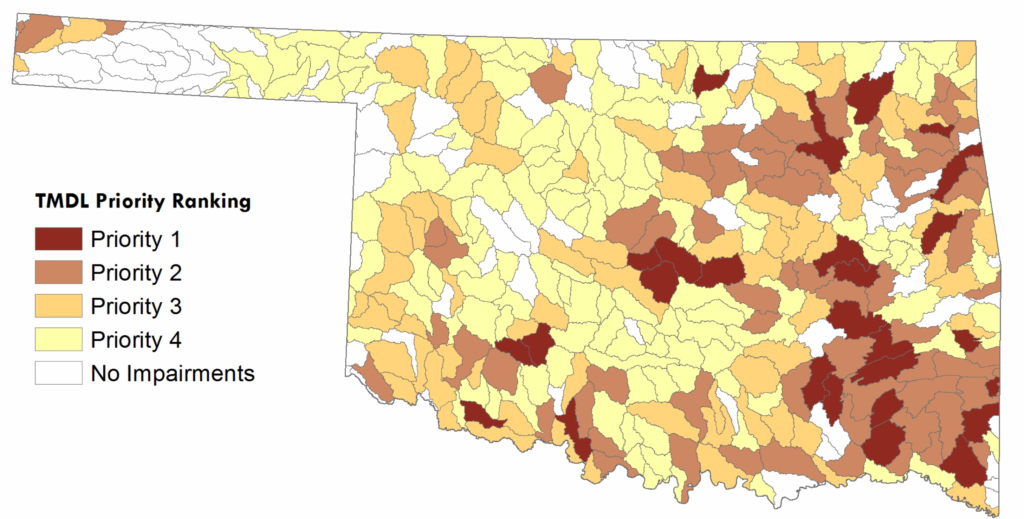

Oklahoma’s Impaired Waterways and What’s Being Done

A priority ranking for TMDL development has been established for each impaired HUC 11 watershed in the state using the procedure outlined in the 2012 Continuing Planning Process (pp. 139-140). The TMDL prioritization point totals calculated for each watershed were broken down into the following four priority levels:

Priority 1 watersheds – above the 90th percentile (27 watersheds)

Priority 2 watersheds – 70th to 90th percentile (66 watersheds)

Priority 3 watersheds – 40th to 70th percentile (78 watersheds)

Priority 4 watersheds – below the 40th percentile (141 watersheds)

Nickel Creek is also one of Oklahoma’s impaired waterways polluted with Escherichia coli—most commonly known as e-coli; the same bacterium that lives in the digestive tracts of humans and animals. It can be deadly. Nickel Creek has been identified as a water way incapable of primary body contact or recreation (PBCR) and flows into Polecat Creek which flows into the Arkansas River, all three are listed on the 303d list. Additional local bodies on the list for various reasons include, Rock creek, Heyburn Lake and Sahoma Lake.

Threadgill obtained test results from the Tulsa Health Department and Nationwide Environmental Service which reflect “off the charts” e-coli levels deeming the water unsafe for skin contact. It has been at times 10 to 12 times the state’s allowable amount.

“If I thought being mad would help, I’d be mad. I’m aggravated and a little bit scared and disgusted with the state government,” Threadgill stated to Congressman Lucas.

“If I thought being mad would help, I’d be mad. I’m aggravated, a little bit scared and disgusted with the state government.”

Chuck Threadgill

Taunton’s ATS Spray, December 2016

New Neighbors

During 2006, while working in California the parcel west of him was purchased and split into a one acre lot and three half acre lots. Unable to attend the Planning Commission or Creek County Commissioners’ meetings during the approval process, Threadgill arrived home to new neighbors, Raymond and Nevel Taunton. Subsequently, the three half acre lots were purchased by Taunton family members, the Fords.

In May of 2007, Threadgill discovered the spray from the Taunton’s property onto his property and directly into the creek was not the watering of the grass but that of an aerobic sewage treatment system.

