Rachel Whitney

Curator, Sapulpa Historical Museum

Sapulpa, Indian Territory (I.T.), was incorporated in 1898. Although the enslaved people had been freed following the Civil War, the United States government enacted a “separate but equal” system of racial discrimination and segregation. In the city of Sapulpa, which was organized under the Curtis Act (as part of Dawes Act— it resulted in the break-up of tribal governments and communal lands in I.T.) Whites were allowed to purchase town lots, but under this Act, there was no mention of segregation. Some city founders held opposition to permitting the black community, necessary to the businessmen for menial services, to live among them. This formed the beginnings of that division of the city which segregates the people of color in Sapulpa.

Sapulpa’s black community had established its own businesses, clubs, and patrons due to segregation laws in town. In so doing, Negro Chamber of Commerce, black-owned hotels, restaurants, grocery stores, and other businesses developed in the community.

On May 27th, 1942, the Sapulpa Negro Chamber of Commerce began its organization. A. J. McAlpin, president, agreed the purpose of the new group is “to improve general living conditions for the colored residents of this city.” The first members included Claude Bagsby, vice president, A.R. Hawkins, secretary; Frank Hollier, treasurer; Ed German, chaplain.

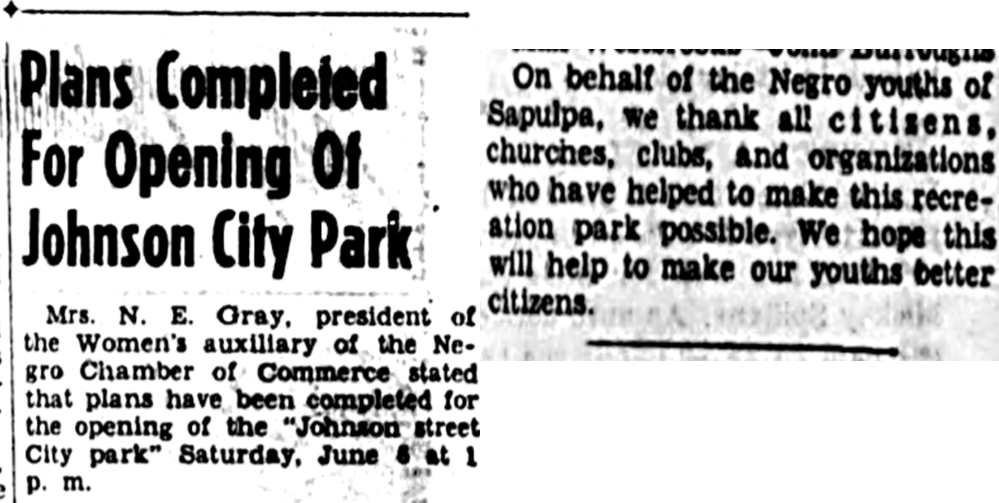

Women’s Auxiliary Negro Chamber of Commerce began just after the war, joining the efforts to strengthen the community. These organizations tackled projects such as war bond drives, paving the roads, and building a community park. The park had a “wading pool, installed 100 Chinese Elms, 27 evergreens and a lane of irises,” and it had a ballpark that would be downgraded to make room.

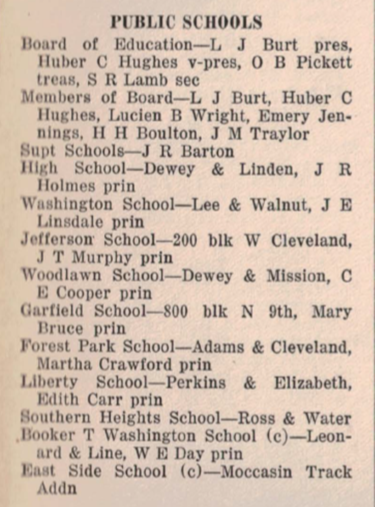

Information can often be found not only in newspapers but in City Directories. City Directories are similar to phonebooks; however, City Directories list everyone even if that person did not have a phone number. City Directories also listed your name, (spouse’s name), your job title and its location, your residential address, and your phone number (if you had one). These books also included an abbreviations page to help identify the meaning of “carp” for carpenter, and “mgr” for manager, and “wid” for widow. In the older Hoffine’s and Polk’s City Directories, mainly pre-1960s, when “(c)” appears next to a name, the mark means “colored” to indicate people of color.

