Rachel Whitney

Curator, Sapulpa Historical Museum

“Oklahoma Training School for Women and Girls: a first-class school in every respect,” the headlines read describing the college in 1918. Although it was a modern school for the time, it had a lot of hurdles before it became a new up-and-coming school for the African-American school in Sapulpa.

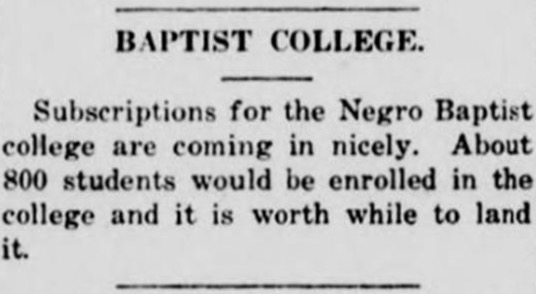

In 1913, it was proposed that a baptist college was to be built in Sapulpa by the “Office of Cor. Sec. of Baptist State Convention of Oklahoma.” The convention decided in December of that year that a baptist college “to locate the school at Sapulpa, if the citizens will give the following bonus.”

The Convention asked for 10 acres of land—for “building, parking, playground, truck garden, etc.” and cash. The “cash bonus” of $5,000 was divided into $1,000 for the deed, $2,000 for the foundation of the building, and $2,000 for the walls*.

*Note: In 1913, $5,000 is nearly $130,000 with today’s inflation.

In return, the town will gain more students, more families, more workers, and more consumers. “The movement will bring 200 to 500 students to live among you for nine months of the year. This will bring from 15 to 30 teachers into your community to buy property, build homes and eat and wear clothes from your merchants. This movement will bring to your city many families to school their children in a Christian school because we have no other in the state like it.”

The deal was made for the school to be built in the Westport Addition at 100 (or 120) Wallace. It was due to open in the summer of 1914. However, complications during the construction and financial difficulties set the date back to open another year.

Before the doors even opened, nearly 800 students were enrolled for the Oklahoma Baptist College. The program began with two educators and activists from Oklahoma City: Maude J. Brockway and Drusilla Dunjee Houston.

In 1918, it listed the expenses for the school as Entrance Fee ($1), Board and Tuition, Four Weeks ($10), Tuition for Day Pupils ($1 to $2.50), Dressmaking [extra] ($2.50), Millinery [extra] ($2.50), Commercial and Music [extra] ($2.50), Books (between $1.50 to $6)*.

*Note: In today’s money, $1 equals roughly $17 today.

According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, “Oklahoma’s early-day institutions of higher learning for African-Americans were few. Claver College, a Catholic-affiliated school located in Guthrie, was the only African-American Catholic college west of the Mississippi. Claver, named for St. Peter Claver, held classes primarily at night and folded in the early 1940s. Other colleges included Methodist Episcopal College at Boley, Flipper-Key-Davis University in Tullahassee, Creek-Seminole College, which started at Boley, Sango Baptist College in Muskogee, and Oklahoma Baptist College for Girls in Sapulpa. This list may not be complete, and the grade level of education is unknown in most instances.

Another aspect of African-American higher education was the process by which black teachers acquired teaching certificates. Every summer, in differing locations there were county “normal” schools or conferences that had the authority to issue or renew certificates for successfully completed work. In 1916 the Oklahoma Legislature ended this practice and, starting the next year, most African American teachers had to travel to the college at Langston. Some of these smaller colleges tried to relieve that burden by offering appropriate courses.”

Maude J. Brockway and Drusilla Dunjee Houston were movers-and-shakers, not only in Oklahoma City, but Oklahoma and bordering states, as well. Before being involved with the Baptist College, both women fought for rights, equality, and education for people of color.

Maude J. Brockway, born in 1876, from Arkansas, attended the Arkadelphia Presbyterian Academy, a school district to educate the children of former slaves. She enrolled at Arkansas Baptist College before she moved to Oklahoma City just after statehood. Brockway became active in the Black Clubwomen’s Movement. By 1910, she became one of the founders of Oklahoma Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs.

Through her studies and activism, Brockway developed an institution through the Baptist Convention. She became Sapulpa’s Oklahoma Baptist College superintendent until 1918 or 1919. The principal under her wing was Drusilla Dunjee Houston; Drusilla would become superintendent after her.

Drusilla Dunjee Houston, born in 1876, from West Virginia. The family came to Oklahoma in 1892. Although she did not attend college, Houston pursued a teaching career. From 1892 to 1899, she was a kindergarten teacher in Oklahoma City. She became disheartened with the education system for black students. She opened her own school, McAlester Seminary for Girls, for twelve years.

In 1917, she began working in Sapulpa in the new Baptist College. Although the principal, she remained an educator. It offered two-year teaching degrees above a high school education, as well as, domestic science in sewing, cooking, laundering, housekeeping, and sanitation*.

*Note: Oklahoma Historical Society stated it was a two-year teaching degree, however, in the Black Dispatch (a black-owned Oklahoma City newspaper) stated it “offered a four year academic course, domestic science, domestic art, music, beauty culture, mission study, and commercial training.

Although the newspapers said little as to why the school closed, in 1922, due to financial instability, it would combine with another institution. Between Sapulpa and Muskogee schools, only one location could be kept operating. After leaving Sapulpa, both Maude J. Brockway and Drusilla Dunjee Houston continued their passion in Oklahoma City.

Brockway participated in various organizations such as Order of the Eastern Star, Oklahoma Women’s Baptist State Convention, Oklahoma Mission Society Federation, becoming president of this organization from 1925-1950. Brockway Community Center, Oklahoma City, was headquarters to provide services to young Black women and children, improve the quality of life in local Black neighborhoods, and advocate for racial equality. “Brockway died on October 24, 1959 in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, while attending the state convention of the Women’s Auxiliary of the state Baptist Convention. Soon after making her address to the assembly, she had a heart attack and died. The Oklahoma Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs honored her with a memorial service during the 50th Anniversary celebrations of the organization’s founding. Brockway’s daughter, Inez Brockway Brewer became an active clubwoman and teacher. In 1968, the Brockway Community Center moved to 1440 North Everest Avenue and in 2019,it was nominated for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places listings in Oklahoma County, Oklahoma. The center, named in Brockway’s honor, is the only extant structure affiliated with the Black Clubwoman’s Movement.”

Houston, similarly, continued to work in Oklahoma City for organizations such as YWCA, Red Cross, and NAACP. She continued to work with her brother, Roscoe Dunjee, at the Oklahoma Black Dispatch newspaper. “The earliest African-American woman to write a multivolume study of ancient Africa, she is best known for her classic American historical text, Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire. Written over a twenty-five-year period, the book was published in 1926 and reprinted in 1986 (as Wonderful Ethiopians; it was written to correct distortions in the historical record of ancient African people and their descendants worldwide). Houston had two children, Florence and another unnamed daughter who died earlier. Price Houston, her husband, died in 1931. Like her mother, Drusilla suffered for years from tuberculosis. Drusilla Dunjee Houston died in Phoenix, Arizona, on February 8, 1941. In keeping with her deep faith, her gravestone bears the words ‘To Die Is To Gain.’”

(Creek County Republican, December 5, 1913, January 16, 1914, June 19, 1914, July 24, 1914; October 8, 1915; Black Dispatch, December 28, 1917, June 28, 1918, September 14, 1922, October 30, 1959; Sapulpa Herald, December 22, 1968; Sapulpa City Directory, 1916 and 1922; Oklahoma Historical Society)