Publisher’s note: Horse passed away in June of 2020. We’re republishing his story here to honor his memory.

—

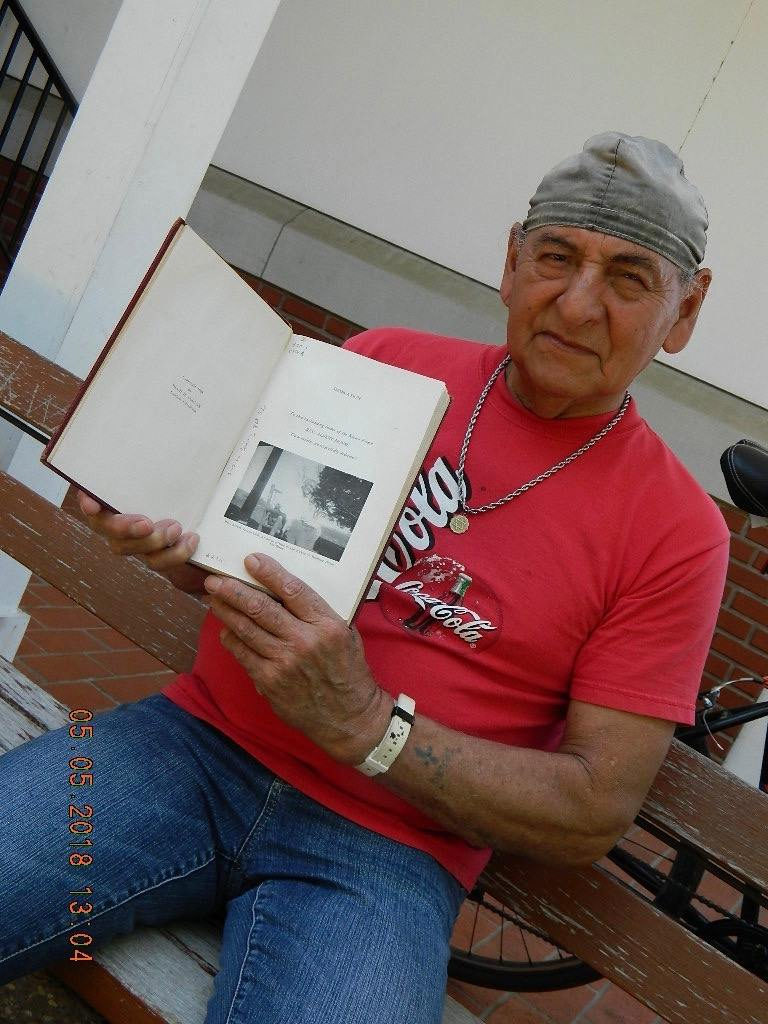

“It’s all in the book.” That’s a true statement in more ways than one for Native American Dewey Horse of Sapulpa. Horse who just turned 70 is a Kiowa/Creek Indian. He is the great-grandson of famous Kiowa Indian scout Hunting Horse.

Dewey knows two books quite well. In a sense both are sacred. One is the Bible. It is “holy,” Horse says. The other is “The Kiowa Indians, Their History & Life Stories.” He does not put the two on the same level, but both are extra important to Horse, and to the Kiowa Tribe. The latter, a 1958 definitive work by Hugh D. Corwin of Lawton, cites Dewey’s grandfather, the Rev. Albert Horse (son of Hunting Horse) as one of its main sources. In fact, the book is dedicated to the Methodist and Kiowa leader. Unless Dewey Horse is leading one of his Bible studies when he says “it’s all in the book,” he is talking about Corwin’s work as it pertains to the life of the famous scout, his family and tribe.

Dewey Horse likes to read and consequently spends a lot of time at the Bartlett-Carnegie Sapulpa Public Library to where he rides his bicycle to pursue the Kiowa history as well as point other family members and Native Americans to the book.

Recently, when telling his story to Judge Rick Woolery — that of kinship to the famous, first warrior then scout, Hunting Horse, the judge became fascinated. A friendship was formed and Woolery ended up gifting a new copy of the book to Horse.

“That he would do that, was really special,” Horse said as his eyes welled up during a recent interview at the library, “but when he called me his friend, that was really meaningful.”

Horse hopes others will check out the library book. It is quite a history. Not much had been written about the Kiowa people before the publication of the book in the 1950s. There were letters and documents, many in the hands of Dewey’s grandfather Albert.