Segregation of churches for Sapulpa began at statehood. The first mention of segregated establishments appears in the 1907 City Directory with two First Baptist Churches: “First Baptist Church—nw corner Elm and Thompson, Pastor Rev J.H. DeLano” and “First Baptist Church (c)—corner Lincoln and Cedar, Pastor Rev J.A. Murray”. By 1911, Sapulpa’s City Directories listed “colored denominations” separately. As families grew and added to the community, churches, funeral homes, and schools became more and more needed.

Embalmers, undertakers, and funeral directors were often the ambulance and medical care personnel. The “Sapulpa Funeral Home (c)” was listed in the City Directory in 1920. The following year, the “Glass Funeral Home (c)” was operated by Edward Glass (then later by his wife Lula Glass). By 1938, the funeral home was the “Dyer Funeral Home (c)” (also known as Dyer-Paterson Funeral Home), and it operated until 1975.

Hoffine’s and Polk’s City Directories also listed (c) schools but not organizations, such as the Negro Chamber of Commerce. It is uncertain why, but the City Directories were not always reliable for the black community. These City Directories from 1914 to 1960 listed “Booker T. Washington High School (c)” as having a different address nearly every other year.

As stated earlier, City Directories’ information for the black community was limited or vague. The information gathered for the City Directories are similar to gathering the information for the Census; either from people turning in the information of their household and business or Census-like workers conducting a survey. Either way, the City Directories rarely listed a person of color’s job title or their place of business.

Most information gathered from the City Directories lists “lab” or laborer for a person of color. The workers operated facilities such as Frisco railroad, Sapulpa Cotton Compress, and rooms and laundry. Others were cooks and dishwashers for local restaurants and hotels, such as West Virginia Café and Hotel Ripley.

Within the City Directories’ abbreviations used “prop” for proprietor. Proprietor means the owner of a business or a holder of the property. Black-owned businesses were not uncommon throughout Sapulpa’s history. Edward Glass became the proud proprietor of the People’s Drug Store and GW Hotel at 204-206 N Johannes in 1914. He would later own the Glass Funeral Home.

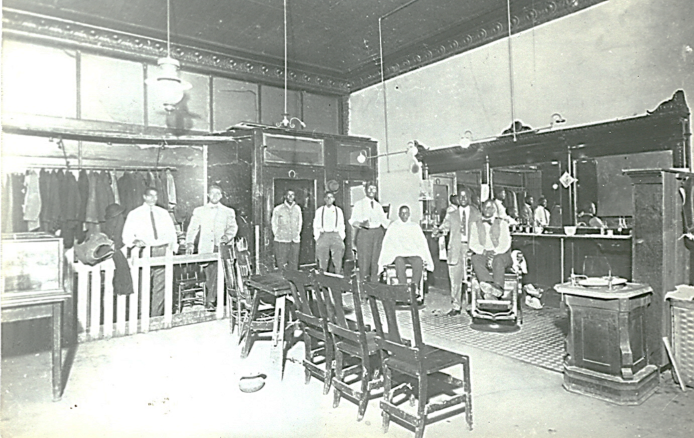

Johnson & Hodo, a black-owned business, at 411 E Hobson Ave. In 1914, this was a barbershop and a cleaners & pressers owned by Thomas R. Johnson and John S. Hodo. Johnson, prior to being the owner, had been the janitor at the Post Office. Then by 1916, Johnson was the only proprietor and called the store Johnson Cleaners & Pressers. By 1918, it moved to 204 N Johannes.

