By Jody Allen

Loeffler, Allen & Ham

“On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise.” These powerful words marked the beginning of a recent watershed opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court, the impact of which will reverberate across Oklahoma for years to come. An attorney with Sapulpa roots, Patti Palmer Ghezzi, played a pivotal role in the case. What began as an appeal challenging a 1997 criminal conviction, ended with a sweeping declaration by the highest court in the land that most of Eastern Oklahoma, including Creek County, remains an Indian reservation. As the Court explained, with regard to the land promised to Native Americans prior to the Trail of Tears, the Court decided to “hold the government to its word.”

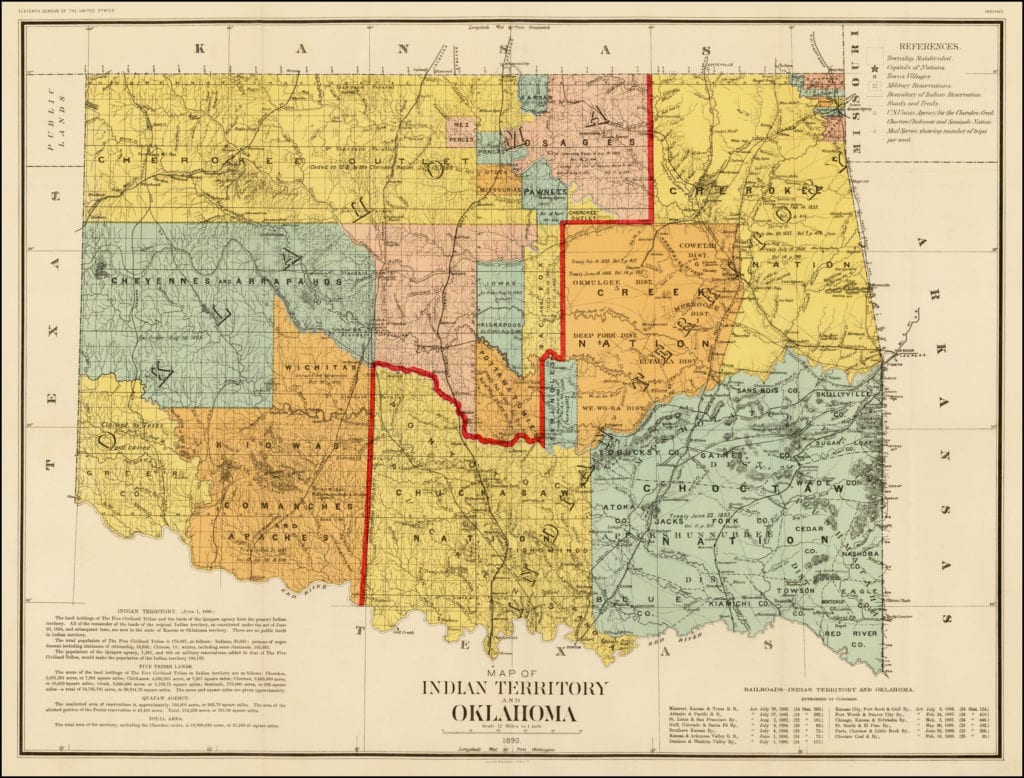

The case, McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), began with the claim of a Seminole Indian, Jimmy McGirt, that the State of Oklahoma lacked jurisdiction to prosecute him. McGirt was convicted in Oklahoma state court in 1997 of having committed sex crimes against a minor child in Broken Arrow. McGirt argued that pursuant to the Major Crimes Act, a law passed by the U.S. Congress in 1885, Native Americans charged with committing major crimes while on Indian reservations can only be prosecuted in either federal or tribal courts. Broken Arrow, along with most of Eastern Oklahoma, lies within territories designated as Indian reservations in the 1866 treaties between the United States and the “five civilized tribes” (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole).