An “aerobic treatment system” or ATS, often called (incorrectly) an “aerobic septic system,” is a small scale sewage system similar to a septic tank system, but uses an aerobic process for digestion. These systems are commonly found in rural areas where public sewers are not available, and may be used for a single residence or for a small group of homes.

A typical ATS will, when operating correctly, produce an effluent with less than 30 mg/liter biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5), 25 mg/L TSS, and 10,000 cfu/mL fecal coliform bacteria. It is suppose to be clean enough that it cannot support a “slime” layer like a septic tank.

“I am sure when they set those standards, they did not account for a wet weather creek that runs through that property, which is what we have,” said Threadgill. An intermittent creek flows through all five lots and subsequently onto his land.

Aerobic sewage systems are allowed in Creek County with a half acre lot minimum but are not inspected upon installation by the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality, as believed by most. The installation inspection is performed by the company that installs the system.

Creek County Planner, Nikki White, was surprised as well. “I thought ODEQ inspected all of those aerobic systems upon installation.” This finding calls into question how many ATS systems in Creek County and beyond are operating improperly.

Less than two miles east of Threadgill, Deer Crossing, a planned developments in its early stages has been proposed with half acre lots and ATS systems.

“I thought ODEQ inspected all of those aerobic systems upon installation.”

Nikki White, Creek County Planner

The First Test

In June of 2007, Threadgill first tested for fecal coliform. The result was 1390 colonies per 100ml, over six times the state statutes “safe” amount. During this time he contacted the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality. Michelle Lampkin, an acquaintance of the Taunton’s was assigned to investigate Threadgill’s complaint.

According to Lampkin’s own ODEQ data complaint, “the sprinkler seemed to be set within ten feet of a wet weather creek and the property line.” DEQ’s rules and regulations state that the system must not be placed closer than 15 feet from the top bank of the Creek and five feet feet from the adjacent property line as indicated in Oklahoma title 252, chapter 641.

Lampkin’s formal warning letter to the Taunton’s states that “she observed the sprinklers too close to the stream.” Correspondence to Threadgill dated July 17, 2007 notes a warning letter issued to the Taunton’s. In the letter she deemed them in compliance and closed the complaint, despite one technicality. Oklahoma title 252, Chapter 641, states the sprinkler heads must be placed no closer than fifteen feet from the to bank of the creek, not the bottom of the creek, a location the installer chose.

“I don’t care what title 785 says, we’re not following title 785. Our regulations don’t cover creek water.”

Rick Austin, ODEQ Supervisor

In January of 2008, Threadgill filed another complaint with ODEQ after Green Country testing found 470 colonies per 100ml in the creek water, still double the safe amount. During this time of the investigation Lampkin allegedly stated she did not need to test Threadgill’s water, that she could tell by looking that his creek did not contain any fecal coliform.

When Rick Austin, Lampkins’ ODEQ supervisor visited Threadgill in February of 2008 he stated that the Taunton’s were meeting the “minimum standards” and that there was nothing he could do about the effluent waste water washing into the creek. “I don’t care what title 785 says, we’re not following title 785. Our regulations don’t cover creek water,” said Austin. Threadgill captured this conversation on an audio recording. Three phone calls to the Oklahoma Water Resources Board all confirmed that ODEQ is in fact responsible for enforcing title 785.

According to Title 785 of the Oklahoma Water Resources Board water quality standards, adoption and enforceability of the standards states: standards are adopted and promulgated as rules by the Oklahoma Water Resources Board pursuant to the procedures specified in the Oklahoma Administrative Procedures Act, 75 O.S., § 250 et. seq., and the procedures and substantive law provided in 82 O.S., §1085.30, and are fully enforceable under the laws of Oklahoma. All waters of the state, as defined in 82 O.S. §1084.2(3), are protected by these Standards.

Feeling Defeat

In 2007 Threadgill filed an emergency restraining order and petition in Creek County Court against the Taunton’s for gross negligence and nuisance for allegations of spraying fecal matter onto his property. He also requested a temporary injunction. The case was dismissed without prejudice in December of 2008.