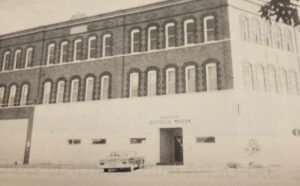

The Clayton Building was built in 1918 in the heart of downtown Sapulpa with royalty money from the discovery of oil in 1905 on the Ida Glenn farm (present-day Glenpool in Tulsa County). “It was constructed in 1917-18 by Manhattan Construction Co. with two architects Popkin and Larry Rooney. Original owners were Ernest [William McKinley] Clayton and his sister Bessie, Creek (Black) Freedmen who used their profits from the Glenn Pool to finance the project.” The man who directed the construction of the building and managed its initial operation was Henry Lowrance, born to a black slave family in 1864. “As guardian of his step-grandson, William McKinley Clayton and his granddaughter Bess Clayton Fondreaux [were] heirs to the large Clayton Estate.” Lowrance was “instrumental in erecting one of the largest business buildings in Sapulpa.”

“Lee Birmingham was a master of BBQ and the quintessential example of entrepreneurship. In 1947, Lee rented a small building on Hickory Street next to the railroad tracks to open “Lee’s Hickory BBQ.” After several years there, Lee left that building for reasons unknown and started cooking from his backyard at 507 E. Hobson. He built a horseshoe-shaped fire pit out of brick, stone, and lined it with concrete, put a grate on top, and used a piece of metal as a roof to keep out the rain. Lewis Bruner remembers sitting in Lee’s black 1947 Pontiac and selling BBQ from the car. Lee and Lewis would take the meat right off the fire, wrap it up in wax paper, then newspaper, and sell the steaming meat to the eagerly waiting customers lined up in the alley behind the house. Lee Birmingham had both the Hobson St. and the Johnson St. locations in operation at the same time. He planned a third location on Line Street, but sadly, the May 5, 1960 tornado ended those plans. Lewis had ended his shift and had gone across the street to play pool. Around 6 p.m., Lewis heard a sound he thought was a freight train. He thought a train had jumped the tracks nearby. The tornado took the second story off the building, but Lewis and the other occupants who had taken shelter under the pool table, survived the deadly storm, unscathed. Lewis looked across the street and saw that Lee’s BBQ building was “gone.” He and others rushed across the street. Lee Birmingham was buried under a pile of rubble that had been a wall, underneath a table. They took him to Bartlett Memorial Hospital (now St. John Sapulpa) in Lee’s 1956 Ford station wagon. Tragically, Lee did not survive.”

“Holeman “Dago” Pearce began a shoe-shine business in 1950. After 32 years of working shoe-shine in the train depot and a barbershop, Dago finally owned his own business. The establishment was in a small section of City Drug (now Brown Insurance) facing Main Street. From dawn to dusk 5-days-a-week, Dago was ready to shine your shoes and tell of the latest happenings in this fair city. Doctors, lawyers, judges, business owners, and yes a few shady characters, had their shoes shined at Dago’s. Dago always had a smile on his face and treated everyone like royalty. He was always known as the Mayor of Main Street, a few years ago, The Mayor and City Council issued a proclamation naming him “the official Mayor of Main Street”. He retired in 1992 and passed away in December of 1993. Another in a long line of mom-and-pop business that gave very personal service and brightened everyone’s day.”

(Sapulpa Herald, May 28, 1942, May 29, 1942, June 25, 1942, January 29, 1946, October 6, 1949, June 3, 1953; Tulsa Star, June 20, 1914; Sapulpa Times: May 2, 2016, October 30, 2018, February 18, 2019; “Picturing Our Heritage: The African-American Community”—an historic photographic exhibit; (Hoffine’s and Polk’s) Sapulpa City Directory 1907, 1911, 1920-1975).