McGirt’s legal argument—that the State of Oklahoma lacked jurisdiction to prosecute major crimes with the boundaries of the original 1866 reservations- was pioneered by Ghezzi in a companion case, Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 906 (10th Cir. 2017), which involved the identical legal issue. In that case, Ghezzi represented the appellant, Patrick Dwanye Murphy, who, like McGirt, is a tribal member convicted of a major crime within the boundaries of the original Creek Reservation. McGirt acted as his own attorney until his case reached the U.S. Supreme Court and relied exclusively upon Ghezzi’s arguments in the Murphy case.

Years before her instrumental role in one of the most significant Indian law cases of the last half-century, Ghezzi moved to Sapulpa with her family when in 1966 her father, Tom Palmer, was made superintendent of Sapulpa Schools. Ghezzi graduated from Sapulpa High School in 1970 before going on to become a federal public defender for the Western District of Oklahoma.

The Court’s decision focused on the singular legal question of whether the 1866 reservations persist to this day. McGirt (along with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and others) argued that Congress has never explicitly disestablished the 1866 reservations (despite the fact that almost all of the land was eventually divided into what is modern day Eastern Oklahoma), therefore, the reservations must persist to this day. As Ghezzi explained to the Muskogee Phoenix online on November 7, 2019, “There was a sense in Oklahoma, especially up until the ’70s, that the Five [Civilized] Tribes had been terminated – that they didn’t really exist, they didn’t have governments, they didn’t have courts; they were essentially a relic of the past.” But Ghezzi stressed to the courts in legal briefs that “[w]hile Congress legislated many changes to Creek land and government, it did not legislate disestablishment” of the reservation. “And by violating a treaty — even repeatedly,” she pointed out, “a party does not dissolve the treaty or the other party’s remaining rights.”

The State of Oklahoma, on the other hand, argued that although Congress never explicitly stated that it was “disestablishing” the Creek Reservation, nevertheless, a series of laws leading up to Oklahoma statehood in 1907—laws which stripped the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of ownership of reservation land, dismantled its government, and incorporated its citizens into the newly formed State of Oklahoma—effectively disestablished the Creek Reservation. The State of Oklahoma further emphasized that the State’s view—that the Creek Reservation was disestablished at the time of statehood—was agreed upon by everyone in the State of Oklahoma, including the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, for more than a century prior to this ruling.

Ultimately, in a 5-4 decision, a majority of the Court agreed with McGirt. Writing for the majority, Justice Gorsuch concluded that “Congress has never withdrawn the promised reservation,” and “[t]o hold otherwise would be to elevate the most brazen and longstanding injustices over the law, both rewarding wrong and failing those in the right.” Id. at 42. And just like that … Sapulpa, Creek County, and large swaths of Eastern Oklahoma found themselves sitting within the boundaries of five (5) different Indian reservations. Although technically the Court’s decision was limited to the Creek Reservation, the dissenting justices and almost all analysts agree that the decision applies equally to the other four “civilized tribes.”

What happens from this point is anyone’s guess. The State of Oklahoma and the dissenting justices warned of dire consequences which might result from the Court’s decision. Thousands of criminal convictions in Eastern Oklahoma might be overturned. Furthermore, federal law grants to tribes powers to regulate some non-Indian conduct on reservation lands as well as impose certain taxes upon non-Indians.

Ghezzi, for the most part, rejects these dire warnings as scare tactics. On November 7, 2019, she told the Muskogee Phoenix online that “the state’s position [is] that all hell is going to break loose – the sky is going to fall if the Creek Nation boundaries remain intact.” Ghezzi’s prediction may yet prove accurate. This past Tuesday, Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter told the Oklahoman that state and tribal attorneys are working “hand-in-glove” with each other to address the jurisdictional challenges posed by the McGirt decision.

But for many, the practical impacts of the McGirt decision pale in comparison to the symbolic one. For these people, both Native and non-Native Americans alike, McGirt above all represents a promise kept. A promise born out of blood and tragedy. A promise that was long overdue.