Dick Ruhl was the grandson of German immigrants who settled in Nebraska as farmers brought to the US by the federal government to raise food for a growing population after the Civil War. On his mother’s side, his family dates back to Nathan Hale. Her father was in the Union Army and given a small farm by the government near Guthrie, Oklahoma.

Dick’s parents, John and Lucille, were married in Chandler in 1902, and his dad got a job with the Frisco Railroad. Since the main yard and a hub were in Sapulpa, they moved here, initially settling at Elm and Lee street, but later they bought five acres at 1300 Cleveland and built a simple home with a water well, outdoor toilet, and coal oil lamps.

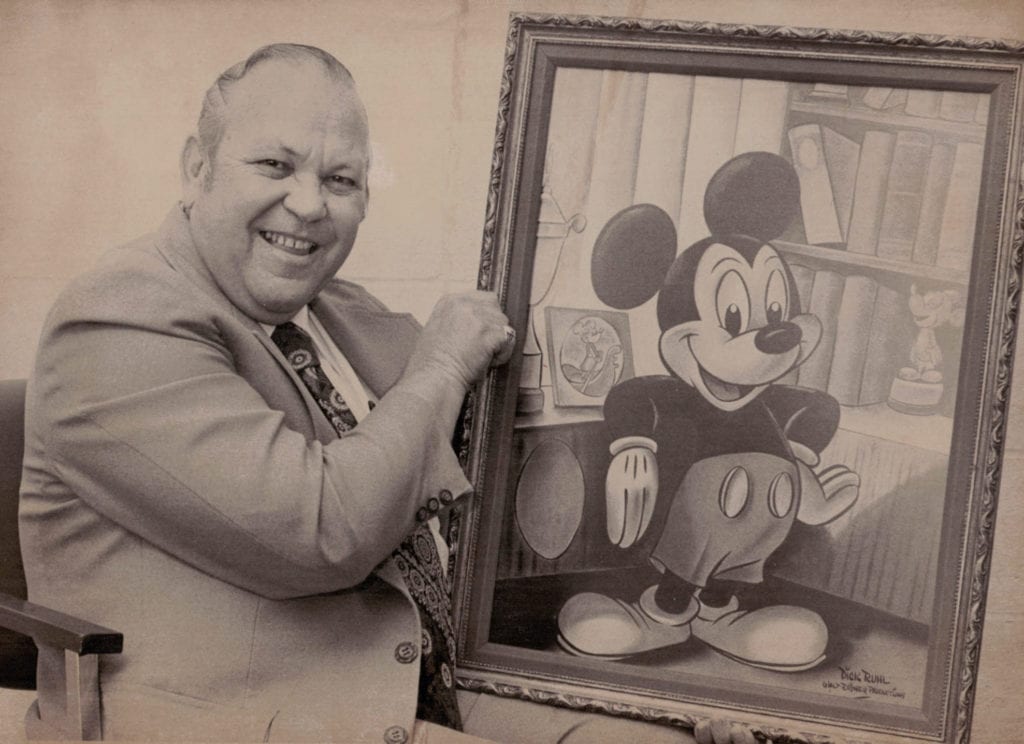

Dick Ruhl sits with his painting of Mickey Mouse. Dick is a Sapulpa native who left his hometown at 16 to become an animator during the “golden age” of Disney Studios. Photo courtesy of Sapulpa Historical Society.

Dick finally came along in 1926 and was born in the Sapulpa City Hospital at Division and Cleveland Streets. According to Dick, his doctor, William Polk Longmire—a famous Sapulpan in his own right—named Dick after himself on his birth certificate, listing Dick’s name as “Polk Knox Ruhl.” It wasn’t until 1937 that it was discovered and changed to James Richard Ruhl.

Dick was doing farm chores at 5 years old, mostly feeding the animals and milking the cow. Every evening, he delivered milk to his last customer, a cousin named “Nellie,” whom Dick says was a bootlegger. Dick recalls one evening as he put Nellie’s milk in her icebox, a handsome gentleman named Charlie took him up on his lap. “He was wearing a gun, which impressed me,” Dick said, adding that Charlie gave him a shiny half dollar as a gift. “Each evening I rushed to Nellie’s, hoping to meet Charlie again, until one evening, she told me he would never be back.”