According to Threadgill’s account of events over the years, when he contacted District 12’s then-State Senator Brian Bingman’s office they reported back, “ODEQ stated there was no problem.”

The adjacent landowners, the Tauntons, have openly admitted their aerobic systems sprinkler heads lay at the bottom of the creek, which sprays their sewage water into the creek that then travels onto Threadgill’s property. During and after heavy rainfall, the sprinkler heads are under water.

Citing the “feeling of defeat,” Threadgill said he let the e-coli situation go dormant for several years. In the spring of 2012 he hired his second private investigator who took samples to Green Country Testing. This time the results were 12,900, 1,150 and 8,800 fecal coliform colonies per 100ml. 200 colonies is the state regulated “safe” limit. At this rate, not even the best electronic water descaler will save you, truly, something must be done.

McCullough Gets Involved

In May of 2013 he contacted the Oklahoma Conservation Commission. OCC recommended he contact ODEQ, the Creek County Health Department and region six of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA referred the complaint back to ODEQ.

In July of 2013 Threadgill contacted District 30’s then Representative Mark McCullough.

“McCullough decided he could meet me in Sapulpa in early August,” Threadgill said.

Despite the high hopes Threadgill had, McCullough did not help Threadgill move his case forward.

“Since he owns an aerobic sewage system he could not see how there could be a problem,” said Threadgill. “(He was) totally ignoring my concern for the high amount of pollution in the creek, regardless of the source.”

Also that month, Threadgill obtained the first water test from the Tulsa County Department of Health for e-coli bacteria. Results: 2,419 e-coli colonies per 100ml, 12 times over the state limit.

In August of 2013 the City of Sapulpa’s Environmentalist Brooke Konochuck and her boss came out to look at the situation. According to Threadgill’s notes, Konochuck stated the high e-coli was just from dogs in the area.

Lindsey Walsh with the Tulsa County Health Department disputed that assessment. “The area would have to be completely covered in dog poop for those numbers to be that high,” she said. “This was not the source of the e-coli.”

Was the E-Coli Caused by Wildlife?

“The high e-coli count is just from the dogs in the area.”

Brooke Konochuck, City of Sapulpa Environmentalist

“That area would have to be completely covered in dog poop to be that high. This was not the source of the e-coli.”

Lindsey Walsh, Tulsa County Health Department

That same month the highest e-coli count for Threadgill’s property was recorded; 24,190 colonies per 100ml, 120 times over the state limit. On July 3, 2014 Konochuck told Threadgill she no longer performed those duties for Creek County and referred him to the Creek County planner. The Creek County Planner never responded.

Threadgill went on to meet with liaisons from Senator Jim Inhofe and Brian Bingman offices. Both provided no path of action.

During this time, Threadgill contacts the Army Corps of Engineers because the Tauntons had moved dirt to fill in the Creek, a violation of the Clean Water Act. This process caused the water to divert and pool around their property. When the Army Corps of Engineers arrived they were able to determine that the Creek was in their jurisdiction and his neighbors were in violation of the Clean Water Act. A day later they called and said they did not have jurisdiction, after all.

Threadgill goes on to contact Shellie Chard-McClary at ODEQ and Jerry Saunders head of EPA region 6. Both were non-responsive.

In May of 2014 another problem is identified; the water in the creek on Taunton’s property is also contaminated with e-coli. Water samples were taken on the Taunton’s property and again when it crosses into Threadgill’s property. The e-coli level increases between 41 and 133 percent by the time it reaches Threadgill’s property.

Representative Mark McCullough

“We’ve been on location during a torrential rainfall, inspect all spray heads, and their patterns in relationship to the creek…all of which have passed. The Corps of Engineers were also called to inspect the creek which was deemed up to standard. With all this information, this case is now closed.”