“I was his favorite,” Dewey recalls of his grandpa. “He invested in me. I remember us walking and talking around the old home place,” Dewey said. “When you grow up you and those that follow you will know the story of your family and tribe,” the older Horse told his grandson referring to the book he helped compile. The old homesite is still there at Meers, Okla., near Mt. Scott and the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge. The 80-acre (part of an original 160-ace set-aside) farm is where Hunting Horse resided and where generations of his family would be born and reared.

Hunting Horse lived to be 106. Dewey Horse was around five when the old scout died in 1952. He and his younger sister, Debra Ann, both remember the aged man who still spoke his native Kiowa tongue when he passed.

Hunting Horses’s big rocking chair (Albert is shown seated in it in the book) was rather unique. Made of cedar and buffalo hide, it is now displayed in the museum at Fort Sill. Hunting Horse is buried at Fort Sill, but a birth site marker for Albert can be found at the original homesite.

Albert became a Christian and under the ministry of Dr. Dewey Etchison was ordained a Methodist minister.

“They were close,” Horse said. “I was named Dewey, my first name, after the Rev. Etchison at my grandpa’s request.”

Albert rose in rank and respect as a leader in the Methodist Church as well as the tribe. Another son of Hunting Horse, Cecil, also was a minister. His daughter, Mamie Ike Johnny, was Hunting Horse’s caregiver in the final years on the Horse allotment.

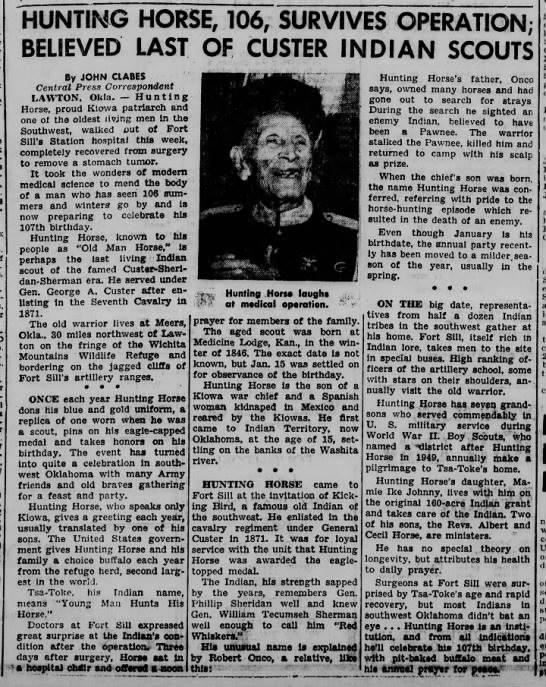

As for the famous scout (then referred to as “Old Man Horse”), newspaper accounts reported at the time of his death, that Hunting Horse was believed to be the last living Indian scout of the famed Custer-Sheridan-Sherman era. He served under Gen. George A. Custer after enlisting in the Seventh Cavalry in 1871. Custer had requested Hunting Horse go with him on his northern campaign. Arrangements didn’t materialize else Hunting Horse likely would have died with Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

Tsain-Taunkee (Tsa-Toke) or Hunting Horse, as the white people came to know him, was born in the Southwestern part of Kansas, so records Corwin’s book. The tribe drifted to Texas after buffalo were diminished in Kansas.

According to the last big newspaper feature on Hunting Horse, the government gifted a prime buffalo to Hunting horse annually. He was preparing for his 107th birthday party where he planned to have pit-baked buffalo meat and offer his annual prayer for peace. He attributed his longevity to daily prayer and proper attitude toward others.

His Favorite

“I was his favorite,” Dewey recalls of his grandpa. “He invested in me. I remember us walking and talking around the old home place,” Dewey said. “When you grow up you and those that follow you will know the story of your family and tribe,” the older Horse told his grandson referring to the book he helped compile. The old homesite is still there at Meers, Okla., near Mt. Scott and the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge. The 80-acre (part of an original 160-ace set-aside) farm is where Hunting Horse resided and where generations of his family would be born and reared.

Hunting Horse lived to be 106. Dewey Horse was around five when the old scout died in 1952. He and his younger sister, Debra Ann, both remember the aged man who still spoke his native Kiowa tongue when he passed.

Hunting Horses’s big rocking chair (Albert is shown seated in it in the book) was rather unique. Made of cedar and buffalo hide, it is now displayed in the museum at Fort Sill. Hunting Horse is buried at Fort Sill, but a birth site marker for Albert can be found at the original homesite.