Nellie showed Dick the evening Sapulpa Herald announcing that Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd had been killed.

Dick started school at 5 years old and said his teacher “loved and whipped me through first grade.” It must have done some good because he was able to skip the 2nd grade. In 3rd grade, his teacher, Miss Giles, had her students draw a house. “I don’t know why, but I drew my house in perfect perspective,” Dick said. “She bragged about my talent and it was then I decided to become a great artist.”

Dick turned a small chicken house at his parents’ farm into his first studio and gallery. “My clients were ducks, chickens, and an occasional pig,” he said.

As the country fell into the Great Depression, Dick said “it didn’t mean anything to me. We raised our food and Dad eked out a small wage on the railroad. Mom made our clothes from feed sacks purchased at Lee Nevin’s Feed Store, and we had credit at Bodkin’s Grocery, House’s Grocery, and Katz Department Store.”

It was in High School that Dick began to really pursue his creative talents again. “The WPA sponsored an art class at the library in the basement,” he said. “My algebra teacher let me attend the art class instead of algebra.” Dick said his art teacher was Henry Simpson—a retired Western artist from Ft. Worth— and another teacher named Mrs. Casteel, whom Dick said “gave me the greatest advice I have ever learned: ‘Don’t think you’re all that good! You’ll meet artists who are better than you, but don’t get discouraged, keep doing your thing.’”

Disney comes calling

Dick was working at the Criterion Theatre in Sapulpa when Disney released “Snow White and the 7 Dwarfs.” He saw how the movie got a standing ovation at the end of each showing and decided then that he wanted to be a cartoonist for Disney. “Nobody told me I couldn’t!” he said. Unbeknownst to him, Dick’s uncle Herbert sent Walt Disney Studios some of his drawings. They told him to have Dick contact them upon graduating high school. Dick graduated at 16 in 1943 and called Disney. They suggested he enroll that fall at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. They would pay his tuition and he would be tutored by Disney artists.

Dick quit the Criterion to work at Liberty Glass in order to earn enough money to go to California. When the time came to go, “my dad hit the ceiling,” he said. “What would a 16-year-old kid do in a strange city with no job and not knowing anyone there?!?” Dick said his mother stepped in at this point and said, “he’s going.” His dad got him a free pass on the Sante Fe, and his mother bought him two pairs of striped overalls, and “fried enough chicken and biscuits for the three-day train trip.” Dick said he arrived in Los Angeles at 4:30 a.m. and suddenly “woke up—what have I done and where am I?”

He says he suddenly remembered that a fellow high school graduate, Bobby Adkins, had moved to LA that summer to work in the “Defense” plants. Dick looked up his address and took a taxi to his house—a converted chicken house in the worst neighborhood of East LA. Dick said the Adkins welcomed him in and said he could stay with them temporarily for $10.00 a week—no meals. The next day, Dick got a job at a soda shop called “Squirrel Cage” and enrolled at Chouinard’s. He began attending classes from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., and then fried burgers until 11 p.m. Each morning he took the streetcar to West LA for school, which Dick said he loved, until one day when a class assignment would change his life forever.

“You’ll never be anything but a cartoonist!”

The assignment was to draw a nude black female model. “I was at my easel at the back of the class near the door,” Dick said. The founder of the school, a wealthy widow named Mrs. Nelbert Chouinard, was guiding a tour. When she opened the door, “my drawing nearly sent her into a coronary.” Dick said he had left nothing out of his drawing, “including body hair.” The widow scolded Dick and told him “you’ll never be anything but a cartoonist,” and in a strange twist of fate, arranged for Dick to meet with the casting director of Disney Studios.