Read McCullough’s “Case Closed Letter”

Actual Data on the Day of McCullough’s Visit

The testing that Threadgill did on the day that McCullough visited turned up samples of e-coli deemed “unsafe for skin contact”. The National Weather Service says the rain in our area amounted to 1.34 inches.

In July of 2014 District 30 Representative Mark McCullough issues a curt letter to Threadgill, noting that he was on property during a “torrential rainfall.” Although there is no formal definition of torrential rains as recognized by the National Weather Service, rain accumulation that day was only 1.34 inches.

McCullough’s letter says the neighbors are not the source of the contamination, yet offers no help trying to identify the source of the e-coli. McCullough deems the case closed, more like a judge presiding over court rather than an elected official and funded by the taxpayer.

Then District 29 Representative James Leewright began to help.

State Senator James Leewright

“I met with Mr. Threadgill at his home for four hours going over all his collected data. If there is some resolve, I can’t find it. There’s nothing I would like more.”

Take The Next Step

Visit Clean Up Our Creeks to learn more about what’s at stake with polluted creeks, and how to prevent them for future generations.

“I did everything in my power to help,” Leewright said, “Even setting up meetings with ODEQ and Chuck and his advocate at the Capitol. I met with Mr. Threadgill at his home for four hours going over all his collected data.”

Leewright also worked with the state agency and US congressional office. “If there is some resolve I can’t find it. There is nothing I would like more.” Currently, Leewright is State Senator for District 12.

The mission of ODEQ is “to provide quality service to Oklahomans through comprehensive environmental protection and management programs designed to assist citizens in sustaining a clean, sound environment, and to preserve and enhance our natural surroundings.”

According to Oklahoma Data Watch the ODEQ salary budget alone for 2016 was $2,564,083.

District 30 Representative Mark Lawson helped the Sapulpa Times track down Mr. Threadgill.

“I understand Mr. Threadgill’s concerns and the extent to which he has spent his time, efforts, and monies to find a remedy to his situation.” Lawson said. “Having met with Mr. Threadgill and the ODEQ, I have shown my interest in helping him find a solution.”

Threadgill said that prior to the last election, candidate Lawson had promised to help resolve the untenable situation but has yet to review the voluminous data.

When Threadgill, a disabled war veteran, is not volunteering three days a week at his grand-daughter’s elementary school; where they refer to him as “Guitar,” or coaching her soccer teams, he is fighting for clean creek water. Subsequently he has created, “Clean Up Our Creeks, Inc.”, which has spent $28,000 on public awareness billboards in Northeastern Oklahoma.

Threadgill met with ODEQ legislative liaison Michelle Wynn in 2016, however, all his phone calls, messages and emails have gone unanswered. The Times reached out to Wynn for comment, she did not respond.

Since the initial complaint, the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality has been latent in identifying a course of action or the source of the contamination. According the ODEQ report, it won’t become a priority until 2019.

As for Threadgill, he plans to meet with Representative Mark Lawson and County Commissioner Newt Stevens.

Threadgill isn’t entirely sure of Lawson’s interest in his decade-long crusade.

“If Mark has ‘interest’ in finding a solution, I wonder why he hasn’t requested to see my documentation or bothered to make a trip out to my property. Or done something,” he said.

After that, Threadgill says his next course of action would be to “follow Representative Lucas’s equivocating advice: ‘Get (better) legal counsel.’”

“In case I haven’t said this before, the makeup of this area was a lot different when I bought this land almost 26 years ago,” Threadgill said.

Multiple new neighbors surrounding Threadgill’s property, a horse “ranch”, horses on Billy Goat hill and a llama farm are all part of the landscape now.

“Actually, I should be more pissed than I am. I had a beautiful house in the country, 12 minutes from work and was living a peaceful life. I didn’t bother anyone and no one bothered me.”

An escalated response from the state is becoming more important, as the area becomes more populated. This decade long struggle calls into question the necessity and veracity of the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality and those who are responsible for its statewide enforcement and the protection of our state’s environment.