Albert became a Christian and under the ministry of Dr. Dewey Etchison was ordained a Methodist minister.

“They were close,” Horse said. “I was named Dewey, my first name, after the Rev. Etchison at my grandpa’s request.”

Albert rose in rank and respect as a leader in the Methodist Church as well as the tribe. Another son of Hunting Horse, Cecil, also was a minister. His daughter, Mamie Ike Johnny, was Hunting Horse’s caregiver in the final years on the Horse allotment.

As for the famous scout (then referred to as “Old Man Horse”), newspaper accounts reported at the time of his death, that Hunting Horse was believed to be the last living Indian scout of the famed Custer-Sheridan-Sherman era. He served under Gen. George A. Custer after enlisting in the Seventh Cavalry in 1871. Custer had requested Hunting Horse go with him on his northern campaign. Arrangements didn’t materialize else Hunting Horse likely would have died with Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

Tsain-Taunkee (Tsa-Toke) or Hunting Horse, as the white people came to know him, was born in the Southwestern part of Kansas, so records Corwin’s book. The tribe drifted to Texas after buffalo were diminished in Kansas.

According to the last big newspaper feature on Hunting Horse, the government gifted a prime buffalo to Hunting horse annually. He was preparing for his 107th birthday party where he planned to have pit-baked buffalo meat and offer his annual prayer for peace. He attributed his longevity to daily prayer and proper attitude toward others.

Hunting Horse, Dewey Horse’s great-grandfather, lived to be 106 and was planning his 107th birthday when he passed.

Some of that and the influence of Albert Horse evidently “rubbed off on me,” said Dewey Horse, who at one time felt called to become a minister like Albert. He was 40 before he actually became a Christian however. By his own testimony until then he supposed his grandfather had secured his place in the family of faith.

“I didn’t know it,” he said, “but I was running. “I think I thought I was OK because of grandfather’s faith. It doesn’t work that way.”

Asked about injustices and plights of Native Americans, Horse is quick to point out that following Christ is the answer to all of life’s problems regardless of race, culture or background.

Not the White Man’s religion

“Christianity is not the ‘white man’s religion,'” he said. “It is a religion of forgiveness…all need forgiven, and all need to forgive.” His recommendation: “Avoid becoming entrapped in unforgiveness, and don’t hang around those with an unforgiving spirit.”

Following his grandfather’s footsteps into the Methodist clergy proved to be more requirements, schooling and training than Dewey could muster or find biblical mandates for at mid-age, but he did become a lay-leader; has preached on occasion and still loves to lead and do Bible studies.

Dewey, a welder for most of his life works today part-time at Victory Cafe (ironically on ‘Dewey’ Ave.) in downtown Sapulpa where “you can find some of the best food anywhere.” Wanting to plug the restaurant in anything written about him he said “be sure and tell them about Terri’s meatloaf.” (Terri is the owner and his boss.) He also wanted to plug KXOJ Christian radio station at 94.1FM in Tulsa.

Horse admits he is not the “horse”man like his predecessors but he still loves the out-of-doors and he does ride a bike. (Physical exercise on a bicycle and spiritual exercise from the Bible, a dually-good health practice, he believes.) He hunts some. His father Richard was an avid hunter and fisherman.

Dewey has family — a living brother, sister, children, grandchildren, nieces, nephews, cousins and tribal members giving over to the big annual family reunion each year.

He hopes to ever encourage all of them to be thorough in the knowledge of their heritage. Its all in the book.

By the way, here are some excerpts from the copyrighted work:

Pea-Lame, the father of Hunting Horse was born in the Black Hills of South Dakota before the year 1800, possibly as early as 1790. When he was a small boy both he and his mother were captured by the Osages. Pea-Lame had an enormous scar across his back and he received it in this way; Shortly after he and his mother became prisoners of the Osages they were given some meat to eat and a knife to cut it with. The knife was very dull and had the point broken off. The mother of Pea-Lame taunted the Osages with the giving her a dull and broken knife to eat with. She said “I’ll fool you anyway. I’ll kill my son and myself with this broken knife and you won’t have us for slaves”. As she said this she slashed Pea-Lame across the back with all her strength, but before she could get a second stroke the Osages shot and killed her. Pea-Lame lived, but bore the scar all his life.