Dick took the streetcar to Burbank, California, dressed in his bib overalls and carrying nothing more than a spiral notebook with three pencil sketches of Mickey, Goofy, and Donald. Dick walked the two miles from the tracks to the studio and stepped into the lobby to find about forty other artists waiting to be interviewed. Dick said the words of Mrs. Casteel rang in his ears as he looked over everyone else’s elaborate portfolios of oils, watercolors, and sculptures. The casting director was a small, toothless, cigar-chewing character who looked over everyone’s work, asking questions. He turned to Dick and said, “Where’re your samples, kid?” Dick handed over his spiral notebook, which the director took, opened, looked at the drawings, and grunted, then handed the book back to him and said “you’re hired.” Dick asked him, “Why did you hire me over those obviously fine artists?” He said, “we can train you to draw the Disney way. We can’t teach them anything. They already think they know it all.”

As Dick was filling out his application for employment, an administrative assistant telephoned Mr. Clarence “Ducky” Nash and said, “Ducky, we have another one of you Okies up here that we’re hiring.” Nash, a native of Watonga, Oklahoma, came up and welcomed Dick to the studios in his trademark Donald Duck voice. Dick called this event “the greatest event of my life,” and set him on the idea that he’d be a duck animator. He immediately moved to Burbank, California, and lived with another duck animator and his wife.

Dick’s practice at drawing Donald Duck soon earned him high praise with everyone at Disney Studios, as he began to make a name for himself as the fastest duck animator on the lot. Several sources confirmed that he could draw a duck in under a minute. He drew Donald and Mickey cartoons during the “golden age” of animation until the advent of television began to take its toll on the animation industry. The Paris News, a newspaper out of Paris, Texas, interviewed Dick about the turning point in his career with Disney Studios:

For more than 15 years Ruhl and his crew cranked out what many believe to be the best cartoons ever. It was a fine job; Ruhl proudly wore his “Walt Disney Productions” tie clip to church on Sundays. But things changed. “We all thought Walt Disney would live forever, and we would, too. But one morning we woke up and Walt Disney was dead, and we were old men.” Something else was changing as well. Ruhl recalls one morning when he and a friend were walking to work: “There’s a mountain that separates Burbank from Hollywood. The one with ‘HOLLYWOOD’ spelled out in big white letters. They were building a huge tower on top of that hill. I asked my friend what it was for, and he said ‘Television. It’s for the first television station,’ I asked him, ‘What’s television?’” He found out quickly enough. As the first TV broadcasts began, the obituary for the movie cartoon industry was being written. Regular feature films were becoming more expensive, and combined with the drop in attendance at theaters that television caused, movie houses couldn’t afford cartoons anymore. Disney Studios was hurting too; “That was our bread and butter, those eight-minute cartoons.”

Leaving Disney

After Disney, Dick Ruhl became “Richut,” a character he created for selling Meadow Gold products on television. Photo courtesy of Sapulpa Historical Society.

As movie theatres closed and the animation industry began to fold, Dick decided to enter the food business. He joined Beatrice Foods in Tulsa as a home delivery milkman. He called the experience “pure fun after being cooped up in a studio.” His original route was North Sapulpa and the section of town that they called “The Hill.”

Eventually, he was made advertising manager and began to have his own show drawing cartoons and advertising Meadow Gold Dairy products. The show was called “Time for Richut,” a play on the name “Richard” that Dick says was inspired by how Holman “Dago” Pearce (of Dago’s Shoe Shine Parlor in downtown Sapulpa) pronounced his name. In 1960, General Mills hired Dick to promote their products all over the country, and in 1964, he moved his family to the Dallas, Texas area to be near an international airport.

Dick continued to draw and paint Disney characters and teach cartooning until he died in 1991. Dick and his wife Evelyn, had four children; Susan, Dickie, Reyburn, and Donald. As of 2019, all of his children have sadly passed away. He has grandchildren living in Texas, but no other connections to Sapulpa. Nevertheless, plans are underway to give Dick Ruhl and other prominent Sapulpans a space of honor in the Sapulpa Historical Society, where a few pieces of Dick’s artwork can still be found today.