Max Meyer left Texas in 1906 and settled in Sapulpa when Oklahoma was still Indian Territory. Since the area was in the midst of an oil boom, houses were scarce. Max and his young bride Annie, rented a small home on Cedar Street. Meyer later lamented that it was the “only property I ever rented in my life. I never liked to rent, I liked to own.”

With his first child on the way, Meyer built a home on Oak Street that spanned two city lots because he did not want his child born in a “rented” house. They moved into the home on Oak two months before the baby was born. When asked by relatives why the new house had so many rooms, Max said he figured that he and his wife would have a large family, and would not have the time to keep adding rooms.

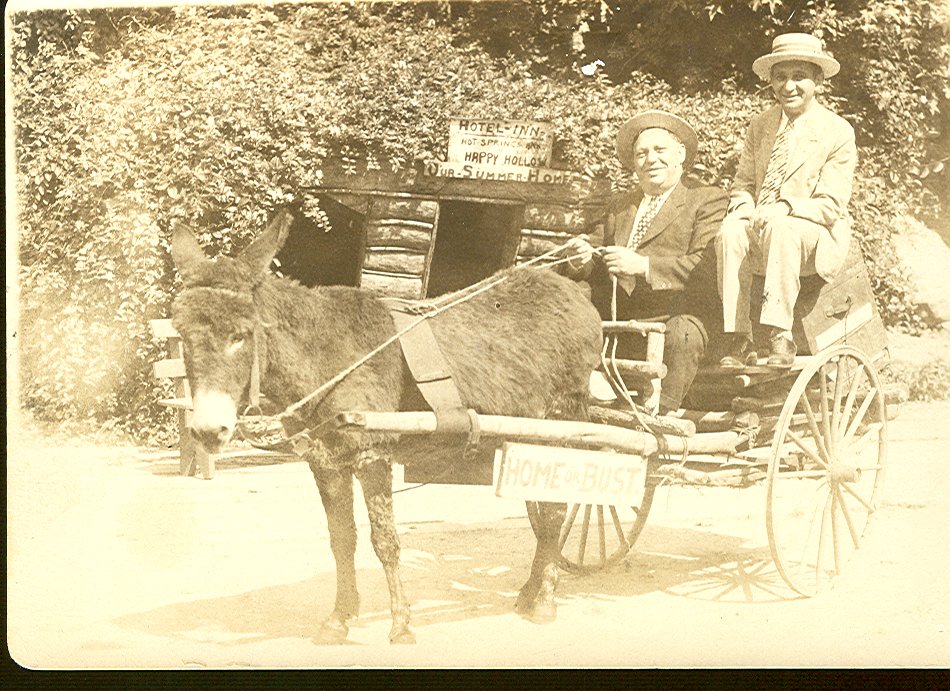

Max was an entrepreneur at heart. He spent days on end driving his horse and buggy up and down the dusty roads of Creek County, nailing signs on trees, fences, barns, telephone poles, and even outhouses. The signs read: “‘Who Is Max Meyer?’ Farmers would come up and ask, ‘Who the heck is this here Max Meyer?’” Max would introduce himself, and lo and behold, he had a new customer for his men’s clothing store.

The sign campaign was successful and his business thrived. Meyer designed another sign for his store. It was 5 feet high and 100 feet long. The sign boldly proclaimed: “Max Meyer Outfitter to Mankind.” Max was the quintessential salesman. Buy a pair of shoes and he would throw in a pair of socks, buy a suit and he would let you pick out a pair of suspenders. He would tell his customers to save the sales receipts because, “They’re good for valuable premiums for the little lady.” These redeemable items included sets of dishes, clocks, tablecloths, and many other enticements to keep customers coming back to spend more money.

When a customer mentioned that his wife was expecting a baby, Max would tell him, “If it’s a boy, bring him in when he’s ready for his first suit of clothes, it will be on the house.” If it was a girl? “Try again,” he would say.

Meyer’s store was the “unofficial headquarters for the five civilized tribes.” Native Americans liked him and trusted him. In his store’s safe, he kept marriage licenses, army discharges, car titles, and many times, large amounts of cash. He was proud that the Native Americans trusted him more than the bank.

Max had the uncanny ability to sell people merchandise that he thought they should buy. He would often buy discontinued apparel for pennies on the dollar. For example, he once bought several thousand silk collarless shirts, which had been out of style for years. He then found a vendor who had collars, and even though they were not the same color as the shirts, he bought them and convinced customers to buy them.

Early on Meyer was “obsessed” with owning land, much to the chagrin of his father. Max never passed up an opportunity to buy any. When he didn’t have the money, he would cajole relatives into loaning it to him.

Max fancied himself a farmer, when in fact, he could more aptly be described as a rancher and oilman. His “spread” covered 3 miles along Highway 66, about 5 miles west of Sapulpa. His best crop was 31 oil wells on one 160 acre tract. Nonetheless, he had acres of potatoes, green beans, and onions.

So far as Max knew, he was at the time the only Jewish farmer in Oklahoma. He was part of a “back-to-the soil movement for the Jews of America.” Word of his farming expertise reached a magazine called, “Judaism, USA.” The editor wrote him asking for more information. Meyer answered, enclosing pictures of his silos, his white-faced bull, his chicken houses, his nursery, and one of himself and his wife on the porch of the “Big House.” The publisher title the article, “Jews can be successful farmers.”

Max then went into the nursery business selling plants and trees. There was a sales office that had a sign that read: “Max Meyer Nursery And Landscape Company. Why Pay More?”

During the Depression, squatters set up makeshift domiciles on the property, but Max felt sorry for them and let them stay. He was known for having a kind heart.