<h3>Giving up their horses</h3>

When Hunting Horse was some 9 or 10 years old, his people were still roaming the plains, Chief Kicking Bird persuaded many of them to come to the Agency and settle there. A good many of the Kiowas realized it was best for them to surrender to the Army and man’s ways. This meant giving up their horses, in most cases, and this the Kiowas were very reluctant to do. They preferred their wild ways to the way Kicking Bird was advocating.

The Government used several plans in trying to get the Plains Indians to come in and settle in peace. One was the sending of wagon trains of food and presents to give, as an inducement to surrender. The big drawback to this plan was that the food sent by the peace commissioner was not wha the Indians would eat. Sides of cured bacon, the Indians were told by some of their people, who opposed surrender, was elephant meat and that it was poison and would kill them if eaten. Consequently it was thrown away or burned. It made a big fire. Rice, they called “dried Mmaggots” and it was not fit to eat. Flour was lots of fun to throw around and get it on your face and hands to make you white. Coffee they soon learned to use, and sugar was the most popular of all. The clothing given was of little use as the Indians at first refused to wear white mans’ clothes.

When these wagon trains of supplies, guarded by soldiers, approached the Indian camp, the Chiefs sent the camp caller to tell everyone to assemble. The people would all come and sit in a circle on the ground and then the supplies would be unloaded and distributed. On one occasion the army people brought to Hunting Horse’s band some watermelons and sugar came or sorghum stalks, to shot the Indians what could be grown as food and as an inducement to get them to settle at the Agency. The soldiers showed them how to peel and chew the joints of cane and get the juice, spitting out the pulp. Afterwards they cut the watermelons and each Indian had a taste. That was the end of the desire for wild life by Hunting Horse. One night he said to this mother, Sale-Beal, “Ma Ma, let’s go to the agency, to the good country and settle down”. Apparently his mother agreed, for in a few days they joined a group going in, some on horseback and some on foot.

After Pea-Lame died his family were poor and they had no horses so they had to travel on foot. After many days travelling, they came to a place on Cache Creek between where Apache and Fort Sill are now located. There they bottom lands were being cultivated and crops raised by the Agency Indians. The man in charge of the group said “look yonder at the fields and the crops they grow”. “That is where the watermelons and cane grows”. Hunting Horse and the other boys started running for the fields. Hunting Horse had a knife of which he was very proud, and he outran the other boys reaching the field first and began to use his knife to cut down and peel cornstalks. He chewed up the cornstalk, thinking it was ate and swallowed the juice. It probably didn’t taste just like cane but he was too excited to notice the difference. He filled himself up with cornstalk juice. Then the other boys yelled that they found watermelons so he came running and found what he thought was a melon and cut and ate it. It was a pumpkin but he hardly noticed the difference. In a very short time he was full of pumpkin and cornstalk juice. In face he had more than he wanted. He began to hurt and to be sick. His mother heated a flat rock and had him hold it on his stomach to draw the pain out. No doubt after this experience he was more cautious about the new food the white men were teaching them to eat.

Settling at Fort Sill

Hunting Horse could not recall the year he and his mother and sister settled near Fort Sill. For some time peace reigned and he soon became a young man. He remembered that he was guide for General Custer and made trips to the great plains for him to contact the wild tribes there. We know General Custer was at Fort Sill for a few months in 1869, but there were troops there all the time and the friendly Indians helped toward the ways of peace by guiding the troops over the country. Hunting Horse often told his children that General Custer wanted him to go with him when he left Fort Sill, but that he could not go because he had been ordered to go to the great plains in the West to talk to the wild Indians. He said, had he gone North with Custer, he would no doubt have been killed with him in the battle of the Little Bighorn.

In 1869 Col. Albert Gallatin Boone, a grandson of Daniel Boone, was appointed Agent for the Kiowa and other Plains Indians. He moved the Agency to the newly established Camp Wichita on Medicine Bluff Creek. Shortly after this, Fort Sill was laid out under plans of General Sheridan on a plateau of ground about one half mile southeast of old Camp Wichita.

And of interest:

We have used the headline “A Man Named Horse.” The movie’s title was “A Man Called Horse.” It was a 1970 American Western film starring Richard Harris and directed by Elliot Silverstein based on the short story “A Man Called Horse” by the Western writer Dorothy M. Johnson, first published in 1950 in Collier’s magazine and again in 1968 in Johnson’s book Indian Country. The basic story was used in a 1958 episode of the TV show Wagon Train titled “A Man Called Horse”.