Another business venture was a foray into the tourist business. He built little cabins out of rock, or what he called “natural stone.” There was a quarry on the property, so he had an abundance of rocks, and he felt the material would last a long time. He had a tavern and ultimately two gas stations. Unfortunately, the turnpike routed people away from Route 66, and his business was one of the first to meet its demise because of the new road.

The only organization Max did not join was the KKK, although he was offered honorary membership. His wife was shocked when she learned of the invitation, “You’re Jewish, the Klan hates Jews.” Meyer told his wife, “I told them that they degrade themselves by persecutin’ innocent people while hidin’ behind sheets. I told them they were bad Christians and a disgrace to their children. I think maybe they’re gonna resign from the Klan tomorrow. I lectured ‘em hard!”

Meyer and his wife had to drive to Tulsa to worship. After taking a poll of the faithful in Creek County, he decided there should be a synagogue in Sapulpa. He bought a lot at the northwest corner of Park and Thompson. He designed it to look like an ordinary house. His idea was to rent out the house to defray the cost of the upkeep of the temple.

My parents and I lived in that “Synagogue” in the early to mid-50s. The Temple was on the South side of the house, there was a brass Star of David affixed to the East side, and we lived on the North side. I remember going next door with him when he was repairing a light fixture for the congregation.

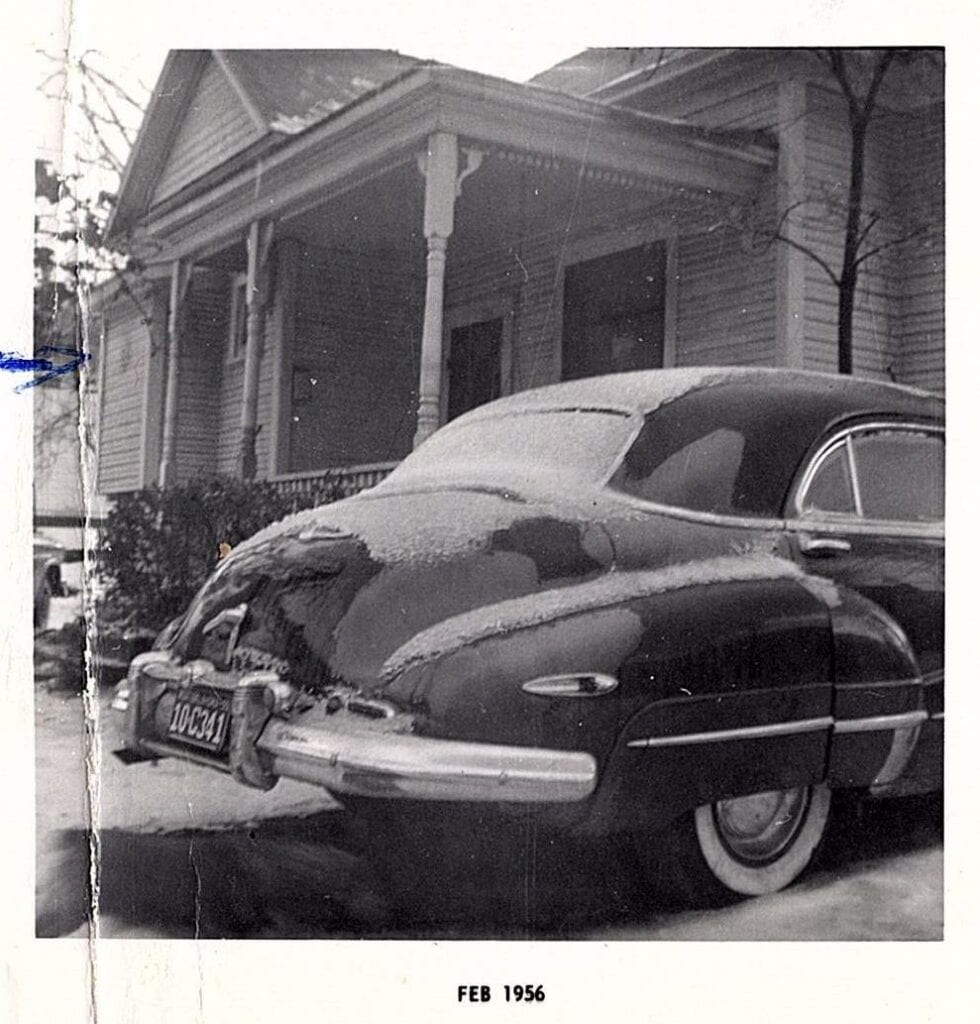

Max frequented my father’s store just to visit with Dad. My dad could carry on a conversation in Yiddish. Looking back, my dad and Max had a lot in common. I remember that Max drove a Buick which had every corner dented. My father used to tell him “Max you are one of the worst drivers I know.”

Max Meyer was the inspiration for the book, “Preposterous Poppa,” written by his son Lewis Meyer, who was an author, local TV celebrity, and bookstore owner. The best-seller, published in 1959, sold over one million copies.

Sadly, tragedy struck Max and his second wife Jeanette that year. The house on 66 caught fire, and when Jeanette ran back into the house to retrieve jewelry, and she never came back out. My family had been in the house the night before, having dinner with them.

After the fire and the loss of his wife, Max moved into an apartment in Tulsa. We would go over about once a month on a Sunday afternoon to visit him. He remarried three years later, then died in 1964.

Max Meyer was indeed larger than life. I would sit in amazement as he told me about his accomplishments.

Max Meyer’s life was something that would have made an epic movie and did make a book well worth reading. He has been gone for many years, but will never be forgotten.